| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

20

|

21

|

|

22

|

23

|

24

|

25

|

26

|

27

|

28

|

|

29

|

30

|

31

|

|

|

|

|

Read more - Solos and Duets

Here you find a short description of the performance and the credits.

'We are addicted to dismantling things'

An interview with Meg Stuart by Aïnhoa Jean-Calmettes and Jean-Roch de Logivière, originally published in Mouvement in March 2018. Edited and condensed for clarity.

To cross disciplines, the American choreographer Meg Stuart has always pushed the boundaries of contemporary dance. Whether it is by putting her finger on the sore spot, or to alter the conscience of its spectators, she continues to believe in the critical power of her art.

A few years ago, somebody called your work a “dance of disaster and disenchantment”. What do you think of this statement today?

“I’m not afraid of tackling head on the dark side of things, which would be easier to ignore, such as our relationship with our body, or our human condition. I’m not afraid of making the spectator feel uncomfortable either. There is a sense of urgency in my work but I don’t just make a statement about chaos. I’ve always had the conviction that my choreographies essentially expressed a desire for change. Dance is an important medium because it’s inherently critical. It’s a medium that unravels contradictions and refuses simplistic definitions. Dance does not refute complexity, however. On the contrary even, it acknowledges its benefits and urges us to embrace them. All truth contains the opposite of truth.

In my early works, it seemed more difficult to find solutions. I sometimes think that we are all addicted to suffering. To the dismantling of things and to chaos. We sort of hope that we’ll find a way out. This doesn’t mean that I think that we should avoid comfort and facility at all costs. It is important, however, to keep a higher goal in mind: not just a “dance of disaster” but a sort of empowerment, a desire for change and hope. It is important that you come up with proposals in addition to being very critical.”

What do dance and choreography teach you today?

“I never dance thinking that it may change people’s perception or their sense of time, or teach them that you can exist in different dimensions. Having said that, improvisation, trance, various states, or the reproduction of a gesture may allow you physically to approach those states that have been described by neuroscience, quantum physics or research about memory. Obviously dance has therapeutic powers, but it also allows us to redefine our relationship with the world or to alter our conscious by tapping into the body’s intelligence. It can be a very euphoric experience, and I think that most people have no idea that dance can transform reality like this. We dance for the same kind of reasons that people take drugs. I’m convinced that asking physical and spatial questions, and trying to answer them with your body, in spaces that are constructs, allows you to change your understanding of these questions. I think that dance can make us more open, more compassionate, can teach us to listen and look more attentively. My artistic creations always look at how social relationships are changing.”

Does this also apply to the visual arts and cinema, or just to dance?

“I’m interested in how dance can communicate with other forms of art, and I think that this transcendence is vital. It is important that you interpret dance in its widest possible sense. Language is endless, unlimited. Our interpretation of the notion of dance must also be very flexible.”

Is contemporary dance defined by the intensity or the quality of the movement, rather than by the movement itself?

“There are a thousand different ways to move around, and several qualities of movement. I’m a little sceptical about how people exploit movement nowadays. Before, it was all very traditional. Cunningham or Trisha Brown, for example, had very clear styles, defined spaces in which to explore movement. Today, professionals are looking for a dance that mimics the movements of our daily life. But I’m particularly interested in the gestures that are derived from physical and emotional states, in controlled and uncontrollable movements, that are the outcome of intense emotions.”

Everything is dance?

“No, definitely not. Everything is movement, in the way it is thought, executed and understood.”

In 1994, upon the invitation of S.M.A.K. in Ghent, you participated in a project called This is the Show and the Show is Many Things. What can a show never be? Are there things you absolutely refuse to include in your shows?

“It would be interesting to see what traces remain of my earliest shows in my most recent choreographies. My first choreography in Europe is over twenty years old, I was just 26 years old. Nowadays I’m still interested in vulnerability. I always try to create spaces that raise questions without wanting to provide the answers, or resolving things. But there is one thing that I really don’t like and that is to see dancers who do not inhabit their bodies. Even though movements can be abstract, or ultra-aesthetic, dancers must exude life, must be sensitive. They should not be empty vessels, or bodies that demonstrate something.

We are all placed on earth for each other’s mutual and spontaneous elevation. This is our ultimate goal. So sometimes you need to irritate your audience, to hold up a mirror to them where it hurts. On other occasions, you must propose alternatives. Art has the right to get it wrong, but you cannot get caught up in what is politically correct or stick to traditional approaches. Sometimes the result can be quite perturbing and the spectator may not agree with you.

We all think that we understand the world around us, and this is a very precious sentiment. But I think that we should also try to understand with all our senses, with our nervous system. A voyage is a way of transcending our rational mind. Art is another way of achieving this. Analysing a performance is not enough. You must feel it, let it engage in a dialogue with our subconscious.”

What would you have done if you had not become a choreographer?

“I haven’t a clue. A photographer? A religious fanatic? A homeless person? A psycho? (laughs) I only had two wishes: to travel the world and become a “healer”. But I had no idea whatsoever what this meant!”

List of solos and duets

Inflamável

In Inflamável, Meg Stuart collaborated with costume designer Jean-Paul Lespagnard and performers Vânia Rovisco and Márcio Kerber Canabarro, to create a performance that plays with images of fame, risk and vulnerability. Two bodies writhing through a desolate landscape; a duet on the border of pride and loss, success and decline, disillusionment and the lure of the unattainable.

Inflamável arose as part of The Greatest Show on Earth (2016), a collaboration between the Hamburg Internationales Sommerfestival Kampnagel and Künstlerhaus Mousonturm (Frankfurt am Main).

Concept and choreography Meg Stuart

Created with and performed by Vânia Rovisco, Márcio Kerber Canabarro

Costumes Jean-Paul Lespagnard

Live music les trucs (Charlotte Simon and Toben Piel)

oh yeah huh

In her third evening-length piece No One is Watching (1995), Meg Stuart continued to develop her early practice of distortion and fragmentation. One of her darkest pieces, she staged a scarred love story for six dancers, stripped of any form of tenderness, warmth or intimacy. In this excerpt, Claire Vivianne Sobottke performs a short solo to a soundtrack by Vincent Malstaf. We see a body searching for meaning, confusing intimacy with lust and love with pain.

Choreography Meg Stuart

Performance Claire Vivianne Sobottke

Initially performed by Meg Stuart

Sound design Vincent Malstaf

Dust

In Built to Last, a group piece created in 2012, Meg Stuart works with elements of universalism, timelessness and monumentality, set to a classical and contemporary score. For this excerpt, Maria F. Scaroni used the 1978 video of Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A, produced by Sally Banes, as a starting point. First performed by Rainer in 1966, and since then reinterpreted and reinvented by various dancers and choreographers, the piece is an allusion to how art can survive as a living archive, as a constant work-in-progress.

Choreography Meg Stuart

Created with and performed by Maria F. Scaroni

Live music Jordan Dinsdale, les trucs

Signs of Affection

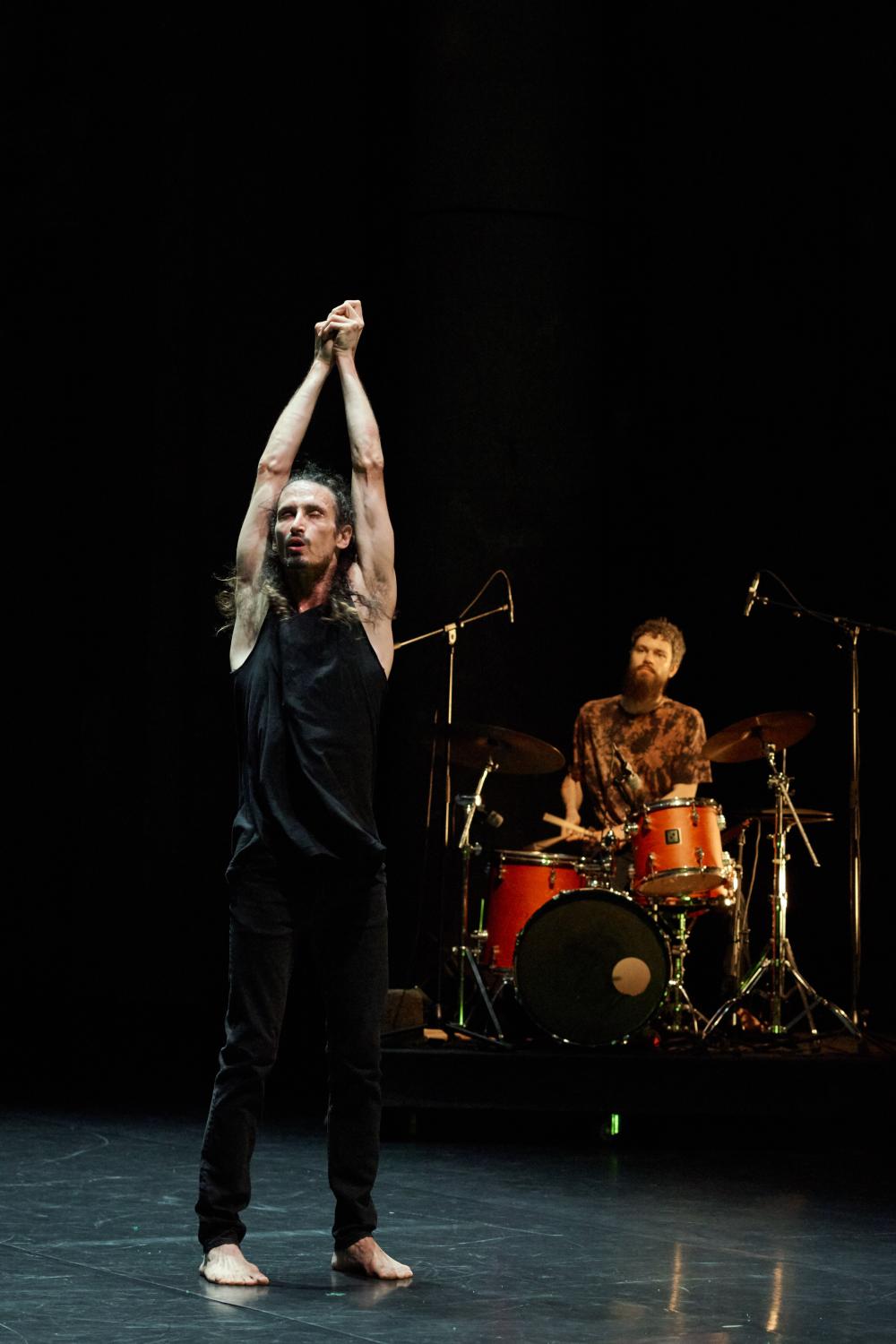

Signs of Affection was created in 2010 within the frame of the ArtCena festival in Rio de Janeiro. After spending time in a studio to research material for VIOLET (2011) and while getting impressions of the city, Meg Stuart made this short solo as an act of erasure and devotion. In a powerful blur of emotions, the intensity of the movements gets framed to the hands and the head. An explosive drum solo partners the performance, which fades out in a series of sensorial sculptures and a resonating silence.

Choreography Meg Stuart

Performance by Márcio Kerber Canabarro

Initially performed by Meg Stuart

Music Brendan Dougherty

Live percussion Jordan Dinsdale

Duet from UNTIL OUR HEARTS STOP

In this excerpt from the 2015 piece UNTIL OUR HEARTS STOP, Maria F. Scaroni and Claire Vivianne Sobottke explore the borders of social contact and touch. In a playful horseplay they exert control over their bodies, their identities and the gaze of the audience, making a statement on womanhood and how their bodies are perceived by others and themselves.

Choreography Meg Stuart

Created with and performed by Maria F. Scaroni, Claire Vivianne Sobottke

Original music Paul Lemp, Marc Lohr

Live music Jordan Dinsdale, les trucs