Savoir plus - Grinding the wind

Ici vous trouvez une description courte du spectacle et la distribution.

Artist Spotlight with Dina Mimi

Interview door ArteEast als deel van hun Artist Spotlight series. Het interview verscheen in juni 2022.

About Dina Mimi

Dina Mimi (born 1994, Palestine), is an artist who lives and works between Jerusalem and Amsterdam. Her practice encompassses video, sound, performance, and text, and examines the body/space in Palestine. Her current research is concerned with death in the public sphere, as well as notions of visibility and invisibility between archaeology and the object, and the museum and death.

Dina obtained her Bachelor’s degree from Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem in 2016, and her MFA degree in Art in the Public Sphere from ECAV-École Cantonale d’Art du Valais in Switzerland in 2018. She is currently a resident of De Ateliers in Amsterdam.

About her research and work

Can you tell us about your work in general and the main themes you return to in your practice?

I mostly work with sound and video, as well as through staged readings and performance. My practice tries to sever heavy matter into soothing sounds, and to create narratives that are reflections of the past. I ask: What does grief sound like? How do we search for fictional fractions within historical accounts? My work also consists of extended research into death and memory, especially in relation to historical events and the colonial past. I think about how bodies embrace the struggles of the past to the point of sacrificing themselves, as well as contemplating encounters of the present and their prospective futures.

Can you speak to your experience pursuing your MFA in Switzerland at the École cantonal d’art du Valais (ECAV)? How did this affect your practice? What did you produce while there?

The program in Switzerland was experimental and so, was constantly changing. In my experience, I’m not sure if that was helpful. I do have a lot of scepticism toward arts education, and especially programs that follow rigid systems whilst calling themselves experimental or alternative, and use “diversity” as a token term for optics when the opposite is true. I learned about the inner workings of tokenism the hard way, since it affected me and several peers personally. A lot of racist encounters shaped my time in Switzerland. They needed to be addressed but usually went unheard and unseen because of administrative complicity. For me, the most important thing that happened was meeting my peers. Each one of them has helped me learn valuable things, by making me question my environment and helping me throughout everyday obstacles. People like David Romero, Sinethemba Twalo, Sarah Ibrahim and Chrisantha Chetty; I am grateful for and to them, not for the MFA program itself. Having come from a department of glass and ceramics in my undergraduate studies, I found myself producing work in new mediums during my Masters. Since then, I realized my first performance, Nobody died yet in this house, which was a continuation of my thesis in Switzerland.

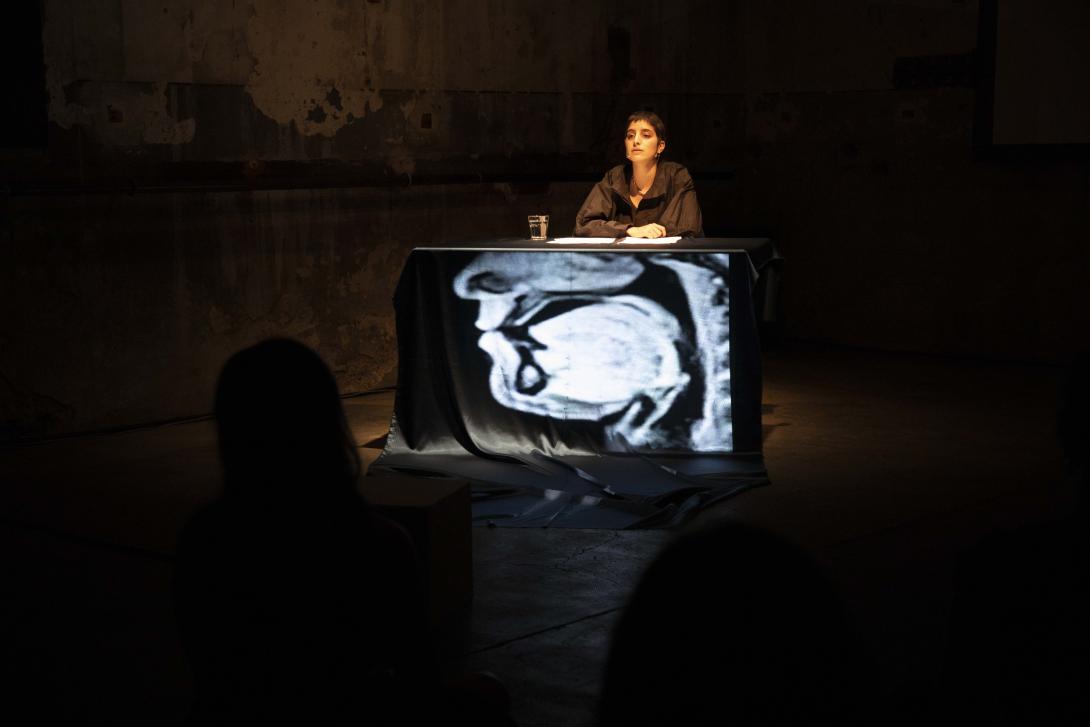

Tell us about the works that came about from your thesis in Switzerland, namely the installation lecture performance, Nh.

The thesis contains two chapters: The first is about madness in public spheres in Palestine and the second is about the self-immolation of Sebastian Acevedo during Pinochet’s dictatorship in Chile.Nobody’s died yet in this house explores the concept of the body in public space and the repetition of history through figures with similar names and destinies. Oudeh Mtair from Qalandia Camp (also known by the names, Abo Nahed and Hammurabi), is a character that appeared after the martyrdom of his son Nahed, whose cousin was also named Nahed after him. How could it be that they were named the same name and died the same death? It’s as if they were remembered as one–a singular martyr who died twice. How did Yusuf al-Sudani, who lived in Ramallah, move his body in circles until his death in 2016, in the middle of the square? Isn’t history also cyclical? Does space consume madness, or does madness engulf space? The square is the centre of the city and a starting point for the work. Public space is a theatre for this kind of performance; in order for it to happen, an audience of onlookers, recipients, and participants are required to witness it unfold. I consider it a moment of madness, one through which you’re looking at reality from the ground level, meaning, through the daily actions that force some individuals to commit suicide, martyrdom, body protest, and in most extreme cases, self-immolation. At that collective moment, there is no escape for anyone, only a vortex of action and responsibility.

Can you expand upon the themes of repetition and death, as well as how these cycles reappear within your research and work?

As I’m writing, I received a message from a close friend of mine. It was a picture of Amjad Fayiz, a child who was killed today by Israeli soldiers. He was named after his uncle who was killed in 2002. Amjad Fayed was 17 and killed with 11 live bullets. Twenty years later, Amjad is killed again. This happens quite commonly in Palestine. Naming a child after someone who has been killed is a way to honor and appreciate a martyr, but no one ever expects the same exact fate to await the person being named after them. I guess this says a lot about the particularly cruel nature of Israel’s settler-colonial violence. It’s not pure coincidence, it just attests to the proximity to death by execution that Palestinians are subjected to.

Talk to us about your work In Order to Talk with the Dead. Can you elaborate on the significance of this piece within the larger context in France today?

In Order to Talk with the Dead is a short video that was made in 2018. It follows the circulation of “trophy” skulls in relation to their place of origin, Algeria, and visitors to a museum in France. French colonialism is forever replicated in the museum as it turns these skulls into objects devoid of history. They’re exhibited and made to be engaged without any origin, explanation, or name. The video was made from found archival footage shot by the French in Algeria during their mandate. It examines the relationship between the museum visitor, who perceives the skull as an object, and the skull, which gazes at the visitor as a mortal. Is the gaze between them reciprocated? Is the visitor being seen by the skull? The museum is a privileged site for these encounters to take place; it possesses powers that alienate and disorient visitors from their own history. On July 3rd, 2020, French president Emmanuel Macron made the decision to return twenty-four skulls belonging to deceased Algerians back to Algeria.