Slovakia, What’s the Story, Mum?

Pour notre saison 25 de janvier-juin, Katja Dreyer a écrit un essai dans le cadre de la ligne de programme How To Be Many Mothers ? Cet essai est une réflexion sur sa performance Slovakia, What's the Story, Mum ? qu'elle présente au Kaaistudios les 26, 27 et 28 février 2025.

Dear Reader,

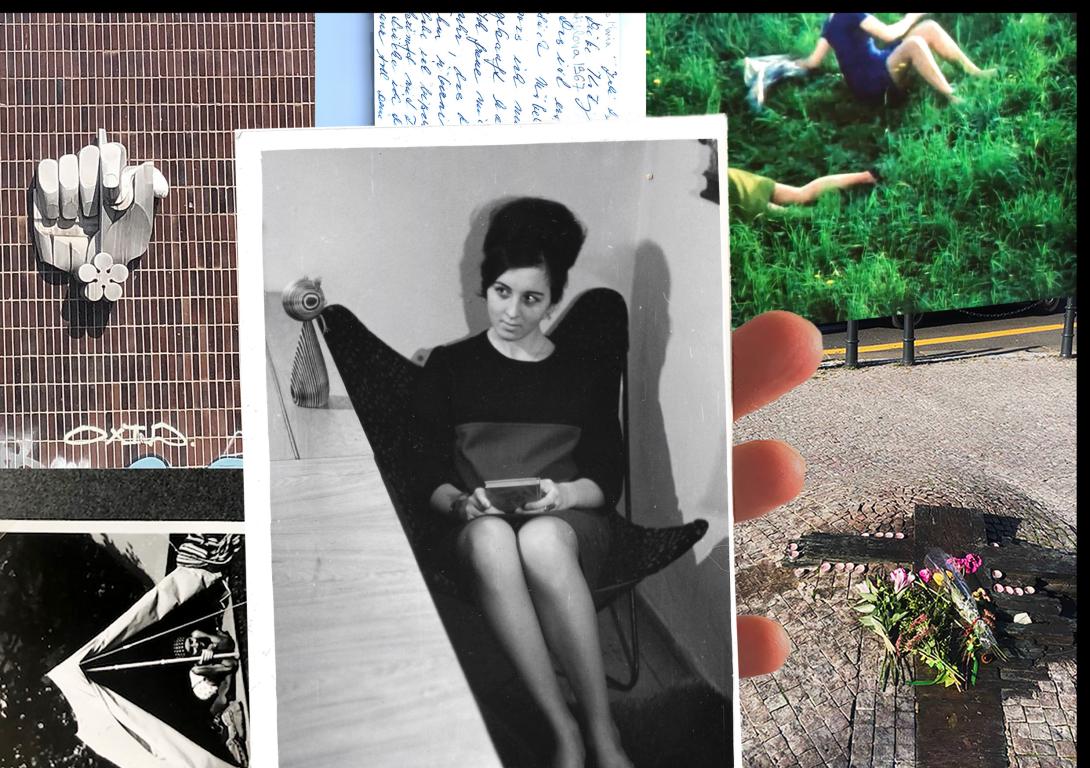

If you have seen any of my shows, then you know they always deal with aspects of German history. That’s my father’s side. His language is my mother tongue – it’s not my mother’s mother tongue. It’s not the language I write in usually, but it’s the language I try to use as a mother, in the hope that my son will have it at hand and in his heart and in his mouth, if needed. At around the same time that I was leaving the age when biological motherhood was possible for me, wondering how my mother had experienced this shift. I felt a strong need to make a work that would help me understand where she really comes from.

Hearing her language makes me vulnerable and restless. I become like a junkie; I want to hear more, then get frustrated because I don’t understand what is being said. I feel embarrassed because I don’t understand and ashamed because I greedily want to hear more. I feel excluded. Maybe the little person in me wants to respect her choice not to pass on her language. Why not just learn Slovak? It’s not that easy....

I could have taken a 6-week intensive language course in Bratislava. A crash course like that would turn me into a Slovak-speaking and -understanding woman. Why cling to an identity of someone that doesn’t understand her mother’s mother tongue? Out of fear of lifting the veil of mystery that hangs over that country without language? A violent rebirth into a world with one mystery less?

I met Peter during the first lockdown, after one of the few shows that were happening. No one wanted to go home. We chatted.I realized he was of Slovak nationality.

Would you be interested to collaborate...a show…on Slovakia? Socialism with friendly face? Language? Prague Spring? My mother?Can you be my Slovak Mum, guiding me through the country?

I blushed while asking – the question felt big, felt like a betrayal. I already have a Slovak mother. Words have power, don’t they? If you use them carelessly, they lose their power. I can give you my word on that! You do not want the word mother to lose its power. He said yes.

A dream coming true. Working in Slovakia.

Dear Katja,

I am sorry for my silence – since I am mothering, I am not so fast with answering emails. But yes, we have an apartment to host you, and we are looking forward to welcoming you here in Stanica-Zilina. Unfortunately, I will not be able to welcome you on Sunday evening, for the above- mentioned reasons. Come to the venue – one of our volunteers will be there with the key.

Bashka 1

I arrive in Zilina in the evening. It’s hot. I had already dragged my too-full suitcase through half of Central Europe that day. It had travelled with me to the airport early in the morning, in the belly of the plane, after some negotiations of its weight, in a bus on the seat next to me, crossing the border from Austria to Slovakia, ear witnessing a fight about agendas between a couple sitting in front of us. She was Slovak, he was American. ‘I cannot read your mind, talk to me’, she said to him, a statement that seemed to puzzle him. Then a three-hour train ride, direction Polish border, in a train with defective air conditioning. A giant nun, fainting from the heat after she has taken off her holy shoes to replace them with sandals. We pass through towns I’ve never heard of, and towns I knew from childhood memories. I suck up the sounds. Next stop, Zilina.

Heavy suitcase, heat, deep flight of stairs, no bus to go to the venue at this hour. Loss geht’s, I say to myself, the suitcase standing next to me. I walk, drag, pull, lift, push. The suitcase is heavy, I am strong. Its wheels are noisy, but they help. We pass squares with churches, go through tiny streets, past shopping malls, abandoned cultural centres, through socialist living blocks, and arrive at the edge of the city, by the motorway. Cars going in both directions. On the other side of the motorway, I see an old railway station house. I hear techno beats coming from there. That must be where I should go.

Writing and mothering: Some thoughts on mothers and stories.

Motherhood comes in different forms. Since I gave birth to a biological child, my understanding of motherhood feeds from that experience. Before motherhood there is pregnancy, an inner- and inter-body spatial negotiation of the one growing and the one hosting and nurturing. Two entities, one inside of the other, expanding. Don’t stand in the way!

Being a biological mother is a unique bond, but it does not guarantee any feeling of closeness. I know that, at times, my mother was afraid of me, not only afraid for me. I am part of her story, her story shapes me, and I shape hers. I grew inside of her, took my space. She gave birth to me, and I, while being born, gave birth to her as a mother.

She never talks much about personal things, but she told me that she was very glad about the presence of a Czech nurse during my birth in Berlin. She could huff, puff, and scream in Slovak and was understood. My dad was reading Der Spiegel, not knowing how to be of support, other than not getting in the way. He did what he could while his partner laboured herself into becoming my Mum.

Around the same time that I started the research for Slovakia -What’s the Story, Mum? I was offered a teaching position at LUCA Drama, in the ‘Writing for Performance’ department. Me? Okay… How to teach… writing? So many ways of writing.

I start by listening. I sit; sometimes I walk. I read, I feed myself with the words of others. I write with pen, paper, on a phone, a computer. I follow the words, till words become sentences, and sentences stories. So much to be discovered. I write, to understand and to be able to share. This process needs space, time, and trust.

As a mother I listen, I tell, I clean, I wash, I shop, I chop, I cook, and I clean again. I hold the space for the child to grow. I look, touch, listen. I establish boundaries, ask for respect. Silence helps. In silence I hear clearly. Silence is a space. A space for secrets, helplessness, power, empowerment; of warmth, cold, horror, and joy; connection, respect, understanding, and separation. How many words for silence do I know? Silence and words go well together.

Silence holds space like mothers do.

Other realities

I meet Bashka at the venue. That place on the other side of the motorway, where old apple trees grow next to a new permaculture garden, where a self-built skate ramp is sheltered by another motorway bridge. There are still trains stopping and departing, vintage one-wagon trains with names like Marienka, Little Monica, Suzka.

I had expected her, just starting this ‘mothering thing’, to bring a baby along. The girl that is with her must be about two and a half years old. Meli, as she introduces her, is looking at me with big dark eyes, clinging to Bashka’s legs. During our residency week we meet several times. Meli always comes along.

She is a foster child and had a troubled start in the world. She cannot go to kindergarten, yet.

I see her curiously exploring every speck of dust; looking for freedom, demanding support, fearing dark corners, and being irresistibly attracted by them, balancing on the frustrating edge of language. The words her foster mother speaks to her are precisely chosen. They mirror back, they do not correct – ‘Meli understands and can correct herself’. Not that I understand – they speak Slovak – but Bashka translates.

I write down everything that I observe, everything that happens. I take pictures of her room in the orphanage, the hospital, write down dates, names of doctors, nurses, small details. She needs to know her story.

We speak about the situation in Slovakia: democracy is being dismantled rapidly, people are leaving – especially people with children. The people who are leaving now were born at the end of socialism. They saw the country changing, for the better and the worse. They returned, and now they want to leave again, for the sake of their children. If we all leave, these idiots can do what they want. I look at her looking at Meli, fishing a slice of orange out of her water glass, examining it before putting it in her mouth. The taste of the orange changes the expression on her face, on Bashka’s face, on my face.

To ‘mother’ is a verb. My mother left her country of birth to look for a life without fear. Slovakia, what’s the story, Mum? is an attempt to find the words to understand and share. To all stories told.

1 Barbora Jombíková, My Contact person at Stanica-Zilina, Nova Synagoga. Dramaturgy, Programmation, Guests.