Social Sculpting

by Elize Mazadiego

Performance and potentiality in social engagement

by Elize Mazadiego

Recently Jonah Westerman characterized Performance as “a term at odds with itself”, referring to the singular designation for a diverse set of artistic practices with their own trajectories, histories and form. Reviving the seemingly eternal ontological questioning of Performance, Westerman reminds us that the parameters of Performance remain porous, fluid and, at times, problematically unclear.

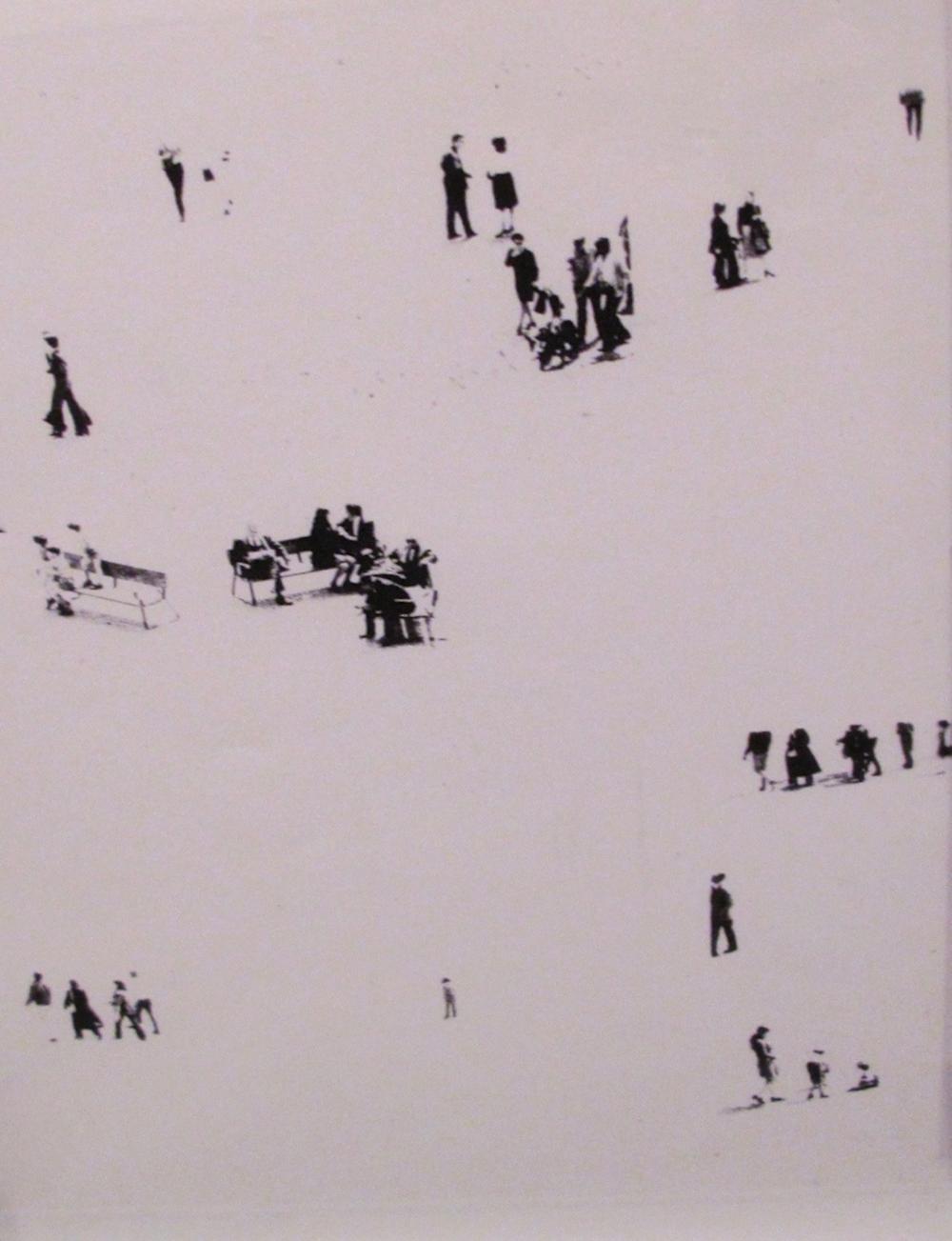

For Performatik 17, the latest edition of Brussels’ Biennial of Performance Art, the variability of the genre was conspicuous. From the many artists comfortably working at the intersection of dance, theatre and the visual arts, to their mutable works and the range of sites in which they were presented, this is perhaps the one unchanging aspect to the widening field of Performance, and more specifically Performatik’s program over the years. What then can be said of Performance in 2017? The biennial offers its own proposal with a turn to “bodily attempts at social sculpting.” This subtitle and curatorial frame emphasizes the increasing phenomenon in performance of exploring the social, and the centrality of the body in its imaginary. A notable proliferation of artistic production over the last fifteen years has sought to engage the social world and its issues. Known under various nomenclatures, notably socially-engaged art or theatre, community-based art, dialogic art, or applied drama, these diverse practices share a new approach to artistic production that involves the staging of intersubjective exchange. This trend gained significant traction following Nicolas Bourriaud’s observation of a transition in contemporary art towards a “relational aesthetic” defined by moments of collaboration, encounters, events between people. Performatik’s call to produce artworks that effectively “create something together in the here and now” certainly resonates with this social turn, echoing the desire to imagine systems of collectivity that go against the grain of neoliberal, individuated, autonomous models combined with digital technology’s reshaping of social relations and community. Performance in particular is perhaps one field that poses a particular sensitivity to the function of social interaction and foregrounds it as an embodied experience. As Shannon Jackson emphasizes, “ensemble” is a dimension of performance that lends itself to coordinating and sustaining human collaboration. Furthermore, the body, and its particular function in performance as medium, serves as the central site of the social that is live, present, and visceral.

Performatik’s specific use of the term “Social Sculpting” evokes Joseph Beuy’s artistic practice when in the 1970s he coined social sculpture as a way to “mold and shape the world in which we live.” It was in the plastic suppleness of his sculptures in the process of their making and in the collective nature of his performances that he saw the creative capacity for art to form society. In “I Am Searching For Field Character” Beuys expands the definition of the artist to include “every living person becomes a creator, a sculptor, an architect of the social organism [as a work of art].” Beuy’s term reminds us that contemporary social practice is built on a long tradition of radical, interdisciplinary art forms of social address. But rather than assume Beuys’ political task to produce art that achieves direct social change, today’s artist adopt his position that art can be a platform for social engagement. In the frame of Performatik, social sculpting similarly expands on his original premise to consider how performance might model and activate the social body.

To understand how this might be articulated, Lotte van den Berg and Daan ‘T Sas’ “dialogic artwork,” Building Conversation was performed on three occasions during Performatik, using three different models of which I participated in The Agnostic Conversation. The location at Varkensmarkt was only temporary, serving as a neutral meeting point for the “audience.” Given ten minutes to informally conversate over drinks we then migrated across Sainctelette to a vacant room at the Kaaitheater. There, both artist and audience entered into a choreographic exercise in un-scripted dialogue. The single prescription from the artist was to engage in conflict within the framework of philosopher Chantal Mouffe’s “agonistic pluralism” and Maori traditional practices in conflict resolution, which both offer structures for opposition within a shared symbiotic space. Agonistic pluralism advocates for a social plurality where adversarial differences are respectfully maintained. In similar ways, Maori ritual similarly preserve opposing views yet mediate their division through reflective listening during a process that begins with speaking across each other to speaking together while laying on the ground, temporarily suspending hierarchy and division. In Building Conversation, the group split into two opposing camps. But as with agonism the point was not to reach consensus, which Mouffe argues only serves to solidify our social and political divisions. Rather we were going to experiment with ongoing dissensus, where continual dialogue and disagreement is possible among adversaries. Interestingly, Mouffe’s abstract logic of socio-political conflict materialized in the Maori shifting arrangement of our bodies within the space, from initial physical and verbal polarization to a non-hierarchical discursivity. The process of moving from defensive hostility to dialogical openness through conversation and physical posturing brought a new awareness to the possibility of constructive dialogue across difference. After three hours we left Kaaitheater, making the same journey back to our original location and informal discussion over food and drinks. No doubt the participants left the dialogue different from when we had entered it, but ultimately what transformed? Performatik’s Salon series, panels composed of artists and speakers discussing various topics related to the program, was the second salon dedicated to the topic of Social Sculpting. During the conversation, Lotte van den Berg, one of the participating artists on the panel, explains that the performative dialogue was partly intended to rehearse different modalities of conversation. In doing so, one can look critically at traditional patterns of address and how they shape our social relationships, while also potentially transforming them. In the context of a Performance art Biennial, the artistic framework tended to impinge on the transformative power of the conversation as the participants occupied a liminal space between reality and fiction. That is, on the one hand we were participating in a debate about real issues stemming from our own personal and political perspectives, and therefore invested in some respesct. On the other hand, we knew this conflict would soon end, and therefore the conversation took the form of a rehearsal and an experiment in affect.

The performative dialogue initiated by van den Berg, however, did form a collective experience and social bond, albeit provisional, that became more apparent during the course of the Biennial as I re-encountered other participants, precipitating further exchange and reflection. This outcome can be compared to other works in Performatik which address the social in a more orthodox form of representation, such as Trajal Harrell’s Caen Amour. Much like traditional performance, this work offers a moment of communal experience and similarly requires the viewer to negotiate the production through new codes and conventions, but the dichotomous opposition between work and viewer remains in tact,

Harrell’s attempts to dissolve this binary by inviting the audience to traverse the physical barrier to view the inner workings of the hoochie coochie show behind the stage was intended to involve the audience as “co-creators of the show.” The production of this work however is not actually at the interstices between artist, performer and audience member. Knowledge was still imparted on the audience, whereas in Lotte van den Berg’s co-production knowledge is collectively formed and mutually dependent vis-à-vis discursive exchange. Additionally, in leaving the pure, neutral spaces of the theater or museum, the use of a different spatial context eclipses the distance and formality between art and viewer, similar to the terms of Allan Kaprow’s blurred line between art and life. For Kaprow, sustaining the fluidity between these categories was about maintaining the unpredictable, generative effects of the outcome, which are generally foreclosed in a traditional production or work.

Ant Hampton’s eloquent work Someone Else is an experience that hinges on the sense of social isolation as well as a proposition for breaking down those walls of separation. Characteristic of Hampton’s autoteatro, the performance invites the visitor to enact the work through a series of task-based instructions. Inside Beursschouwburg’s foyer facing Auguste Ortsstraat, you and another participant are virtually encased in the theater as you look out to Brussels’ bustling center beyond the windows. Wearing headphones hooked up to an ipod you listen to two voices that speak for you and your partner, uncannily expressing your thoughts and feelings. The artist punctuates the conversation with his directions that entail engaging with the space and your partner in silent movement and gesture. Oscillating between artifice and reality, the energetic life outside the theater’s walls become more acute. At this moment, a shift takes place in the performance in which Ant’s instruction turns to a proposal, asking you to initiate a conversation with someone beyond the normal parameters of your social sphere. The following direction to step outside the theater and wander, positions you as flâneur of sorts as you experience the city through movement and observation, carefully immersing you in the downtown social fabric while maintaining a critical distance to it.

In the range of what social sculpting can be Someone else is again playing with the liminal space between real and artifice, which is explicit as one moves in and outside of the theater. More importantly Hampton’s work is a provocation in dismantling your social alienation or a first step in producing a new sociability. To evoke Nicolas Bourriaud, the artwork’s script becomes a space of encounter of non-scripted social interaction.

The critique of social practice, largely wielded by Claire Bishop, is that the “intersubjective relations” these social works propose to generate is an insufficient end in itself. For Bishop, the problem is how do we measure the aesthetic value? In the case of Hampton’s work, is it enough that we followed through on his proposal of initiating a conversation with someone outside our social bubble? Or is Lotte van den Berg’s staging of a contested discussion a viable attempt at social amelioration, and if so, what constitutes its aesthetic content? What is perhaps more compelling to Bishop is what sort of relation is produced or what sort of critical awareness is generated from these relational encounters.

One quality in Performatik’s performances working under the rubric of “social sculpture” is the tendency to reify the sort of feel-good aesthetics often found in socially orientated artworks, which seek to sculpt artificial micro-utopias or micro-communities. However I would argue that the works under discussion do not obscure the possibility for tensions and friction to emerge from sculpting the social. There is a deliberate element of openness and unpredictability that allows for a nuanced sociability to form. In Lotte van den Berg’s work, in line with Mouffe’s agnostic pluralism, disagreement and difference is the productive element of the social engagement.

Considering Meg Stuart’s collaboration with Jeroen Peeters and Jozef Wouters, Atelier III is an on-going site-specific performance that negotiates the context of their space – an old factory building in Molenbeek that has been transformed into Wouter’s studio - and the implications this has on the development of their work. Wouters, a sceneographer, moved in last 2016 and will occupy the factory for a couple of years, working on various projects with different artists, as a resident in artist within Stuart’s dance company Damaged Goods. Atelier III is their first development and is more a verb than noun, with its emphasis on the working process and how the site’s multiplicitous dimension might formally direct it.

Apart from the material structure, Wouters refers to the “social eco-system” that informs this particular work. Like their artistic counterparts, Stuart, Peeters and Wouters insist on a collaborative effort, taking account of the variable expressions of collectivity across the performers, its audience and Molenbeek’s residents that create the larger work While the social here is modeled again through social engagement, one which is interestingly prolonged in comparison to Hampton’s one hour or van den Berg’s three hour exchange, the encounter that coalesced over the course of three nights during the biennial does not begin to reckon with the social complexities and power relations that the Atelier inserts itself in, potentially disrupts and reshapes. Furthermore, the long duration of the work, over years and across projects, is designed to counter the single-event in favor of building conversation and social relationships over time. While the artists do not claim to know what will result, they certainly pose a new model for an exchange that might endure or become meaningful, particularly for the community in which the artist is making their intervention. Bishop’s probing questions are quite relevant here, particularly if we ask what sort of relationship is actually generated from these relational encounters in Atelier III? Is the meaning a product of the exchange between performers and production team, performance and audience, or artists and community? Where do we locate the social here? While the artists acknowledged the understanding that there is always already a social context in place in which the artist is working with, the Atelier is a form of social practice and performance that finds itself in the midst of the enduring negotiation between the aesthetic and ethical dimension of social sculpting. Thus far, social practice has yet to transcend this dilemma, but which artists remain committed to. In the context of performance and Performatik more specifically, social sculpting appears to asking what new form a critical art of the social can take.