MAKING something HAPPEN by doing nothing

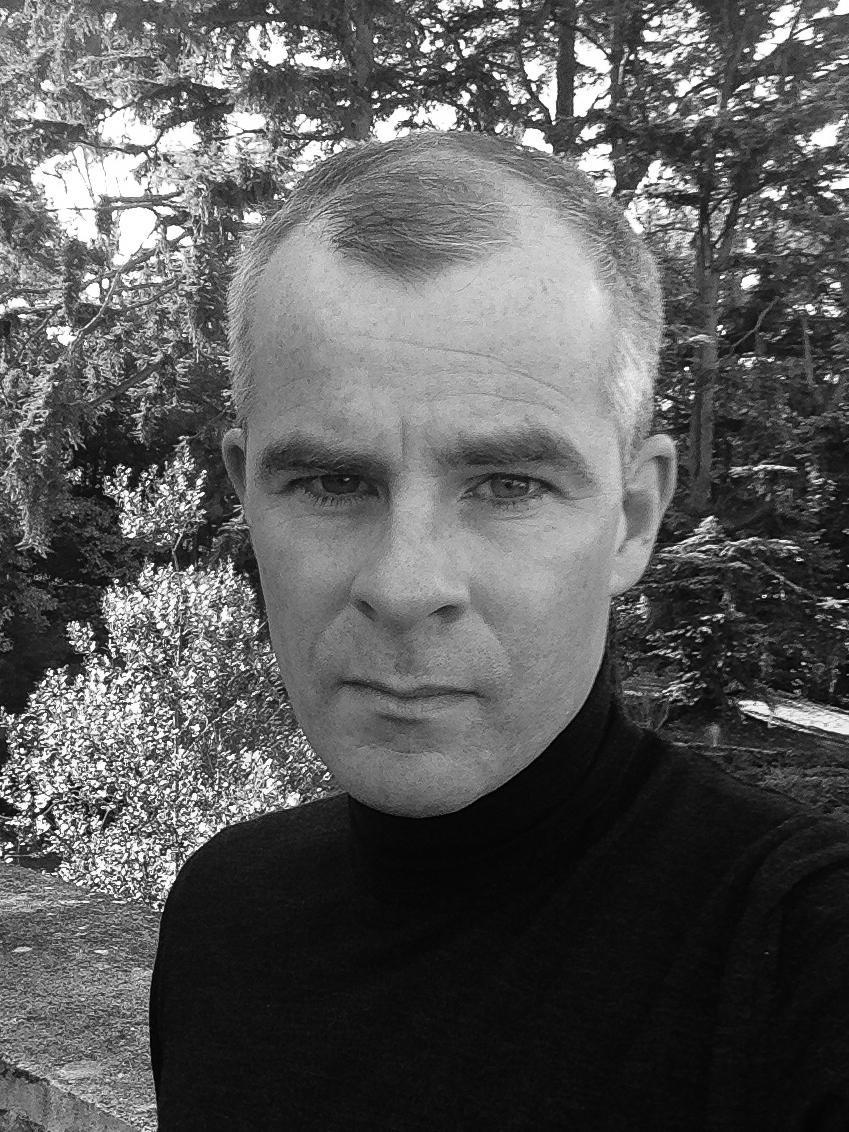

David Weber-Krebs on The Guardians of Sleep

Several of David Weber-Krebs’ productions have been staged at the Kaaitheater in the past, including Balthazar (2013), Into the Big World (2015), and Tonight, Lights Out! (2016). His work combines profound complexity and razor-sharp clarity. In changing forms and representations, he plays on his audiences’ expectations and powers to act, as a leitmotif throughout his work. In his new production The Guardians of Sleep, he focuses on sleep. But this is not so much the subject of the show as an activity that occurs onstage. How do you present something passive like sleep in an art form like theatre, which is still based on principles like presence, communication, and expression?

How did you conceive of the idea of focusing on sleep in The Guardians of Sleep?

In my work I explore the porosity between what is happening on stage and what is happening in the audience. This fragile and sensible situation interests me because it is unique. Something is at stake. In the book 24/7 by Jonathan Crary, I read about sleep as the last human action that has not been colonized by capitalism – because you neither produce nor consume anything while sleeping. This makes sleep both a very valuable and precarious thing, fragile by its very nature. I thought it would be interesting to turn Crary’s reasoning on its head and to see what can be generated when you put sleeping people onstage. Would it elicit a sense of responsibility or care from the audience?

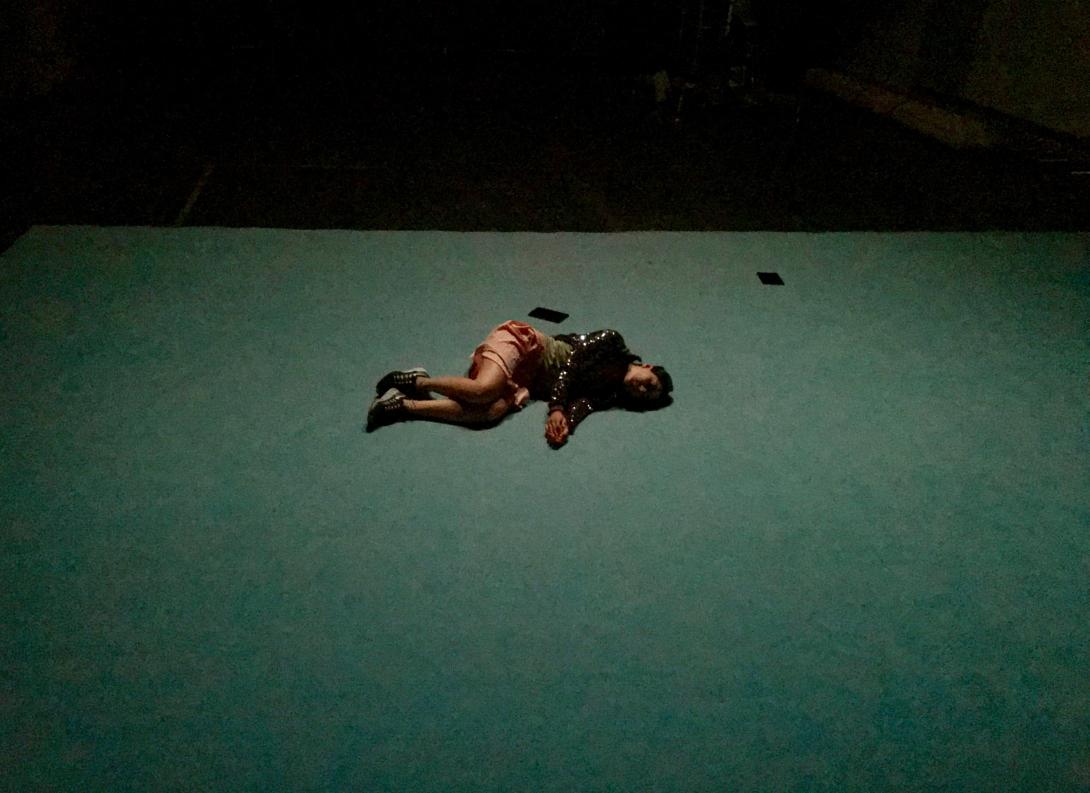

The performance has various parts. Performers start as active storytellers. They introduce themselves to the audience with images and stories from their own lives before entering gradually into a sleeping mode.

What is the relationship between these personal stories at the beginning and the rest of the piece?

They create a certain proximity between the performers and the viewers. If somebody tells you a personal story and then lies down silently in front of you, you remain with that person in various intimate ways. In the rest of the show, those images and stories return as a collective memory, as mental projections.

The performers are like reclining sculptures – but sculptures that look back at you. And then they close their eyes. You are the last image that they fall asleep with. Perhaps you will appear in their thoughts or dreams, just like their images and stories will continue to appear in yours. These things are all possible, but you can never really be sure about it. When somebody closes their eyes and withdraws mentally, you don’t have access to that person anymore.

Onstage, you employ various elements that exude an aura of authenticity, but which might be fictional: personal stories and bodies that fall asleep. Does that fine line between fiction and non-fiction play a role in this production?

It has struck me that the premise of this production often leads people to wonder whether it is at all authentic, whether sleep is really produced. But theatre as such is a space for fiction, and it precisely that fiction that offers us a certain sense of security. The convention of humanist theatre is that performers express themselves actively to an audience, for example by talking of moving. Here performers can defy this convention by closing their eyes and removing themselves – literally. This inevitably has consequences for the audience. At the end of the day It is not about the literal situation, but about what is happening in that shared space, where watching other people’s private lives or sleeping bodies doesn’t make us voyeurs but active participants in a communal process.

How does it make the audience react?

The show starts in a rather classical way with the performers and the audience in their respective roles. The more the performance advances the more this situation disintegrates. What remains is a collection of bodies that are no longer in an actively observing position, but which – just like the performers – have ‘removed themselves’ from the situation. This creates a community that has abandoned all its expectations. But because this process is so sensitive, the tension remains palpable in the space.

Despite – or perhaps thanks to – the fact that the conventional arrangement between the viewer and performer is broken, a new relationship is forged. The production becomes a moment of shared time and space, in which you experience something together as a group. Was that your aim in looking for fragility?

Donna Haraway talks about ‘response-ability’ for what she calls ‘a practice of care and response’ between all type of agents – people, things, animals, the sky… This is precisely what I was looking for. I wanted to make it visible and tangible that we share the same oxygen in that time and place in the theatre. And thus to make it clear that every person present has a part to play in this temporary community – and that a certain negotiation is necessary. In The Guardians of Sleep, this idea grows as the show progresses. The concentration of the bodies and the fact that they gradually stop moving and fall asleep, or at least try to, exacts sensitivity from the audience. This creates a tension that makes every gesture and movement important, and even every breath almost. Everything gradually comes to a standstill. This generates something new. It changes the way you are and the way you look in the space: you are a body surrounded by other bodies.

So who are the ‘guardians’ of sleep?

In a certain sense, the audience ‘guards’ the sleeping performers, and this elicits a sense of responsibility. But the performers also remain just as responsible for the situation they have created: they continue to produce silence, even after they have withdrawn themselves.

The idea of responsibility is a recurring theme in my work. In Tonight, Lights Out!, for example, everyone in the audience was given a switch connected to one little bulb. My proposition to them was that they would create a complete black out. The audience controlled everything and was responsible for the resulting group dynamic. Or in Balthazar, for example, in which a donkey was simply let loose onstage, along with a group of performers. When the audience made a noise, the donkey reacted, so the performers had to attract its attention again. The donkey itself obviously made no distinction between the performers and the viewers. I think of theatre as a situation everybody shapes together.

In The Guardians of Sleep, you import sleep into a context where it does not really belong. Not that viewers don’t sometimes fall asleep at the theatre, but its explicit presence on the stage feel very contrarian. In the announcement for the production, you referred to resistance and disobedience. Do you think sleep, as the last anti-capitalist act, have activist potential?

While creating the production, we discovered a text about apathy syndrome among migrant children in Sweden. The children of families who were going to be deported would fall into a deep sleep – a coma almost – as a reaction against the terrible situation. The long period of waiting and the final answer that they would have to leave their familiar environment made them literally paralyzed. For some children, this could last for months or even years. The phenomenon was described and indicted by numerous doctors and psychiatrists. The text talk about a young man of Chechen heritage, who was ultimately allowed to remain in Sweden with his family because of what had happened to him. By doing nothing, by sleeping, he actually made something happen.

Sleep is a very powerful ability because it thematises safety and security. You can only sleep when you are safe. The Chechen boy later described how he felt as though he was in a glass box, and he didn’t dare to move in case he broken the cocoon. In the theatre, sleep is likewise a kind of anti-act. It highlights a taboo or a fracture: the performer turns inward instead of being expressive. We see how he or she retreats into a dimension that we cannot grasp. But we are drawn into that dimension too and forced to share the experience somehow.

Your production has a certain duration, with a beginning and an end. Doesn’t an anti-act like sleep presuppose a longer experience? One might expect an open-ended show, like Tonight, Lights Out!, in which everyone decides for themselves when it ends.

It is very important to me that when you leave, you feel as though you have experienced a theatre production with a beginning and an ending. This intense concentration makes you feel as though you have had a collective experience. After the première in Mannheim, somebody told me that there is a profound sense of solidarity in the show. It may only be possible to elicit this feeling if the show is experienced as a group from beginning to end.

Interview by Esther Severi (Kaaitheater).