laser light - puppetry - crop top

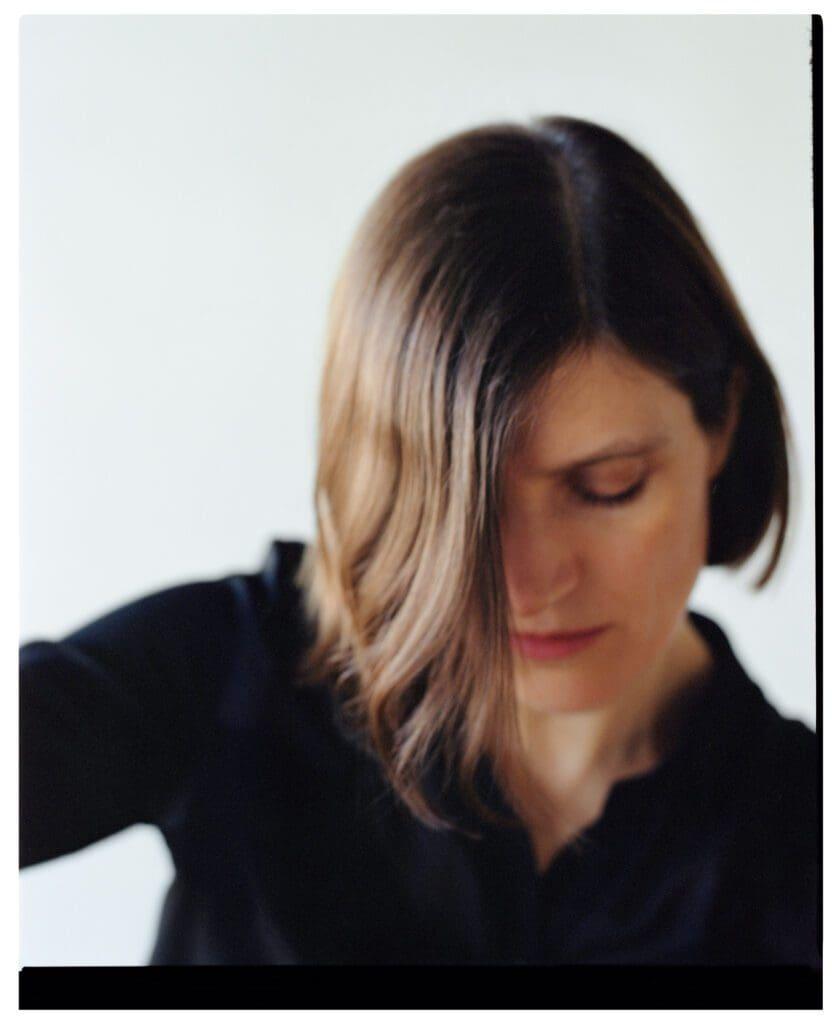

A conversation with Gisèle Vienne

On Friday November 21, we met up with Gisèle Vienne, to talk about Extra Life, life in general, and the current state of the world. “We” are Jessica Gysel, coordinator for Team Publiek at Kaaitheater, and Lucy McKenzie, a Brussels based visual artist who’s been following Gisèle’s work for a long time and, as a matter of fact, introduced Jessica to her work long before she started working at Kaaitheater.

Both Gisèle and Lucy have a practice that crosses different disciplines; both have background in the ‘artisanat’ and share a love for puppetry, circus, playgrounds and fairs. They are interested in balancing the fine line between the mundane and arcane – all while merging their art with politics.

Lucy: Coming out of your piece yesterday, I was once again reduced to tears. And then, I saw other people that looked a bit like they had just gone to see a tennis match or something. And I just thought, Wait, did we see the same thing? But of course, it touches people in different ways. The fact that this is completely contained within the work is such an act of resistance.

Gisèle: I'm happy to hear that, because I really tried to be accurate. I mean, of course, there were a lot of feelings, sensations, and intuition, but there was also a lot of listening, [connecting with] personal experiences.

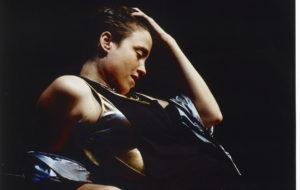

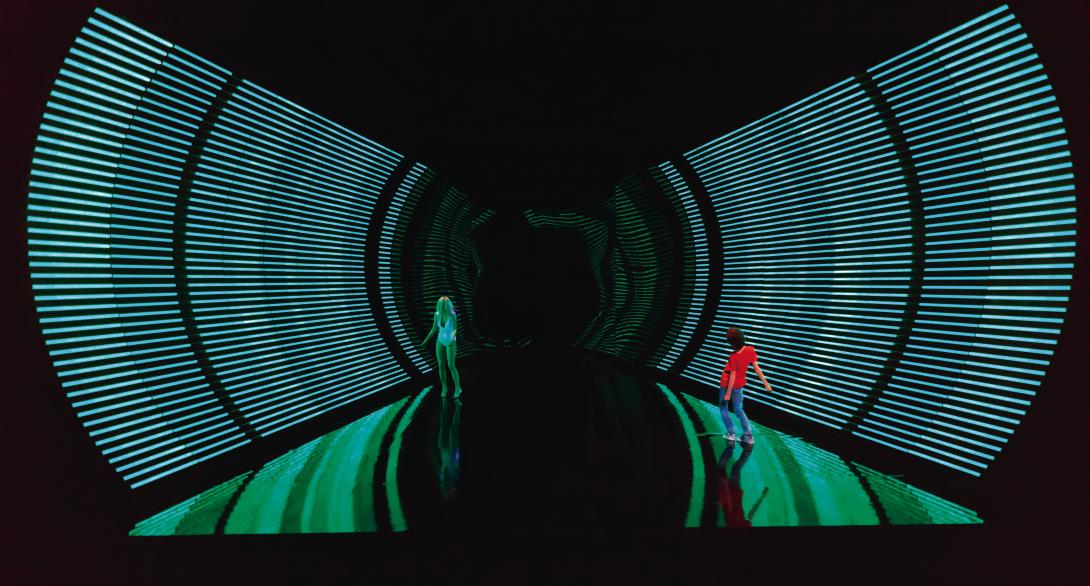

Jessica: What I really liked yesterday was the fact that the performance felt like a trip. Just like a moment spread out in two hours and in different layers, different parallel time zones or something. So, I was wondering if you can talk about that more, because it really touched me, and it felt like I was with the actors or the performance on this trip, you know?

Gisèle: For me, the core question is a perceptive frame. What are our perceptive frames? How do they move in space and time? What do they say about the society we're in? How can we act on them, to change things structurally? That's something we can work on that is political. I think this is crucial in the arts or in any type of visual work. How can we create other languages that make us see, hear differently, or perceive what we usually aren’t able to do? But it's not easy to create these forms. And also, there is a logic. One logic I've tried to investigate is that of thinking processes and emotions. What is influencing your perception and how: if you're very afraid, or if you're in love, or whatever that means to you, if you are joyful or if you're very depressed, you wouldn't see the same thing in the space. [I] wouldn't mix the sound the same way. I mean, [I] could, but it would be really different. That's very vivid for me, because I'm very much into somatic practice. I work a lot with the fascia, I meditate. I imagine a strategy to create some physical moves. But I also practice self-defense. That activates more things like, where are the exits? How can you move the fastest? It’s a totally different way of imagining.

Lucy: It's also the complete opposite of the current phenomenon of marrying right-wing politics with wellness. This is politicizing the parts of what could be considered some kind of wellness or self-care, this like bodily awareness, but it's for political openness, rather than a system of fear, control and consumerism…

Gisèle: You can make a huge business out of somatic practice because they're really amazing praxes. They are very big in neoliberal circles because they do increase efficiency. They can totally be misused. There are a lot of assholes. You could make so much money if you wanted to…

Jessica: Jumping from here, can you say something about the group process, and the bodily practices related to that? Because for instance, you have three people playing two characters.

Gisèle: Performing arts is about gathering people – the social cohesion that this gathering creates is something very important. And then, of course, you want to be very respectful of this effort. The contract with the audience is to try to create an experience that can be meaningful, that can create self-reflection, with room for spirituality and emotions. It’s a different position than the entertainment industry. That also has its role – and it’s needed - but it's more in tune with neoliberalism. It’s like: ‘I'm selling you a comedy, and the contract is you're gonna laugh, or it's gonna be an erotic thing, so you're gonna be excited, or it's gonna be a horror thing, or it's gonna be a romance, so you're gonna cry. So, there is a very specific contract. We don't have this type of contract.

The logic of neoliberalism and fascism is to destroy any critical space, any sensitive space for self-reflection. And it's not a budget question. It's an ideological question for sure. Their logic is to cut off affective bonds between people, isolate people, fucking up any affective links, friendship, love. So, I think it is already a type of resistance: to maintain, to develop, to fine tune these affective and social bonds. So that's where I think theatre can play a big role. I don't want to exaggerate it, but I think for me, the theatre is a structure of resistance. It's vital to have this ground floor so that there is a collectivity there. I work with amazing people and artists. It is a dialogue, and I love that. I think it's very exciting to have this specific way of communicating with people – an ongoing dialogue between my colleagues whom I love to talk to, to talk with. I'm orchestrating it. I'm art directing. But the performers are always co-authors... I'm very worried about making power structures illegible. Because even in a collective, there are power structures. So, for me, it's always safer to make them visible than to erase them. It's actually a perfect strategy for abuse -- making power relations invisible.

Lucy: Every actor stays who they are, every musician, and you make this third thing together, but it's never a denial of your subjectivity as an individual.

Gisèle: I think for me, [collaboration] is very important; it makes the work so much stronger when this individuality and subjectivity can really be there. There’s a lot of craftsmanship needed to create a work like that, and I don't have all the competencies, and neither do my colleagues. And we have [our own] specificities. I like this. I really love complementing competencies.

Lucy: The thing that I really respond to in your work is the tapping into a very arcane, human, kind of carnivalesque art making, to use puppets, to use this trompe l'oeil of bodies moving in a contradictory way. That for me, has roots in this other kind of history of human collectivity, which is like the fairground, the carnival. Whether you call it entertainment or expression, it comes from a more working class or mass culture. When you put the viewer in a position of being disconcerted because they're not sure what they're looking at or if something is real or not, that really opens the space for us, the viewers, and for you to deliver what you want to say. I just find that very interesting, that combination of a kind of high art, but really recognizable forms which tap into something more vernacular. I think it really gives your work a power. If I think about, say, Jeanne Dielman by Chantal Akerman: It's a work of radical feminism about a housewife. It's a combination of the deeply familiar and the disconcerting and the new, and those things that have that richness of a kind of relationship between polar points of view, they always give the viewer a space to kind of make their own relationship to it in a way, rather than top down, being told what to feel about something.

Gisele: I studied puppetry, I had friends who were going to film school or contemporary art school, and I was already very aware about how puppetry was considered so uncool. When I was a teenager, I loved Mike Kelly and Cindy Sherman. That's the puppetry I like. I’ve always been attracted to craftsmanship. I wanted to be in an atelier and build things. I like that. I love to do book binding, engraving, puppet-making. It's funny because the current museum exhibitions also use this type of resistance. It's just like there is this hierarchy of, you know, good taste, bad taste, high art, and for me, also in relation to humor, I think it’s very subversive. I love it. It makes me laugh and it fills me with joy.

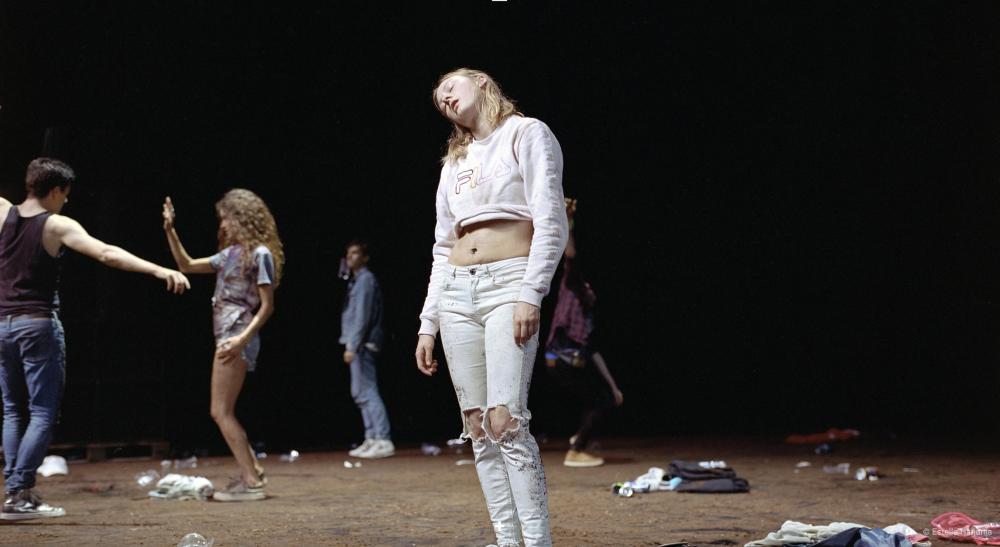

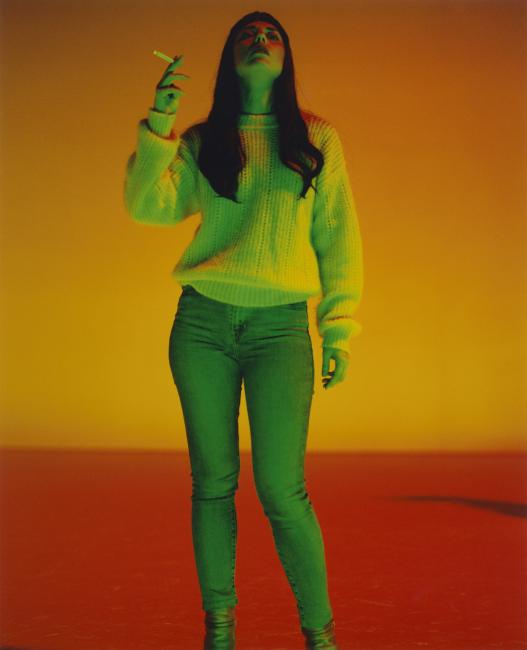

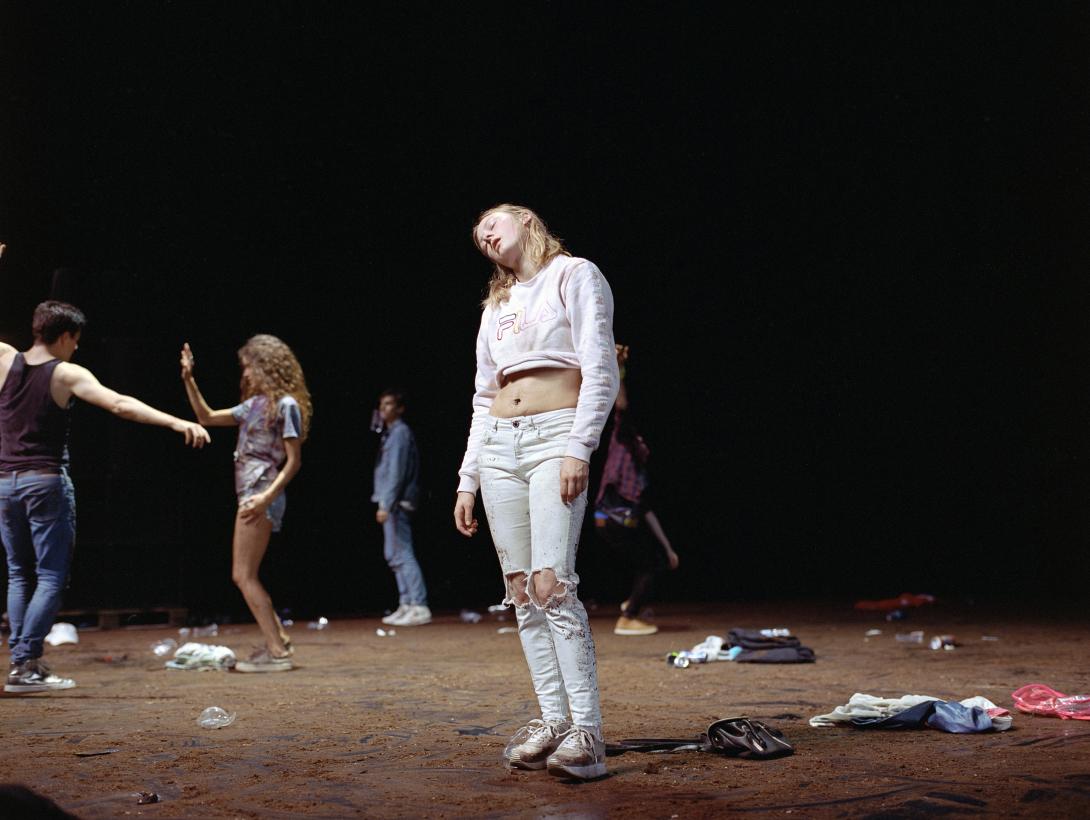

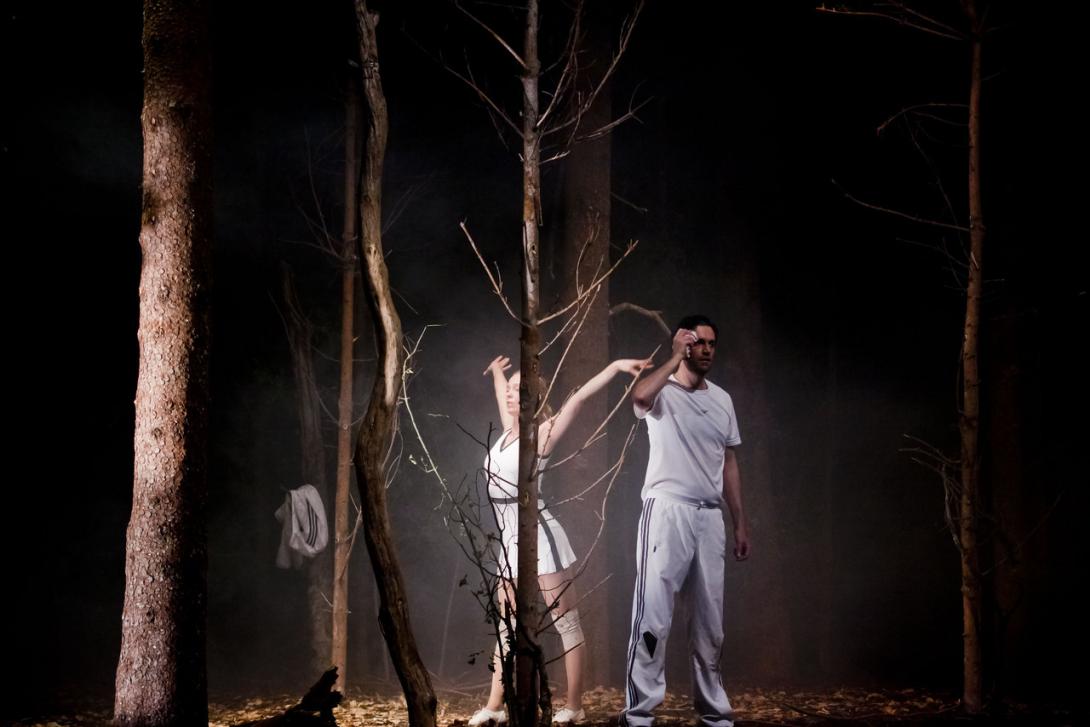

Actually, when I did my show This is how you will disappear in 2010 with Fujiko Nakaya... There is the forest made out of dry ice sculptures, and when Jonathan [Capdevielle] watches over it, [the viewer] thinks about the guy with his black suit on the top of the hill watching over the landscape. Everybody imagines that the guy would necessarily think about Nietzsche or whatever, not thinking about how his wife is cooking potato puree at home. I'm like, we have to see that, because that guy perhaps thinks, I'm gonna write a big essay, and I'm a genius, but I didn't do anything. But that's fine, because I'm already a pre genius without even doing anything. So, it’s very much because of this that I made this play. I loved it. I mean, I loved doing this - creating shows like that. But afterwards, I received all these Wagner and whatever opera offers. So, I thought I needed to work on shifting this. And that's why I created Crowd. I'm like, okay, the girl with a crop top and a pink string eating potato chips, she can think about Elsa Dorlin and Michel Foucault and Sara Ahmed, and she can be on the top of 21st Century philosophy more than the guy with his black suit on the top of the hill, you know. So, it's like, how do you create this epic and these steps into different codes of science; what is so called vulgar and cheap and stupid and low art and low medium. So, that's becoming a priority: laser light – puppetry – crop-top.

Jessica: Synthesizer sounds.

Gisèle: Puppetry is an amazing art. We both agree on it, but it’s literally discounted, like, I mean, worse than puppetry is pantomime! I was also thinking because last week I saw two amazing performances, one is ‘The present is not enough’ by Silvia Calderoni and Ilenia Caleo and ‘Weathering’ by Faye Driscoll. I've always been excited by carnival, but also by drag and cross-dressing. My mother used to make a lot of drawings of cross-dressers. I love Marlene Monteiro Freitas. Why wouldn’t so-called “exaggeration” just be super sincere? This “affected” way of performing is very sincere. It's just another way of being.

I mean we're very lucky, despite this ugly backlash, I think there was always this culture. But I think it's shifting. And I'm like, I'm seeing so many great, great performances and I think the performing arts field is probably [the way it is] because of the economy; the culture allows for a lot of humorous criticism.

Jessica: But at same time, I think outside of that, the violence is bigger than ever, you know, And I think it's very safe within the context of the theatre or the institution, to a certain extent as well. But then outside, something that's always on my mind is how to bridge that gap.

Gisèle: I’m not sure if you can bridge it. But now it’s just like a total, facial fascism - the normality of it - and I’m not sure if you can fill the gap. I mean, I'm not sure if we can understand each other. Why are they like, so obsessed with feminism and transpeople and anti-racism? It’s because we all achieved something actually much stronger than what we thought. It's not only my work or only your work, it's all our work together. I have no clue how to appraise it, but for sure it's happening. It's like tea, waiting to be infused. It does do something beyond the moment when people go to the theatre. Also, I’m living with Adèle [Haenel], who was on the flotilla. We feel like we're holding just a wooden stick in front of the Israeli army. But it's like, incredible how much we can do with our wooden stick when they have nuclear weapons and millions of drones. It's amazing. We cannot underestimate how much we can do with very small means.

Jessica: Can you talk a bit more about the September 2025 Gaza flotilla experience?

Gisèle: We were a team of three people. Of course, this is not my artistic work; it's my political work. I'm coordinating. And then there was a press agent who came for free because he was on a political mission too. And then there was a community manager. She came in for free as well. So, I was like, I'm directing it (smiles). We’re like pros, these little teams, it's incredible. Adèle went on the boat; there were all these hundreds of people on different boats. We wished they would arrive to Gaza, but we knew that it would be very unlikely to happen. So, the goal was media and political pressure, and we scored. So, you know, where is the defeat and the score? To see the discrepancy of tools [we had], and in front you have the US, the Israeli army, international fascism. It's like, I mean, Netanyahu had to talk about it, you can say it was disturbing on that level.

Jessica: Was your team also linked to the other people on the boat and the other boats? Because I imagine many people have these little cells …Greta Thunberg,…

Gisèle: The people on the boat have different roles. You have people who are scientists, teachers, whatever… Adèle is an actress, but she's also a movie star, so she's a public figure, so she has the capacity to mobilize media. So, that's our tool. It’s mobilizing media through the hook of Adèle. On top of it she's a very smart woman and very articulate. And she's trained. All these years of Cannes… She knows how to be intimidating. She has a long practice of political thinking, of philosophy, of geopolitics. So, these are all her competencies. Of course, we would occasionally do something with Rima Hassan or with Marlene Engelhorn. It’s really important to be very precise about what we can do, what our playground is. I think that's what I like in performing arts; we are also trained to work as a team with different craftsmen. And I think that's the same in militant activist work. For example, when Adèle went on the trial, we worked with a colleague who is an amazing makeup artist. The idea was not to do crazy things. We worked with systems of science, she's gonna go to the trial with this child rapist, and at that moment, we would not consider that her body will be read hundreds of times in the media. So, what do we want? What does she want to say? Her jacket, the shade of her lipstick, the movement of her hair, it does tell something… The shade of makeup is already a language in itself.

To go back to the perceptive frame. That's what I meant with the shifts: How can we move the spaces of desirability to make other things? And I know what we're doing. I mean, that's why I think it's far beyond ourselves. I know contemporary dance is a place of high desirability. I had all the big brands asking, all the big brands, we don't work for them. I don't give them anything.

Jessica: Maybe we lack courage. I think a lot of people are just afraid to stand up and say what they want. It's also that people are scared of the consequences.

Gisèle: There are consequences, but I think the more we are in solidarity, the less hardcore it will be. I mean, there are consequences. And the thing is, I always think, yeah, perhaps it's fucking up my career, but that's the price to pay. That's my dignity; my dignity is there. I mean, of course I would be desperate, but I'm like: Okay, if it gets there, it gets there. And so that's why, for example, my safety net is like, if I can't work as an artist, it's just a psychological safety net. Because I think now, I'm lucky. But I don't know, in two years, you know, if I don't get kicked out for ideological reasons, but I'm like, Oh, I have a degree in this. If I do one year of study, I can become a small schoolteacher.

Jessica: And you have a lot of other craftsmanship skills!