How Are We Many?

text by Samah Hijawi

For the opening essay of Kaaitheater's sep-dec pocket, we asked artist Samah Hijawi to dive deeper in the question 'How to Be Many?'

When I got invited to write this piece, the first thought that came to my mind was rather than to question How to be many? I immediately had the urge to rephrase it as How are we many? From this small rephrasing, we can affirmatively assume a plurality already exists in our lives. We do not have to start from scratch, or relearn a new way of living, but rather build on what we already have. That is not to deny that the human story is entrenched with hierarchies that have created inequalities both intra-species and inter-species. Undoubtedly, the narrative we have been operating with places the white man (and all he has constructed in spiritual and financial systems, science, and technologies) above all beings —and non-beings. In my project Kitchen. Table., which explores the history of food and food-making practices through trade and migration, I found that a different story already exists in the feminine spaces and practices in the kitchen.

We all need to eat and most of us eat not only for sustenance, but for the joy of taste and for the conviviality of sharing a meal. The taste buds in our mouth that bring us pleasure, and the idea that what we eat is ‘good for our body’, are deeply entrenched characteristics that drive us to make choices on what food we cook or eat. We need to think like Robin Wall Kimmerer, who says in her brilliant book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants: ‘Imagination is one of our most powerful tools. What we imagine, we can become.’ What Kimmerer writes about are stories of re-worldling that paint a different image of how we can co-habit with other beings and non-beings on earth, and beyond it into the cosmos.

Take Time, Listen to Your Gut Feelings

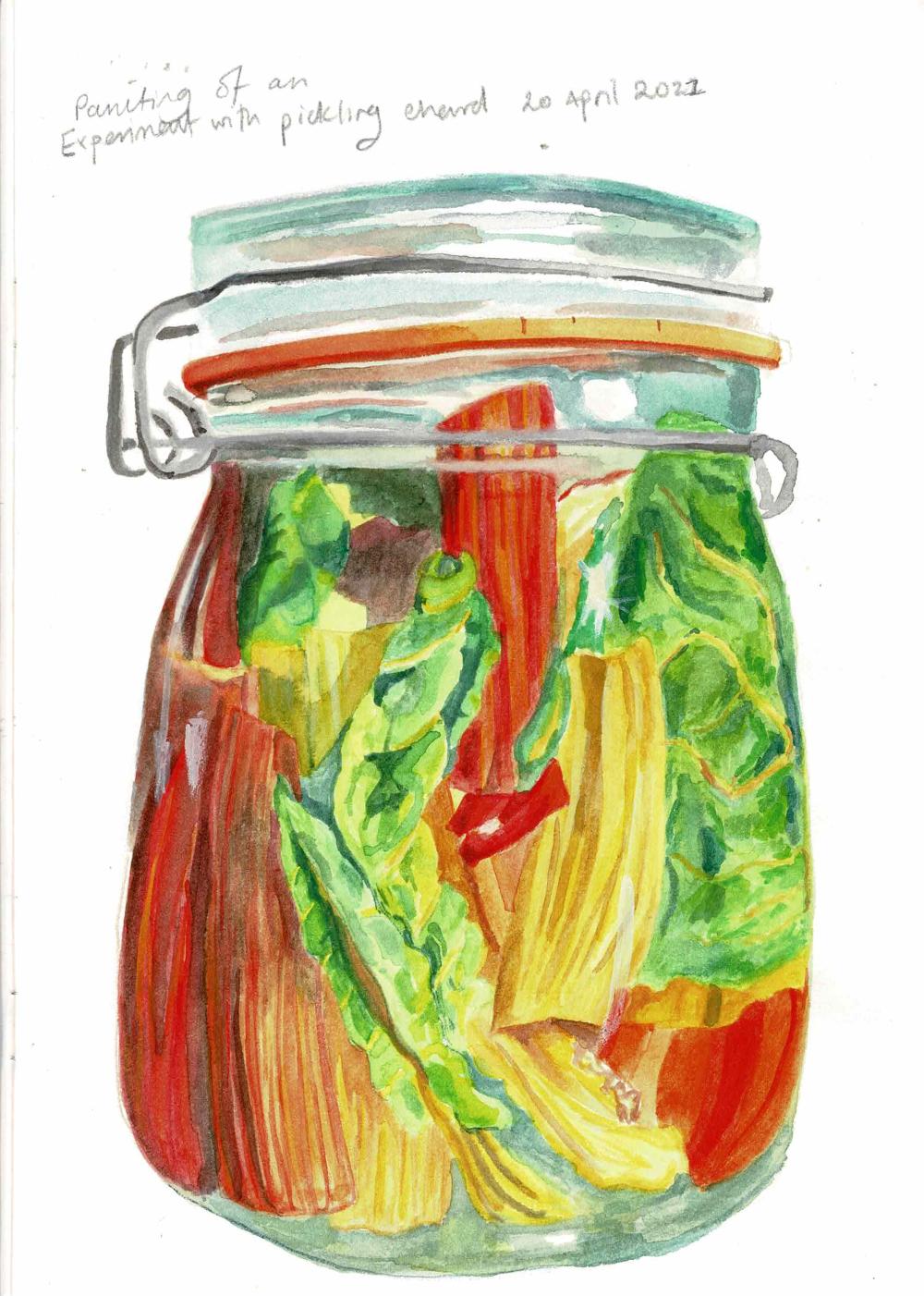

The kitchen needs time, and making food is often a collaborative process in one way or another. Pickling/fermenting is a metaphor for both these ideas, so I invite you here to make this simple pickle at home. The pickling/fermenting process essentially creates the conditions for yeast and bacteria to form a community in a jar of vegetables. As my artist friend Mirna Bamyeh puts it: you are hosting other micro-organisms who actually do all the work! The preparation itself doesn’t need much time, but the fermentation process does.

Jar Find a glass jar with a screw top, or a Mason jar. Make sure it is clean (hot water, soap and/or vinegar does the trick), then dry. Veggie You can make this pickle with one vegetable, or a mixture of these three: Wash and break half a cauliflower into little florets. Wash a carrot and a medium-sized beet; if you buy these organic, you can wash them well and not peel their skin. Cut into bite-sized pieces. Put all three in the jar.

Brine Dissolve one generous tablespoon of salt in 2 cups (about 500ml) of warm water. The brine must cover the vegetables completely. There should not be any space at the top of the jar, otherwise the air will invite fungus — which is not welcome to this party! So, if you need more brine, make more.

Flavour If you are feeling adventurous you can add chili, or peppercorns, or a piece of garlic, or a sprig of a fresh herb such as laurel or rosemary.

Time For one or two days, the jar can sit on a windowsill on which the sun shines directly. This gives you the chance to admire the beautiful colours of the jar, while the warmth gets the fermentation process started. Then store in a cupboard. It will be ready to eat in about three weeks

In the meantime, I invite you to imagine the larger community of people in the city who have the same jar of pickles sitting in their window. I also invite you to research the human microbiome, and become acquainted with the many bacteria, fungi, and yeasts that live in and on our bodies. Some of these bacteria and yeasts from our skin (and vegetable skin) are busy fermenting the vegetables in the jar. These communities make the unique flavour of the pickles. When you open the jar to taste the pickles, you are feeding the bacteria and yeast communities in your mouth and they help you break down and digest the food. It is a reciprocal relationship. There are over 30 trillion micrograms of bacteria living with us in our bodies, and they outnumber human cells by 10 to 1. Therefore, we are many, or maybe we are not human at all!

Tracing the Lifeline of a Plant

Coming to live in Belgium nine years ago made the Kitchen. Table. project possible. The social fabric in different cities in Belgium—especially Brussels—offers a richness of food cultures from all around the world. I was not exposed to this when I was living in Jordan, where food is predominantly from the Eastern Mediterranean. Diverse food cultures in a city are first and foremost evidence of the diversity of its residents. Migrants bring with them the ingredients they need to cook their food. Supermarkets start to open up—enterprises that are supported by a global network of trade. Soon after, restaurants will surely follow. And before you know it, the most popular items on the menu have made their way to becoming everyday commodities on the supermarket shelf. Humous is a good example of this story. A recipe of this humble ‘street’ food of the Arab Mediterranean first appears in the fourteenth-century cookbook The Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety of Food on the Table, written by an anonymous author in Egypt. In its modern translation by the brilliant academic and cook Nawal Nasrallah, the book lists eleven different recipes of Himmas Kissa. Below is one you can try: (618)

Another recipe for [Himmas Kassa] Take boiled chickpeas and pound them into a fine mush. Add vinegar, sweet olive oil, tahini, black pepper, mint, flatleaf parsley, and a bit of dried thyme, walnuts, almonds, pistachios, and hazelnuts-all pounded, toasted caraway and coriander seeds, salt, lemon preserved in salt, and olives. Spread the mix on a plate. Sprinkle the surface with cassia (cinnamon) and drizzle it with olive oil. Set is aside for a day, and serve it. It will come out good, God willing.

While we struggle today with the negative consequences of our appetite for both the familiar and the unknown, imported produce gives us another way of understanding our connectedness beyond political borders. When we buy sesame seeds harvested in Sudan, we are consuming a plant that formed its life from another earth, air, rain; it endured (dust) storms, draughts, and floods. It shared its life with worms, it fed on animal poop, and mingled with yeasts, fungi and bacteria, as well as the humans that harvested the seeds under the blazing sun. It’s true that a lot of these products have been cleaned and ‘sanitised’. Nevertheless, by thinking of the singular journey of a plant — even metaphorically — we can give tribute to all the lives we eat (not just the animals) whose happy or unhappy journey ends up in our belly, feeding our body, and the trillion other bodies living in it. In the smallest grain of sesame we consume we become Sudan.

In his book Fruit from the Sands: The Silk Road Origins of the Foods We Eat, Robert N. Spengler III outlines the history of one of the most famous trade routes in the world which ran from China through Central Asia to what we now call the Middle East. Across this network ‘the transmission of intellectual culture, technology, raw and crafted materials, and human DNA through the mountains, valleys and deserts of the Silk Road shaped European and Asian history… [It] altered ecosystems and cuisines around the globe.’ When we walk into a speciality shop that sells food from Pakistan, Syria, Brazil, Romania or Congo, we are participating in the very old human habit of insourcing and trading products, produce for our joy and sustenance. Humans have always been on the move, and that is how seeds and recipes moved. Let us not forget that 500 years ago there was no tomato outside of the Americas, and garlic has only recently been accepted in Northwestern Europe as a basic herb in the kitchen.

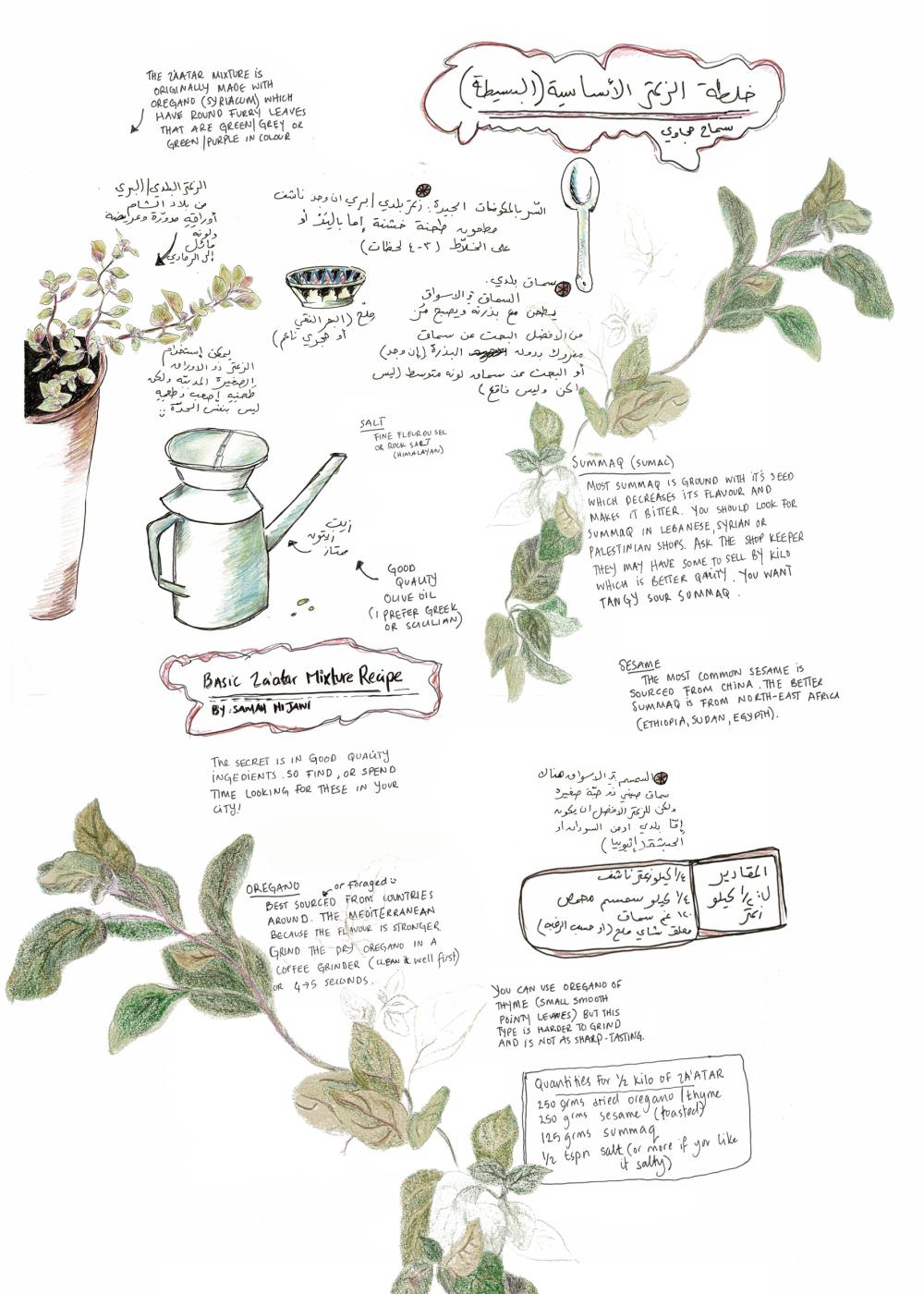

Mighty Oregano

Kitchen. Table. was guided by the three plants that make the herbal mixture za’atar. This food which carries the same name of the plant za’atar—‘oregano’ in Latin and English—is a staple in the Arab Eastern Mediterranean kitchen. It is an everyday food consumed by dipping bread into olive oil, and then into the za’atar mixture, and eating it. Or it is sprinkled on a small freshly-baked pizza called Man’oushe Za’atar.

It strikes me how ephemeral za’atar is—simply a combination of a dried herb, a tiny seed, sesame, and the soft citrusy skin of the seeds of the flower of the sumac tree. Like dust: if you sprinkle it in the wind, it disappears. Not much food from anywhere around the world that I can think of can blow away like dust in the wind. At the same time, it carries so much cultural weight, memory, and a connectedness to the three seasons of the year. In spring, people would traditionally forage za’atar from the wild. In summer, they harvest sesame seeds. And in the fall, they collect sumac.

In Arabic, a single shrub of za’atar/oregano is referred to as beit za’atar, which means home of oregano. Language gives us clues to how people relate to the objects and beings around them. The intimacy of calling a singular bush a home denotes that people recognise the plant as a safe space: a place where beings come together, a place of nurture and care. In the book Gewürze und Kräuter 2, the ‘mighty oregano’ is described as important in medicine for its strong antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal oils. In the past, rather than isolating single compounds in a plant, medics would regard the healing qualities of the whole plant. They also took inspiration from the plant’s form and shape, to understand what we spiritually learn from it. The way a beit za’atar grows—horizontally spreading new branches to set roots beside its mother—signifies strong familial bonds and love. The ‘mighty oregano’ is also connected to the planet Venus. Commonly referred to as the planet of love, Venus guides us in making bonds with people with whom we share a part of our life.

If one bite of food connects us with the many cosmologies of our known and unknown universes, then we are many. We are many beings and non-beings all mushed up in one. I leave here the recipe for making za’atar this fall. The sharp oils of oregano will surely protect your health as the season shifts.

Za’tar Recipe

1 PART DRY OREGANO You can experiment with any oregano that comes your way. The best ones I have come across are either sold in Syrian shops, or in Greek shops under the name Dittany or Dictamnus which have a large, round olive-green leaf.

1 PART TOASTED SESAME or a little more if you like its taste. The best comes from East Africa – Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia.

½ PART SUMMAC Which you can buy from Syrian, Lebanese or Turkish shops in Brussels.

½ TEASPOON SALT Put the oregano in a coffee mixer and grind to the count of 6 or until it’s a lightly grainy powder.

Put it in a bowl with the sesame, salt and sumac. Mix very well so the ingredients blend. Store in a jar in dry place. To eat, put the mixture in a bowl.

Put olive oil in another bowl. Tear a piece of bite-size bread. Dip the bread (with gusto and determination) into the oil. Then dip it into the Za’tar, and then into your mouth!

text & illustration by Samah Hijawi, July 2023.

Samah Hijawi (she/her) is a multi-media artist: a painter, a performer, an astrologer, a storyteller, a researcher, an academic and a cook. Hijawi performed Holy Cow and the Pomegranate: Sumac at De Kriekelaar on October 17th and 18th 2023.