| ma | di | wo | do | vr | za | zo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

20

|

21

|

|

22

|

23

|

24

|

25

|

26

|

27

|

28

|

|

29

|

30

|

31

|

|

|

|

|

Lees meer – Somewhere at the beginning

Lees het online programmablad van Somewhere at the beginning

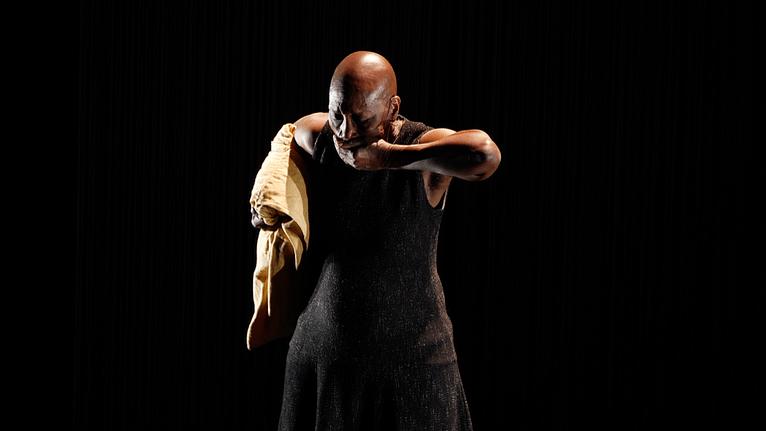

A COMMENT BY THE DIRECTOR MIKAËL SERRE

(May 2015)

I vividly remember a remark that Germaine Acogny made at our first encounter: “My life has often been unsettled. I come from somewhere, but when I try to distance myself I cannot escape from my past. It’s as if I go back to the beginning – the place from whence I come – back to my ancestors and those who accompany me.”

These words speak of an action: the exploration of contrary forces. It is an upward compulsion, but also a gesture of acceptance of the force of destiny.

Germaine Acogny told me her story – that of her family and its conflicts, of her host country Senegal , her time of ‘exile’ in Europe and her return to her native Africa. Before we met she told me that in her next work she wanted to think in terms of Greek tragedy. That seemed to me to be most appropriate. When I read the text of a play I hear the moments of ecstasy, doubt and desert crossing. When we met I heard Shango: the god of thunder, lightening and war. I questioned my wish to mix the daunting problems and towering figures of Greek tragedy with the history of Africa. I decided that this project would fulfil the need for a confrontation between the self and the world.

YOU KNOW WHERE YOU WERE BORN, BUT NOT WHERE YOU WILL DIE! (Tiviglititi, the sage, ‘Tales of Aloopho’)

In the course of our discussions Germaine often spoke of her grandmother Aloopho, who was a priestess from Dahomey, mother of the sacred and of strength. By reading the ‘Tales of Aloopho’ I immediately saw the connection between these tragic, archaic and prophetic words and the suffering that suffuses the great female figures in Greek tragedy. The story of Medea is that of each member of the audience who looks inward in search of the self. It is the tragedy of truth. It is the ultimate recognition of the self – of a solitude in confrontation with the world.

ON TRAGEDY...

To take a step back, I cannot help thinking of this saying of Tiviglititi in one of Germaine’s grandmother’s many stories. In the village only the most exceptional of men could become king. They were not born there, but had given evidence of their wisdom elsewhere. What a suggestion when we consider the crises of identity throughout Europe nowadays! Should we not say – as I recently read on a scrap of paper stuck on the wall of the Maxim Gorki Theatre – that identities are a means of transport and not the end of the line? This is also evidenced by the book written by Togoun Servais Acogny – Germaine’s father – which she lent to me to help with my research. It is the moving testimony of a man who from childhood was recommended to deny his past in order to be ‘civilised’ by his contact with Whites.

‘I remember that there were some large copper knives at home. They were there during my childhood, then they disappeared. One day when my father was old and sick I visited him in Paris. Once again I saw those knives – those of my childhood...

...HERE’S TO LIFE!

What Germaine shows through her testimony and her dance, translated into movement, breath, is as if a new start is still possible. It goes through a struggle of the mind against itself, through a revolution capable of designing the inexistent. At a time where the great ideologies no longer manage to provide an identity to the individual, it is essential to continue to offer a dialogue with the intimacy of everyone. It is a testimony on stage in the analysis of breath and movement, a face to face between a loneliness on stage and the intimacy of each spectator.

HERE’S TO LIFE!

If a jump ahead were possible it would land amid spiritual turmoil. Germaine represents what almost all of us have become – human beings in transit, exiles, the converted and the reconverted, people who lose themselves and find themselves again. Ultimately identity is not an conclusion but a process. How many Europeans (people?) do not adapt, do not wish to or cannot adapt to this continent (of Africa)? It remains to be seen how we have become what we are and what we want to be in the future.

A dialogue between the Occident and Africa is to discover the knot within the body and the sand in the eyes as we confront the narrative of the modern world.

Rehearsals began at Toubab Dialaw in Senegal. It was my first encounter with this country and continent. Germaine Acogny introduced me to its history, which I decided to tell in an intimate manner. It is perhaps the only way to avoid all manner of ideologies with their hotch-potch of simplifications.

This passion is also a tenderness that I felt during rehearsals and as I questioned myself whether I had the right to handle Germaine’s personal history, which comprises deficiency and betrayal that echoes general history. It was a journey into the interplay of memory and forgetfulness. Since family history brings back memories of images, odours, feelings and sounds it was essential to work in close collaboration with the video artist Sébastien Dupouey, the lighting specialist Sébastien Michaud and the musician and composer Fabrice Bouillon ‘LaForest’, who used their art to create a dialogue between the past and the present. Naturally one speaks of wounds on the stage, but also of how we as artists to a certain extent can, each in our individual way, bring about an assuagement without effacing the past. Giving this story a materiality is to challenge the act of forgetting without acrimony and to mourn our structuring myths, whether recycled or still alive.