Akal

We are together in a place that we don’t own

An interview by Elias D’hollander with Radouan Mriziga, for DESINGEL. More information on the performance, playdates and credits are to be found here.

Can you use choreography to fill in the gaps in our historical memory? In Akal, the final part of his latest trilogy, Radouan Mriziga once again focuses on the knowledge of the Imazighen, the indigenous people of North Africa. Elias D'hollander in conversation with Radouan Mriziga.

Elias D’hollander: We share this fascination with movement and architecture which is an important underlying thread in your work. Where did this come from?

Radouan Mriziga: Architecture is one of the first arts we encounter and are influenced by. It helps us construct certain ways of seeing space, of seeing colours and light and is free for everyone to experience. Even when a building is an institution, it is never institutional itself since you experience it being part of the city. Looking at geometry and landscapes, something began to become clear to me: body and architecture are intimately connected. So in my dance studies I always kept a natural curiosity to this direct relation to the surrounding. Since this approach is precisely the basic definition of choreography, designing space and time for bodies, it made sense to use the knowledge closest to me, a fascination to architecture, and to go in different directions like using poetry and text as an extension of this basic relation.

ED: Why was it important to work on this?

RM: I would not say that it was about having to, but that it came naturally. From my childhood I had this fascination with geometry and arts anyway, so it very naturally became a tool to serve a more complex relation to society in general. It was itself the question: what is the impact of your gesture? This is exactly where my thinking about sharing and constructing space, comes from. It emerged from an allure to construct a questioning of this impact of the gesture through my body, through the space around me, through language, through the audience and society, with someone else. This starting from the centre and expanding outwards happens to be a concept in Islamic geometry as well.

ED: This becomes an almost ecological question?

RM: That is why I am fascinated with geometry: it is a point of departure that can grow to become very complex by connecting to other points to construct a whole structure. I like this phrase we use in 0.Extracity: “Construction is the process of making visible what was invisible.” Space is not only what we see, it’s not linear, just like time is not linear. It is much more inclusive. When you think of space as an imagination, it seems to be about being collective, about feeling each other in different places. Philosophically there is no escaping the fact that we share this space. The awareness of this ecology of space directly impacts our relation to what is shared and gives rise to our ecology as a globe, of our thinking together. It becomes about how to distribute everything equally: space, wealth, power, knowledge.

ED: So the relation to architecture as a tool to think about what happens between people?

RM: Yes, and always with an ephemeral architecture, a mix with concrete constructions and imaginary spaces. We share this door for example, but when I add text, maybe it becomes a door to a bottle garden. We now share this image and neither you nor I can keep it only to ourselves. Contrary to having your own place, we have this space together, without effort. We are together somewhere that we don’t own. I think that’s a beautiful poetry of space. I hope this gesture can impact the people that become part of my work, that we share something but don’t own it individually. It only exists because we share it.

ED: Is that where the use of tape and chalk comes from? As building blocks of shared architecture?

RM: Of course they are a very practical choice as well, but they do have a beautiful quality of creating space with the simplest tool you can have. Like when we used to draw spaces on the floor when we were kids and they would become a house. You experience the making of space as well as the impact of this creating. Thus these two tools, bring the curiosity of the child, the possibility of making a gesture, rethinking, doubting and then erasing it if it’s not the right one at that moment. In this way my work is never about creating monuments. This is where architecture becomes detached from the body and instead represents a kind of power, which is always going to be wrong. Because one day this power will be questioned and become alien. These more ephemeral materials allow for space to keep a deep harmony with time.

ED: This feels like a different approach than for example Tafukt, where space seems to be less ephemeral. How do you experience this difference?

RM: It’s not so different in the end, the creation of space is just more visible in three dimensions, but remains technically very simple: foils, cardboard and plastic. In this new trilogy, I’m working on time and how to rethink the space of history. How to share and question it and how to not speak about it in the linearity of time with events that, like monuments in architecture, belong to one power and one moment in time. So it’s precisely because the time I play with is not linear that we needed to clarify some directions. Three dimensional pace is a useful tool for this, since it can hold different layers of meaning, literally and symbolically, as a volume of meaning. The structure in Ayur, for example, is a geodome of recycled cardboard and plastic. It evokes the moon, to which Tanith, the goddess we are working with is connected. She is also represented by the Amazigh, the indigenous people of North Africa, by the triangle, the basic shape of the geodome. It refers even to Star Wars, since the makers used the architecture of Tattooine, an actual city in Tunis, in the film, but didn’t credit. So when I work on space, it’s time that guides us, where space remains fluid, so we can stay together. While in this trilogy it’s the opposite. A more defined space gives more freedom to time.

ED: The way you made the geodome also holds complexity: perishable cardboard, easily disassembled, yet, architecturally, the triangle is the strongest shape?

RM: This is exactly how I feel about it. You start from triangles and place them in a very precise way so they hold each other but when there is a mistake, the structure falls. It was really about how to build with this fragility. Tom, an architect, somehow engineered the dome, but sometimes it still falls and we need to hold it up with threads. This to me is very symbolic of the concept itself. The strength of the triangle somehow softens by choice of material and the possibility of mistakes and becomes something that will be impacted by time. This brings again the idea of chalk and tape, of time as part of the structure, being able to easily take it away. You feel time as being with you, in space, all the time. In a strong structure, we are in space, without time.

ED: You work here on three goddesses who all share the same roots, historically. Why this decision to chronologically go back from the youngest, Athena, through Tanith, to Neith, the oldest?

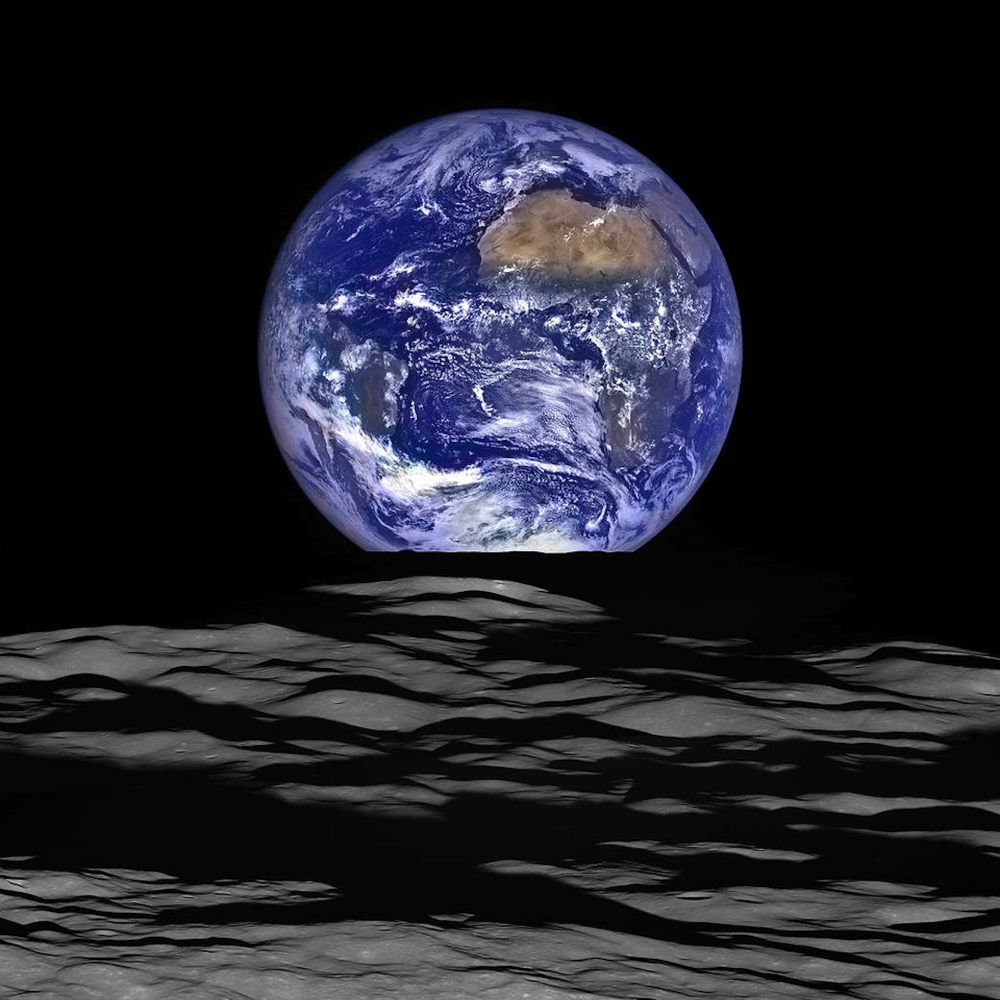

RM: Because of this question of how we can talk about history. There is always the tendency to go forward, to pass and think we surpassed history. The holocaust and colonialism are finished, now we are somewhere else. But their impact remains and we have to constantly find ways to relate to it. To accept that it shaped our present and think about how it might shape our future. This chronology is not to reverse linear history, but because the goddesses are actually one. They just have different names. Neith, the creator of the world, is connected with earth. Tanith is related to the moon and Athena to the sun. So there is this movement in the trilogy, to go from the sun, closer to the earth, to Neith. So to go back is to say that we are going towards it, that they never left.

ED: and life which is only possible with the perfect relation of sun, moon and earth.

RM: Exactly

ED: Your new project is called Libya, the birth place of Neith. What can you tell us about this work?

RM: I start from the point where the Sahara was a forest, as a way to pass through different points in time, from Libya and North Africa, to the Mediterranean, the Arabs and the French, to, hopefully, a better future. A whole look at history through the elements that the Amazigh kept their history with: art, language and space. Libya was the name of the entire Amazigh region, but through colonialism it became isolated. But only when you talk about space as separation. When you look at the Amazigh as history, it becomes clear that you cannot avoid their intertwinedness. In this same way the Mediterranean becomes a much more fluid space. It’s again this geometry that allows complexity, so that it doesn’t make sense anymore to look at history from only one perspective. Suddenly the idea of collectiveness reappears. From positive to catastrophic, we have to be aware that we share it and not look at it not through archives and monuments, but see how things are related. Again, to start from your own body, through your history to someone else, from ancestors to metaphysics, to being together. Growing to become once more this one, shared, thing. In space.