‘There’s an overall craving for a feeling of trance’

In conversation with Gisèle Vienne

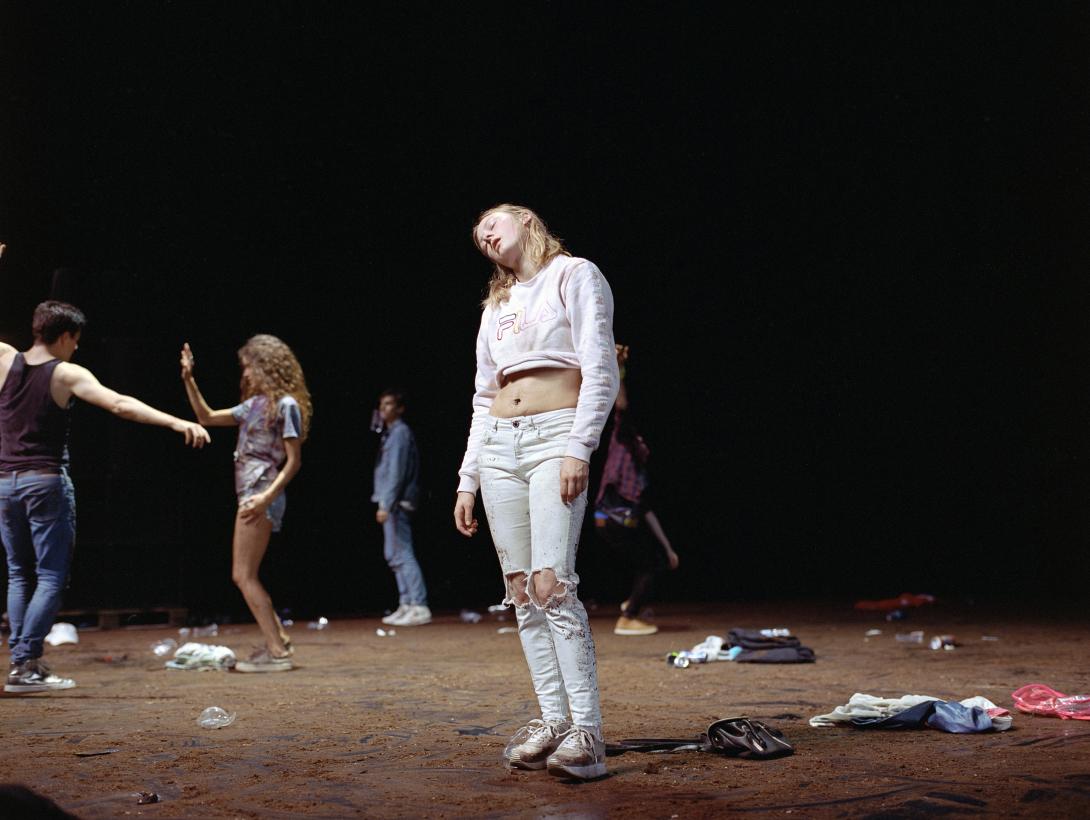

What happens when a group of people gets into a trance in which they release all their tension and aggression? How do group dynamics actually work? For CROWD, French artist and choreographer Gisèle Vienne invited fifteen youngsters to surrender to the techno beats of the 90s. We meet her some weeks before the premiere, to talk about the presentations and representations of violence, Indonesian rituals, and artist-made funerals. ‘Art truly is a legitimate context to deal with death and violence.’

In CROWD you approach violence from a different perspective than the usual negative one. Is there a need for a new discourse on violence?

GISELE VIENNE: For many years, I’ve been working on different types of violence – among many other topics. Violence and death are often considered negative. Violence has always been part of humankind, irrespective of whether it was considered civilized. Humans have made and searched for confrontations with violence for thousands of years, including in art. Just think of the cave paintings in Chauvet, of which I discovered the replica last summer. So it’s surprising that in the 21st century, some people still wonder why I treat these topics. How do we deal with the different violent impulses inside us? And with other, improper thoughts that are so hard to express? It’s a very old concern.

I have a deep preoccupation with the ways societies and communities create spaces and situations in which violence, and other emotions and thoughts, can be expressed and exchanged within an intimate dialogue, without being disrespectful or causing damage to the community. I think art could be such a space.

Nonetheless: if the various ways of expressing violence during a party – be it regulated, unregulated, or represented – were one of the starting points of Crowd, the process changed a lot along the way. These questions are still there, but they are more peripheral. I don’t think I necessarily approach violence from a negative angle: I attempt to create more nuance in approaching its different expressions. And CROWD tries to contribute these additional nuances too.

Rituals have fulfilled these needs for a long time as well. The representation of and the dialogue on violence – and other improper feelings and thoughts – are possible behind the shielding force of art. We certainly need to continue these rituals and invent new ones to respond to these needs. But the first step will be to identify, analyse and understand them. Some artists, but also politicians, sociologists and psychologists are exploring these issues. A better dialogue between the different schools of thought, and more effective collaboration, would certainly benefit the organization of our society with respect to these concerns.

Talking about rituals: in this season’s focus programme RE:RITE, Kaaitheater is investigating rituals. By reflecting on the relevance of existing rituals, but also by looking for new rituals in artistic practices. What place do you think art should have in rituals nowadays?

We should never underestimate the importance of the quality of the artistic experience in rituals, such as for example weddings and funerals, or any other ones. When a non-religious state does not propose a strong artistic quality for these symbolic moments, people could perhaps think that religion is a stronger spiritual space than non-religious communities.

I guess everybody is somehow looking for deep and spiritual experiences in life, whoever you are, wherever you’re raised and whatever tools you have. Artists should be far more involved in these aspects of society. It would be very interesting if you could choose, for example, to have a Matthew Barney funeral or a Pierre Huyghes version. As the purpose of these events is very specific, they should probably work closely with psychologists, sociologists, etcetera, to make sure that they’re fulfilling the complete range of tasks that a funeral implies. It is a spiritual moment where people face many deep questions, but also a strong moment of social cohesion. Psychologists and sociologists are, of course, more competent than me to describe these various roles and aspects.

What happens when you represent violence? Does a transformation occur? What is the value of this transformation, for example, while experiencing CROWD?

There are many ways to represent and suggest violence. I’ve mainly been working with suggestion, far more than representation. From the very beginning of the rehearsals for CROWD, I was surprised by the enormous pleasure and sensuality of performing, watching, and dealing with violence in this specific context. So I thought it would also be interesting to enhance and focus on this pleasure and the powerful and wide variety of sensations that arise during a party. A party with a great range of emotions and behaviours in the specific formal way we chose, where time is completely distorted by specific choreographic rules.

You clearly bring the notion of physicality onto the stage by having CROWD’s crowd dance to very rhythmic beats.

The physical state of the performer, and the physical experience of the audience are central concerns in CROWD. For CROWD we decided to focus on a techno rave party in the early 90s, with its utopias and drug culture in which new rituals were created, or at least dreamed up. In reality, this often remained very clumsy: there was a big gap between utopia and reality. Nevertheless, some of these attempts really were strong and carefully considered. It was another way of looking for the experiences for which society didn’t offer the right spaces. These parties and this culture were often just seen as kids who wanted to get crazy and entertain themselves. But I think most of the time people were actually looking for deeper experiences.

Instead of playing tracks, deejays mixed uninterrupted sets, creating the feeling of one long composition during parties that would last all night and day. There’s an overall craving for this feeling of trance, which can be triggered by dancing, a lack of sleep or taking drugs. In CROWD we work with these experiences of altered perception – and the questions related to it. These questions also recur in my other pieces.

How do you transfer this experience of trance to the audience?

I don’t think the audience will experience this trance, or that I will effect it in them. But we will certainly question our perception versus their perception, as well as the way music, light, and movement can influence and alter them.

The subjective experience of time and its distortions is central in CROWD. We worked on rhythmic distortions and the performers’ specific quality of presence. Optical effects, and especially Patrick Riou’s light, can also provoke a feeling of clarity – as well as a simultaneous confusion. My work in general, and especially CROWD, is often inspired by retouched movements, the possibilities of artificial bodies, and the possibilities of film-like editing and special effects such as slow motion, cut movements, edits and accelerations. All these are triggers for this state of clarity and confusion.

We try to find a very personal and sensitive approach to these triggers, so that the personality of the performers can be enhanced through them. The superposition of the qualities and styles of these kinds of movements not only has great choreographic and musical value, but is also dramaturgically and narratively important. It creates interesting rhythmical vibrations to which you can attune, and which eventually have a somewhat hypnotising effect.

When you step inside a theatre, everybody has a different rhythm determined by the state and situations they were in before entering. The rhythm of the piece can ultimately attune their bodies to the musicality of the piece. I experienced that very clearly in Japanese Noh-theatre.

Do the performers also experience a kind of trance?

I don’t know, I would first have to understand these kinds of states better. But it is true that the performers will often be in a specific state during my pieces. At least that’s what we try to achieve. We try to work from real feelings and a very present state of being to avoid faking anything. The text by Michel Leiris (1) on theatrical aspects of trance describes essential differences between ‘théâtre joué’ (played theatre) and ‘théâtre vécu’ (lived theatre). This analysis seems to me to be essential and interesting for the states of being I’m looking for onstage, and I think this is a more essential experience of performance.

Thanks to Arco Renz, we went to Indonesia in the framework of EUROPALIA INDONESIA, along with photographer Estelle Hanania and musician Stephen O’Malley. We had the opportunity to see many different rituals, in which some people reached trance-like states. This was not something I had expected. I tried to watch them and experience the situation in the most accurate and open way. Of course I was still conscious of how much of a foreigner I was, and I tried to understand what I could, which was probably not much.

You talk a lot about the collective experience of the audience and the dancers. At the same time, everybody is having an individual experience. Is this something you make visible somehow?

I really try to work on an individual level, indeed. I addressed the functioning of groups in The Ventriloquists Convention: what makes a community a community and how are all these people also very isolated persons that even feel lonely and different from the rest of the group? In that sense, CROWD feels like a gallery of portraits.

I’ve thought and experimented a lot to discover how many people I had to put on stage to have a crowd, while still being able to see every single one on their own. For Crowd, fifteen was perfect. You can take the time to observe each dancer through the specific form of the piece. Each body is a full story, a whole book, which creates a very strong density of narratives. It’s like a rich painting with many little details. Even if you were to watch it several times, you would never be able to see everything. I hope to trigger the same experience in CROWD. Not in a frustrating way – but in a very exciting way.

A conversation with Gisèle Vienne, by Lana Willems & Eva Decaesstecker (Kaaitheater)

(1) Michel Leiris, La possession et ses aspects théâtraux chez les Éthiopiens de Gondar, 1958.