This is a piece where different worlds meet

an interview with Benjamin Vandewalle & HYOID

Benjamin Vandewalle has already made several performances and installations where he wants to stimulate the senses of his audience in a new way. This is also true in Journal d'un usager de l'espace, where the focus is on the auditory. Two singers from the contemporary ensemble HYOID move through the theatre building singing and dancing and take the audience with them, from the threshold by the doors through the foyer, into the auditorium. During their final rehearsal days, Vandewalle and the two HYOID members Fabienne Seveillac & Andreas Halling talk about the road they travelled with this piece.

Journal d’un usager de l’espace is based on the book Espèces d’espaces by the French author George Perec. Why did you decide to work with this book?

BENJAMIN VANDEWALLE: The piece has a long history: Fabienne and Andreas initially asked me to create a piece with them based on the Indianerlieder by Karlheinz Stockhausen but for various reasons, we ended up not working with these musical poems. One of them was that we did not have the authorisation to change or update anything scenically in the piece were we to perform it.

FABIENNE SEVEILLAC: Stockhausen has two widows. One of them was in favour of the project and the other one was against. It raised interesting questions about orthodoxy adaptation of vintage contemporary music.

At the same time, even if the music is great, it was a blessing in disguise. Indianerlieder was based on native American poems and is a really blatant example of cultural appropriation. The way it was done in the seventies was not very sensitive and is even harder to defend now.

In other words, you had to find a new starting point for the piece?

FS: Indeed. I suggested George Perec’s Espèces d’espaces. I think it is an amazing book! You cannot really say if it is a novel or an essay – you cannot put it in a genre. To my knowledge, it has only been adapted once before as a music piece, which is crazy because for many people, especially in visual arts and architecture it is really considered a master-piece. There are a lot of people who will tell you that book as influential to their work.

BV: With the Stockhausen proposition, there was already the idea of working with a sound choreography or placing sound in space. In that sense, Espèces d’espaces seemed like a good new lead.

Perec is known for his playful and creative approach of language. It that also reflected in the composition of the music and the choreography?

BV: Not so much, also we did not use that much text from the book. Perec was in particular an inspiration for the kind of approach towards space: looking at space in a very banal and “daily” approach, but with some radical shifts in perception.

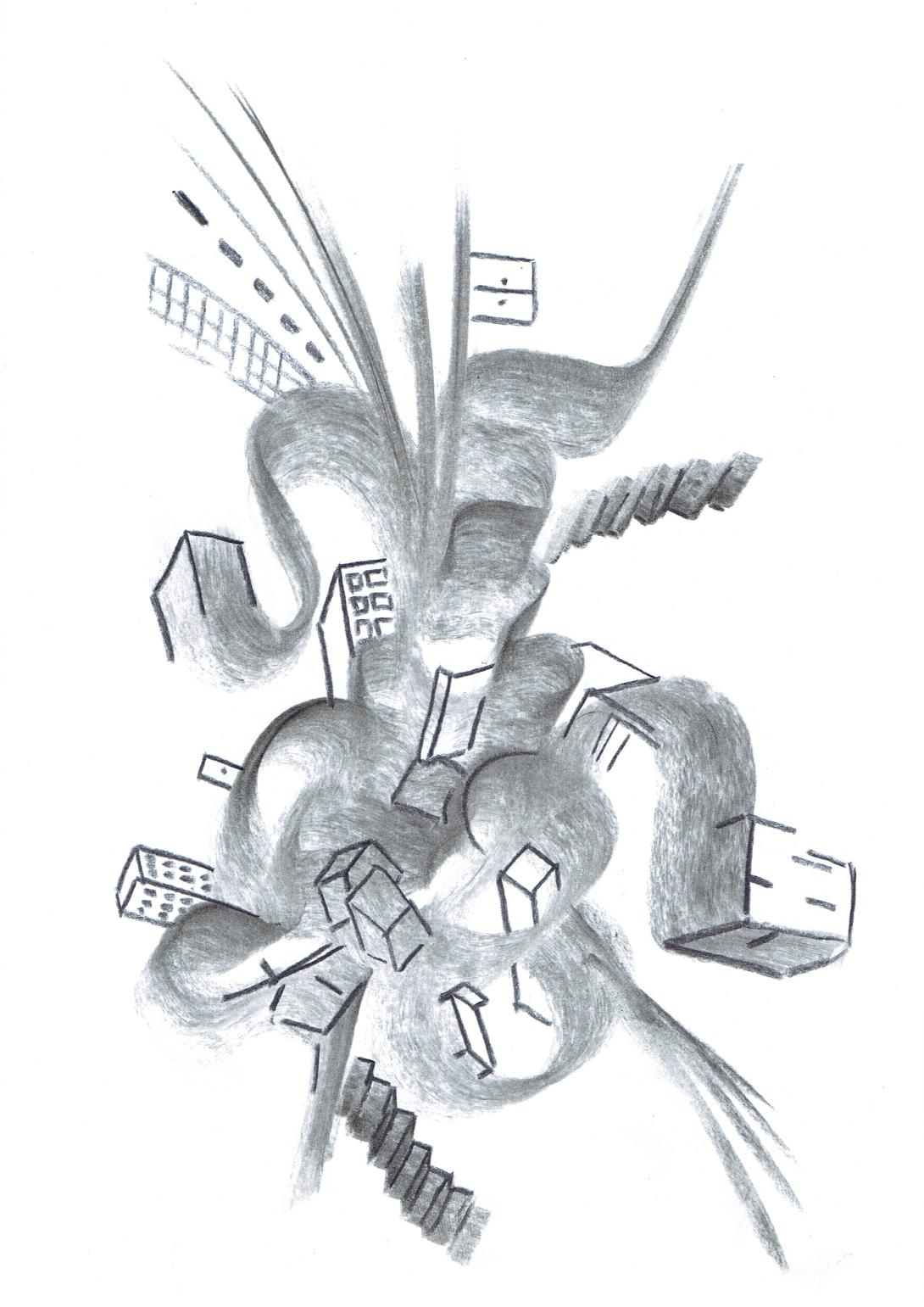

The dramaturgy of the book did play an important role in the structure of our piece. In his book, Perec starts with reflections of the personal space, the private space, the small space. Then he goes bigger and bigger towards the city, the world, until it becomes an abstract space in itself. In Journal, we do the opposite: we somehow start with the city, then go smaller to the foyer, and we finish in the more private, intimate space of the theatre hall. At the same time, in the theatre hall we offer reflections on the concept of space itself.

Senses are very important in your work, Benjamin. You played with the visual perception in, for example, Studio Cité or Birdwatching 4x4. You challenged the audience’s ears with Hear, and now again we can expect an immersive auditive experience. Can we see Journal as a next step in this exploration of the senses?

BV: Yes, it is definitely a continuation of a concept that came from Hear, which was also a sound choreography. Now, the word ‘sound sculpture’ is also present: how to install a sculpture that is alive and sculpted out of sound and moving bodies. I am becoming more and more fascinated with sound and hearing whereas as a choreographer/dancer, I was predominantly busy with the visual.

What interests me is how I can use the knowledge of the body into new forms. How can my body, trained in dance and with hours of ballet, transpose its way of thinking or dealing with problems into other disciplines. In the courses I gave at the art school KASK in Ghent, I did similar exercises: how to approach text through choreography, or how to approach sound as a body that you can also choreograph.

What I find important in Journal is that there is a very direct impact on the body and the perception of the audience. I want to offer them different formats of participating in experiencing theatre.

Fabienne, you invited the Finnish composer Maija Hynninen to write music for the piece. What attracted you to her work?

FS: Indeed, I got to know Maija’s work when I recorded a beautiful piece of her for Finnish radio. Maija writes masterfully for voice and electronics. She is very skilled at this electro-acoustic combination. We were curious about how we could go from the first purely acoustic part of the piece into another dimension, via amplification and live electronics. She seemed like the right person for this kind of research, also because she was interested in exploring the cross-over of disciplines. A lot of the material she used in her composition stems from the dance and sound improvisations we did with Benjamin.

HYOID regularly collaborates with performance artists, such as Myriam Van Imschoot or Ula Sickle. Do you share the same fascination for perception as Benjamin?

ANDREAS HALLING: Perception is not as central for us as it is for Benjamin, but it shows up in our work quite a lot. We come from a sound direction, but our last collaborations were with people who really manage this change of perception. Many artists say they want to make people experience things differently, but very few in my opinion really manage. That is what intrigues me with Benjamin, but also with Myriam Van Imschoot with whom we collaborated for newpolyphonies. They manage to really turn things upside down .

FS: We are trying to contribute opening up contemporary classical music, which is still a niche. We are interested in working with people coming from other disciplines as dance or visual arts and confront their practices and modus operandi with ours. The musical aspect stays important, we still want to create pieces that are musically relevant, but we want to make contact with the audience in a different way. Often, when you have a composer master on board for a long scale piece, the scores are too complex to be memorised – at least in the little time with have, and memorising is key to having a more direct communication with the audience. Our aim here is building an immersive soundscape in which you can connect without having to be an aficionado of contemporary classical music.

Through the collaboration with a choreographer, you shift from musicians to performers. How is it for you to be spinning and rolling while singing?

FS: It is quite intense, with the risk of losing control over our bodies and voices. We have to let go of virtuosity in this combination of singing and movement. We are in fact displaying more vulnerability because our bodies have more limitations than dancers.

AH: But it is also what we are looking for. We want to be part of creations, of the whole process instead of just performing the score. We both are quite bored with the standard classical music performance: you show up in your black clothes, stand up behind a music stand. You have very little contact with the audience and you also have very little connection with the music itself. The rehearsal periods are short, and you often only do one or two concerts. You do not have time to really dig deep enough in it.

BV: The collaboration indeed goes further than just trans-disciplinarity or exchanging practice. There is also an exchange in politics of work: how do you deal with work? When I said we are going to work for two months, for me it seemed very short but for Fabienne and Andreas, it was like a luxury. The creation of this piece is a meeting of two different ways of working.

What did you learn from each other in the confrontation of these work methodologies?

AH: There are more concrete things that we learned, such as the Laban Cube technique by William Forsythe. On a more abstract scale, it is about how you handle yourself because the rehearsal time is completely different in dance compared to in music. Music rehearsals take two times three hours a day. With Benjamin the structure is completely different, it takes the entire day. You have to learn how to handle yourself and dispose your energy in a new way. This can be sometimes quite hard, honestly, and also: you have to prepare yourself differently, physically and mentally. Many of the things we learned in the process, we can bring back into more traditional ways of presenting music.

FS: Some practices are quite athletic for us in the piece. Maybe it does not look like that from the outside, but I am really sore. (laughs) I realised that when you become a musician, you learn to listen to your body in a certain way, you try to get rid of tensions. When you feel pain, you are doing something wrong or you will end up sick. In this piece, it is hard to combine singing with physical work without adding extra tension. I have be quite sensitive in rehearsals because some gestures hurt. I need to find the threshold where the pain is tolerable and not a bad sign or something I should listen to.

BV: For me, it was interesting and very refreshing to go back to basics of movement. It is also such a gift to work with people you can bring out of their comfort zone and guide them. You know that their bodies will be able to achieve the results, and it is great to have two performers that are amazing singers, ready to do whatever you ask: rolling on the floor, swinging, spinning. Having the readiness of people that are so talented in something, to move to something else they do not yet master.

FS: We are also lucky because we did not have any dance and physical training during our studies. It is awesome still have the chance to grow and to develop different practices, even though are student years are way past us. I think, if we would be stuck in the sole contemporary music world, we would constantly be looking for more complexity in musical parameters only and after a while, that can feel a bit sterile.

BV: All these aspects are also what makes Un Journal what it is. It is a piece of oppositions: outdoor-indoor, acoustic-electronic, dance-music. Different worlds meet. The tensions between our ways of working and our background is what makes and sharpens the performance.