L'Étang

L'Etang (The Pond) reveals an intricate tale of filial love

An interview by Vincent Théval with Gisèle Vienne. General information about the performance and the credits are to be found here.

What drew you to this text by Robert Walser?

I admire Robert Walser’s writing. It was Klaus Händl, an Austrian writer and director, with whom I have an artistic and personal rapport, who introduced me to this little-known text; in collaboration with Raphael Urweider, in 2014 he translated Der Teich (the Pond) from Swiss German to Standard German. It seemed obvious to me, first of all based on an intuition, to stage this text, a disturbing questioning of feelings, order, disorder, and what constitutes the norm—and the way that this family drama reflects the violence of the social norm inscribed in our bodies.

What did you see in the text, or between the lines, that made you want to adapt it?

It is a play that Walser wrote for his sister, a private text, of which she revealed the existence long after his death. Back then, it presumably never occurred to him that there would come a day that it would be staged, and that this text would become something other than an intimate message addressed to his sister. It is still written with eight scenes, characters, dialogues, and spaces that seem quite real. This theatre piece—which, despite its form, may not actually be one—seems to me rather like the need for a communication too difficult to express in another form. I also read it as a monologue in ten voices, an overwhelming inner experience. The possible space of interpretation and staging, opened up by the text and the subtext offered by this writing, is vertiginous. The plays that stimulate me the most are those that are not obvious to stage, and invite us to question our perception, including through their formal difficulties.

L’Etang is the story of a boy who feels unloved by his mother and, at the highest point of his despair, pretends to commit suicide in order to see her love for him one last time. The text is permeated by a confusion, a very strong adolescent distress and a disconcerting sensuality. We find in L’Etang, as in all of Walser’s work, through humorous, sensitive, and discreetly but frankly subversive writing, questions related to order, rules, respect for them and a reassessment of them. This involves the relationship of the dominated, who always has the central role in his work, to the dominant. The dominated one, apparently wise, is genuinely subversive. He always knows the rules full well, but he turns them around, cannot follow them or, more often, doesn’t want to, and criticizes them by pretending to follow them. The space for reflection that this text opens up to the staging must question the order justified by a norm, the formal one of the theater and of the family. Like a varnished painting that cracks, L’Etang opens out onto the game of abysses and chaos. There is something extremely exhilarating for me to be around these abysses. I love live performance, exploring the present moment of reality in its density, at its most vibrant, the intensification of experience and the emotional experience of time. And being alive is the opposite of being anesthetized in our structures—it’s deeply and genuinely calling both those structures and our perception into question.

How do these issues translate into staging?

By juxtaposing different levels of interpretation, which may even be in tension or contradict each other. By juxtaposing different formal languages, that is to say, different hypotheses for reading the world. By provoking a questioning of the signs deployed at the very heart of the staging and during its development. By undergoing experiences where the body questions reason, by experimenting and provoking flaws and fissures in our reading of the world because, as Bernard Rimé analyzes the issue in his inspiring text “Emotions at the service of Cultural Construction”, “(...) emotions are states that signal flaws in the subject’s anticipation systems, or in other words, in aspects of the subject’s models of how the world works.”

In my staging of L’Etang, to summarize, there are numerous levels of interpretation, three of which are the most readily comprehensible. The first is the story itself as it is read literally. The second, which in my opinion is fairly obvious, hypothesizes a person who imagines, fantasizes, hallucinates this story, in a way which more resembles the experience that Walser himself could have of his text—with a staging that recalls our relationship to the imagination, whose quality and density of impressions, and the perception we have of them, are erratic: certain elements are extremely precise and vivid, while others are fuzzier or even absent. These differences in perception can be visible, noticeable, in a variety of ways on stage, for example by means of different degrees of physical embodiment and disembodiment. Also, through the various treatments of temporalities which is very characteristic in our creation of movement, of music, light, and space, as well as the interpretation of the text, and which in particular convey the sensory perception of time. The different temporalities participate in this layered composition, which allows their formal articulation and the deployment of the experience of the present, between the real and the fantasized, constituted in particular by memory, the past, and the anticipated future.

And then the third level, which is what we see if we don’t follow the conventions of the theater: two actresses in a white box, Adèle Haenel and Ruth Vega Fernandez, who are performing this piece by Robert Walser. It’s always quite surprising to discover that what one accepts as seen in relation to what is seen, is determined by the conventions of reading. In theatre, the gaze is conditioned by our cultural constructions. And this is true outside as well. We know this, and yet putting these constructions into perspective, and deconstructing them, is a complex exercise. Therefore I believe it essential to successfully call our perceptual habits into question. Hoping that the artistic experience, the necessary creation of new forms, and thus of new readings and experiences of the world, can allow us to question and shake up the pseudo-reality, the result of the creation of a shared representation of reality, a social norm.

How did you conceive of the work on sound and music with Stephen O’Malley?

I see music everywhere: in the colors, the lines, the movements, the bodies, the text, the sounds ... And this directly influences my way of staging and choreography. Purely in terms of sound, what we hear first are the amplified voices of Adèle Haenel and Ruth Vega Fernandez, who perform the text in a very intimate fashion through a complex game of dissociation of voices. Adèle acts out the voice and body of Fritz, the boy in the main role, as well as the voices of the other children and adolescents, which seem mute in the way that I represent them. Ruth acts out the voices and bodies of the two mothers, the voice of the father, and occasionally more. They also perform as themselves. This involves a vocal score for 10 voices, performed by two people.

The collaboration with Stephen O’Malley on my works has been going on now for thirteen years. This new collaboration is therefore part of our longstanding artistic dialogue. The composition of music intrinsically follows the process of creation, because in the composition of my pieces the music is put together in a close relationship to the staging, just like space and light. Writing for the stage is for me the articulation of all the media on the stage: all of them are present in a unified construction process from very beginning and evolve during rehearsals. Stephen O’Malley’s original musical compositions, which are very much present throughout the play, also seem to be part of Adèle’s and Ruth’s game, as extensions of their bodies. These musical components, just as much as the original piece composed by François Bonnet, carry a very strong emotional charge; their material is visceral, and the compositions work powerfully with both time and space.

This piece is created in memory of our very dear friend and collaborator, the actress Kerstin Daley Baradel, who died in July 2019, and with whom we had developed this work so intimately.

BIOGRAPHIES

Gisèle Vienne, director

Gisèle Vienne is a franco-austrian artist, choreographer and director. After graduating in Philosophy, she studied at the puppeteering school Ecole Supérieure Nationale des Arts de la Marionnette. She works regularly with the writer Dennis Cooper, among others.

Over the past 20 years, her work has been touring in Europe and regularly performed in Asia and in America, among which, I Apologize (2004), Kindertotenlieder (2007), Jerk (2008), This is how you will disappear (2010), LAST SPRING: A Prequel (2011), The Ventriloquists Convention (2015) in collaboration with Puppentheater Halle and Crowd (2017). In 2020, she created with Etienne Bideau-Rey a fourth version of Showroomdummies at the Rohm Theater Kyoto, originally created in 2001.

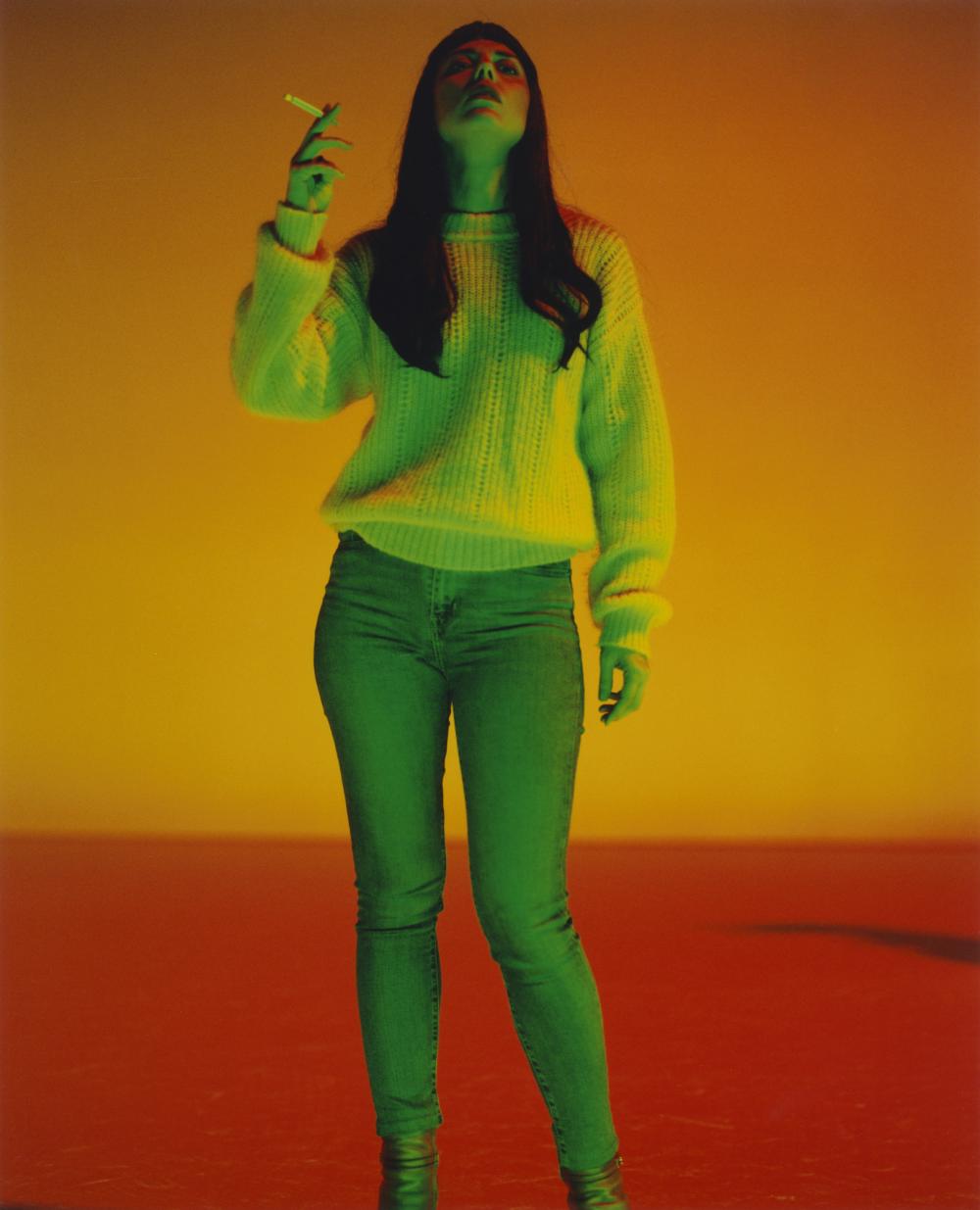

Gisèle Vienne has frequently been exhibiting her photographs in museums among which the New York Whitney Museum, the Centre Pompidou, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires. With Dennis Cooper, Peter Rehberg and Jonathan Capdevielle she published two books : JERK / Through Their Tears and 40 PORTRAITS 2003-2008, in collaboration with Dennis Cooper and Pierre Dourthe in February 2012. Her work has led to various publications and the original music of her shows to several albums.

Her latest show L’Etang (The Pond) based on Robert Walser’s short story Der Teich was created in November 2020 at the TNB in Rennes.

For more information please visit: http:// www.g-v.fr.

Adèle Haenel, in the roles of Fritz and all the other voices.

In 2006, Adèle Haenel starred in Céline Sciamma’s Water Lilies, for which she was nominated for the César Award for Best Female Hope. Since 2010 more roles have followed, varying from collaboration with young film- makers in their directorial debuts to more experienced directors. She performed in L’Apollonide by Bertrand Bonnello, L’homme qu’on aimait trop by André Techiné, Les ogres by Léa Fehner, La fille inconnue by the Dardenne brothers, 120 battements par minutes by Robin Campillo, En liberté by Pierre Salvadori and Portrait de la jeune fille en feu by Céline Sciamma. Many of the films in which she has featured have been shown at the Cannes Festival. In 2014, she won the César for Best Second Female Role for her role in Suzanne by Katell Quillévéré, then in 2015 that of best actress for her part in the film Les combatants by Thomas Cailley. In addition to cinema, she made her theatre debut in 2011 in a staging of La mouette by Arthur Nauzyciel and has since alternated between theatre and cinema projects.

Ruth Vega Fernandez, in the roles of the two mothers.

Born of Spanish parents, Ruth Vega Fernandez grew up between Spain and Sweden, where she trained in dance at the Academy of Dance and at the Royal Opera House in Gothenburg. She arrived in France at the age of 17, after living in the United States. She joined ENSATT (National School of Arts and Theatre Techniques) as the first foreign actress. After graduation, she joined the TNP troupe (Théâtre National Populaire de Lyon) and performed under the direction of Christian Schiaretti for four years.

Back in Sweden, she was given one of the main roles in the Upp Till Kamp aka series - How Soon Is Now (FIPA Gold Award and Prix Italia). She then went on to play leading roles in film, television and theatre. In 2017 she was named best actress in a supporting role for Gentlemen, directed by Mikael Marcimain. Back in France, she created Ivanov with the Extime Company and played the role of Anna Petrovna for three years. In 2013, she created and played in Scenes of the married life with tg STAN, a piece that toured in France and elsewhere until 2016. In 2016 she performed in Cannabis, a series directed by Lucie Borleteau. In 2017 she participated

in Occupation Bastille, a project directed by Tiago Rodrigues at the Théâtre de la Bastille, then acted in Bovary, also directed by Tiago Rodrigues. In 2019 and 2020 she also performed in The Prodigious Friend at the National Theater in Stockholm, Sweden.