Performatik 2017 : 'Bodily Attempts at Social Sculpting': a reflection

an essay by Elize Mazadiego

Like its past iterations, Performatik 2017, Brussels’ performance art biennale, began with an assertion to experiment in 'social sculpting.' The term evokes the work of German artist Joseph Beuys who coined the notion of Soziale Plastik, translated as 'social sculpture', as the exercise of a creative act, much like the plastic material of art that can be molded, that could reshape society. By referring to Beuys, Performatik gives a sense of history from the 1960s, but considers his proposition in the context of the contemporary, provoked by a more urgent aesthetic inquiry into social systems and relationships, to which art historian Dorothea von Hantelmann outlined for us. Opening the biennale, Hantelmann’s salon asked the question: how can and does art generate new experiences of connectivity and encounter? Hantelmann seemed to suggest that performance art was a critical site of exploration and production into news forms of socialbility. The various artworks and performances featured in Performatik were variously tied to this motivation and therefore can be understood as sculpting the social body in one way or another. Within this general framework there were several other interventions and proposals for understanding visual art and performance in its expanded form.

This essay will attempt to give an overview of what took place, its interventions and resonances, while also reflecting on the continuities and ruptures. Due to the breadth of artists performing over nine days, a discussion of the artworks will be schematic and condensed in order to foreground the relationships and broader implications within the shifting and increasingly transdisciplinary field of performance (art).

(Performing objects)

Hantelman’s position as an art historian speaking about 'live art' is symptomatic of the current dialogic mode between the visual arts and performing arts. As the visual arts explore theater’s durational, embodied and collective tradition and the performing arts experiment with sculptural and painterly forms, there is an effort to disrupt and innovate their respective disciplines, but there is an equal amount of questions and problems that emerge from this cross-pollination. Over the years Performatik has been at the centre of this chiasmus, emblematic of this were the biennale’s opening pieces: Grace Schwindt’s Opera and Steel and Miet Warlop’s Crumbling Down or Hedwig Houben’s Imitator Being Made. Schwindt, Warlop and Houben identify as visual artists in some capacity, but continuously engaged the structures of theater and performance. Within Performatik this was displayed in their delicate fusion of performers and sculptural objects or body and material form.

Schwindt’s Opera and Steel breaks from the medium of film and the context of the museum to stage her performance live within the black box. A cast of diverse characters stoically move, sing and speak an ornithologist’s harrowing account of sea birds impacted by oil pollution. The narrative’s socio-political underpinning was secondary to the formal play through which the story was told. Her combination of animated performers — speaking, singing, dancing and performing acrobatics —with static sculptural steel objects show the capacity for sculpture to perform, with temporal and dramatic characteristics that endow it with liveness, and subsequently transform it into surrogate performers. As Rosalind Krauss argues, through a reading of Gotthold Lessing, sculpture (in its traditional form) is 'an art concerned with the deployment of bodies in space’.[1] Space in this case however is defined and activated though the unfolding of the performance, which similarly acts on the object. Schwindt’s ‘Pierced Mermaid’ is that object that creates a dialectic, becoming one of many bodies in this narrative that resonates the violence in Opera and Steel.

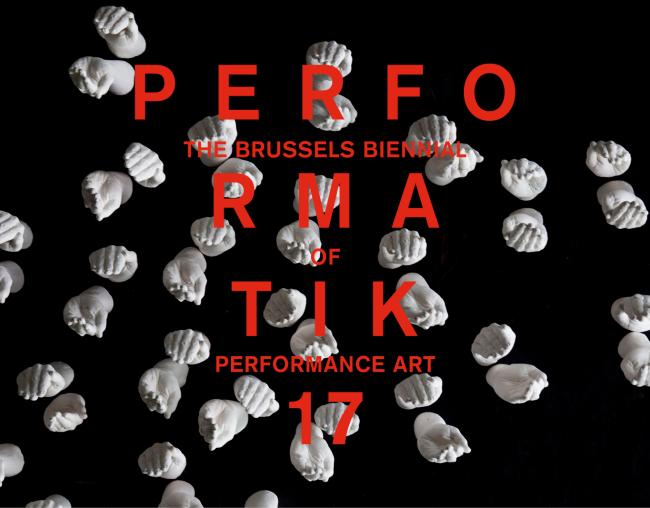

The fluidity of artistic media was similarly evoked in Warlop’s Crumbling Down. Described as a ‘sculptural live event’, Warlop’s performers repeatedly clapped their ‘hands’ made of white plaster, consequently breaking the material into shards that smashed to the floor. The resounding tinkering, breaking and eventual blow to the floor dramatized the uncanny vision. Sculpture in this sense is shaped by the performance, meaning these objects fit within a narrative that has a temporal frame from its beginning and end, closing the performance with its very document: the preservation of broken plaster across the floor as a final sculptural installation.

Houben’s performance revolves around a central sculptural object, a large plaster head, to which her lecture-style execution considers the essence of the object. Very much in dialogue with Warlop and Schwindt, the artist imbues meaning and vitality into her object through representation. Representation as much as the performer’s body is the central interlocutor in the sculpture’s liminal status as subject and object. Houben unifies these artists’ gesture towards injecting the sculpture’s vacant physicality with presence.

(Animating Images)

The liveness of inert matter is again articulated in the works of Philippe Quesne’s Caspar Western Friedrich, Ola Maciejewska’s Bombyx Mori or Kristof Van Gestel/Manoeuvre & Heike Langsdorf’s Vormfrakken who ask what it would mean to experience a painting or textile, extending it beyond it original frame or context? In Quesne’s piece the imaginary of German Romantic landscaper painter Caspar David Friedrich is performed through the vernacular of a Western genre. Cowboys are painters as much as poets and performers. Their role is to interweave these various dimensions into a composite that breaks open the purely visual into a multi-sensorial experience of the sublime. While Quesne makes present Friedrich’s work, we are never given the opportunity to mistake the artwork with reality as Quesne repeatedly reminds us of representation’s artifice.

In thinking about the assertion of presence as 'shaped within an ecology of relationships; in the realisation of an environment, in a layered experience of temporality' Bombyx Mori and Vormfrakken’s fluid textile forms are made present through its dialectical relationship with the body that wears and moves it.[2] The various textiles in Vormfrakken are remade as bodily composites and interactive corporeal devices, multiplying the material’s possibilities as much as the body. Something in Kristof Van Gestel’s suggestion that Vormfrakken are objects 'charged up by the whole social process in which they were created' takes us farther afield, but back to the main premise of Performatik in 2017. His comment pinpoints peformance’s socially relevancy. For Kristof Van Gestel and Manoeuvre the generative process over collectivity and embodiment was what animated their work, turning their art form into an experiment of sociality.

(The 'social' turn)

Shannon Jackson contends that 'social art' practices are heterogeneous, alternately motivated by political action or aesthetic inquiry, but together forming a porous definition. The same can be said of the artworks featured in Performatik, approaching the topic of the social in diverse and complicated ways. Perhaps the more explicit versions of performance’s 'social turn' are Daan ‘t Sas and Lotte van den Berg’s Building Conversation or Maarten Vanden Eynde and Alioum Moussa’s In_Dependence. Both pieces are motivated by dialogue that has a social dimension as the artist and participants are together, engaging in conversation about a particular topic. Also crucial to these pieces is their transformative effect, as the participants enter into a shared space and time, and leave changed by their experience. Different from Kate McIntosh’s In Many Hands which forms social conviviality through the haptic, these pieces situate conversation as an integral part of the work. Akin to Grant Kester’s notion of 'dialogical aesthetics', Building Conversation and In_Dependence are 'the creative orchestration of collaborative encounters and conversations', outside of institutional frameworks or spaces, that attempt to 'catalyse powerful transformations in the consciousness of their participants'.[3] Within the framework of Performatik the provisional sense of collectivity would seem to the operative mode of 'social sculpting.'

Beyond the social configurations that these works propose, I would argue that on an individual level, there are other propositions that move towards quietly observing, perceiving and reexamining our conventional social fabric, rather than inventing a new one. Ant Hampton and Tim Etchell’s The Quiet Volume and Benjamin Vandewalle’s Peri-Sphere utilize techniques of disruption and disorientation, alternately working within a theater of illusion and reality, to reveal the social situation we are in. The Quiet Volume exemplifies Hampton’s engagement with the paradoxical dynamic of social convention. By leading the participant and reader through a series of audio and textual cues to reflect on and facilitate our perception of specific space and time of the performance, moving in and out of the context in which it is set in (public library) and its representation. Hampton’s second work featured in Performatik, Someone Else, ventures even further into public space and into our everyday social relations by asking participants to reflect on their social sphere and initiate a social interaction with someone outside of that. In ways familiar to Brecht’s V-effect, Hampton’s pieces strip the social space and context of its familiar qualities, making them visible within our field of perception and awareness. In a similar mode Vandewalle’s Peri-Sphere invites participants to lie in a mobile periscope through which you see a fragmented view of the Galeries Royales Saint-Hubert. The artist destablizes the 'natural' context, making the familiar truly strange, and thereby effectively dislocating us from our normal, habitual experience in the public space. Questions remain as to the degree to which Brecht's social shock is induced, but Peri-Sphere forces us to look at our immediate environment anew.

(Performing history)

Despite the allusive resurfacing of performances’ antecedents within Performatik, the biennale resurrected two historical figures from the visual arts and performance camp: French artist Yves Klein and American dancer Loïe Fuller. With Performatik seemingly focused on the present and future of Performance, the exhibition of Klein and symposium on Fuller take a moment to examine the past, while inserting it into our understanding of the present. The dialogic relationship between past and present is exercised in Miet Warlop’s Horse. A Man A Woman A Desire for Adventure and Pieter Van den Bosch’s Paint Explosions, which opened the exhibition Theater of the Void or Trajal Harrell’s Caen Amour and Ola Maciejewska’s Bombyx Mori, dance performances which derived from their research on Fuller.

The monographic exhibition of Klein, featuring over thirty works, showcases the postwar artists’ intermedial expansion with a body of work across painting, sculpture and performance. The question of Klein’s relationship to performance can be understood in the ways his Anthropometrics — a series of paintings produced from female models imprinting their bodies covered in International Klein Blue pigment on canvases — foreshadowed performance’s expressive potential of the body and its fleeting presence. The enduring artifact, the model’s bodies transposed on canvas in the shape of wild gestural abstractions, is reminiscent of Jackson Pollock’s body in action that Kaprow would later mobilize to create Happenings. But it is Kaira Cabaña’s description of Klein’s work as a form of 'performative realism', a mode of J.L. Austin’s theory of performative utterances that constituted tangible reality that best reveals a critical historical moment when visual art and theatre converge, bringing us closer to our current expression of performance art.

Warlop similarly operates at this intersection to develop what she calls 'living images', evoking parallels to Klein’s own 'living paint brushes'. For Warlop the materiality of her work is only operable within the performative body, which is perhaps where we can locate the resonance between Warlop and Klein. Pieter Van den Bosch’s Paint Explosions however bridge parallels to Klein’s definition of color as 'spatial matter that is at once abstract and real'. Similar to Klein’s Planetary Reliefs, and to some extent Niki de Saint Phalle’s colorful shooting paintings Tirs, Van de Bosch’s painting is conceived as a performative gesture executed in space and time to which the diaphanous walls splattered with paint is a visual record of the event’s explosive energy.

While Klein holds a comfortable position within performance’s genealogy, Loïe Fuller’s place within this history is only beginning to be reconsidered. Performatik’s reconsideration of Fuller’s work is paired with Harrell and Maciejewska’s attempts to revive her diminished role in modern dance, both cementing her into the performance canon. As much as a progenitor of modern dance, Fuller’s innovation was her transdisciplinarity, weaving visual art, film and theater into her dance practice. Rhonda Garelick’s description of Fuller’s performance as 'sequences of ephemeral sculptures' recalls the same fluidity that Performatik’s artists embody.[4] Rather than turn to re-enactments of Fuller, Performatik featured contemporary works that engaged in performing the archive. Ola Maciejewska’s Bombyx Mori translates her research on Fuller into a choreographic performance composed of three dancers who similarly dance swathed in large billowing material that transformed the body into moving sculptural objects. Interestingly Maciejewska proclaims to work within the liminality of Fuller’s work as Bombyx Mori operates between body and object, movement and stillness, past and present.

Harrell who is 'interested in going into the gaps and fissures' presented Caen Amour as a hybrid between Fuller’s juxtaposition between costume as object, the raw, contorted movements in Japanse Butoh and the erotic spectacle of Orientalist Hoochie-coochie shows. In spatial terms, you as the audience also move across physical boundaries, shifting your perspective across a bisected stage. Through Fuller’s experimental postures Harrell explores his propensity for rupture and newness, but ultimately Fuller is a foil for reflection and departure into his own post-modern language. In what I have drawn out from Performatik’s program and performances Harrell’s Caen Amour is emblematic of a larger concern within performance as a historical process of experimentation whose imperative is to juxtapose, complicate, cross-pollinate artistic disciplines. In the end no single artist or viewer is comfortably situated in any one category. In this transdisciplinarity is however the advancement of social engagement in performance. Caen Amour takes its cue from post-colonial studies, which has its own repertoire of social justice and progressive formation, but does not wholly represent performance’s social turn or attempts at social sculpting. However Harrell’s quote of scholar Trinh T. Minh-ha saying, 'the story depends upon every one of us to come into being. It needs us all, needs our remembering, understanding, and creating what we have heard together to keep on coming into being,' returns us to the biennale’s original proposal to imagine something together.[5]

Elize Mazadiego is an art historian and critic working at the intersection of the visual arts and performance studies. She is currently writing a book manuscript that rethinks the notion of Dematerialization through performative, non-object based artistic experiments. Her writings have been featured in Frieze, ArtNexus and Etcetera, among other publications.

[1] Rosalind Krauss, Passages of Modern Sculpture. MIT Press, 3.

[2] Archaeologies of Presence: Art, Performance and the Persistence of Being, edited by Gabriella Giannachi, Nick Kaye, Michael Shanks.

[3] Kester, G., 2005. Conversation Pieces: The Role of Dialogue in Socially Engaged Art. In Z. Kocur and S. Leung, eds. Theory in Contemporary Art Since 1985. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 76-100.

[4] Rhonda K. Garelick, Electric Salome: Loie Fuller's Performance of Modernism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

[5] Trajal Harrell in Conversation with Ana Janevski. https://www.moma.org/d/pdfs/W1siZiIsIjIwMTYvMDkvMTkvcjI1c3g1eTltX1RyYWph...