an epic that opens up into a dream

over Retour Amont: le Rêve

text Julie De Meester.

Before Retour Amont: le Rêve, there was Retour Amont, a duet created by Claire Croizé and Etienne Guilloteau in the fall of 2020, which brought the two choreographers back on stage for the first time in more than five years. Guilloteau and Croizé have been partners, artistically and in personal life, for much longer than that. This piece was a return to their origins, reaching into the physical memory to retrieve material from previous creations in which they danced together. At the same time Retour Amont was a reflection on the present, a reaction to the period of isolation and uncertainty that we experienced in 2020. For the live music, a staple of ECCE’s oeuvre, they reconnected with Guilloteau’s old companion de route, the musician and composer Alain Franco, as well as teaming up with Jean-Luc Plouvier of ICTUS.

In 2021 this team was joined by the violinist Aisha Orazbayeva and the dancers Claire Godsmark, Emmi Väisänen and Gorka Gurrutxaga to make a new creation, Retour Amont: le Rêve. Guilloteau took ideas for an unrealized creation and combined them with the choreography of Retour Amont to create a new piece that carries his signature, but that also blurs traditional notions of authorship. Similar to sampling a piece of music, the material of Retour Amont is there, clearly distinguishable, both a reference and a part of a new and irrevocable whole. According to Guilloteau this is just one of many layers in the piece, happening at the same time but seeming disconnected. Watching these different realities shift across and alongside each other is both disorienting and enchanting, like stepping into someone else’s dream.

When they created Retour Amont, Croizé and Guilloteau wanted to rediscover the body as a site of possibility and connection, in defiance of an increasing sense of alienation brought on by the lockdown. In Retour Amont: le Rêve, that material is combined with Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1), more specifically the tale of Io, the nymph who was transformed into a cow and pursued across the earth. Changed to a strange form, cut off from her loved ones and held captive, Io too is robbed of her voice and of agency over her body.

As with many of ECCE’s pieces (EVOL, Flowers (we are),…) texts are expressed through the body, but the approach varies greatly depending on who is speaking. Claire and Etienne both “say”, word for word, fragments from the work of French poet René Char, such as:

Dans le ciel des hommes le pain des étoiles me sembla ténébreux et durci, mais dans leurs mains étroites je lus la joute de ces étoiles en invitant d’autres : émigrantes du pont encore rêveuses; j’en recueillis la sueur dorée, et par moi la terre cessa de mourir. (2)

Poetry might be the best medium for this, as the experience of reading it is not very different from watching it translated into movement: even without fully understanding it, you can absorb the emotion – and sense the voice of the speaker.

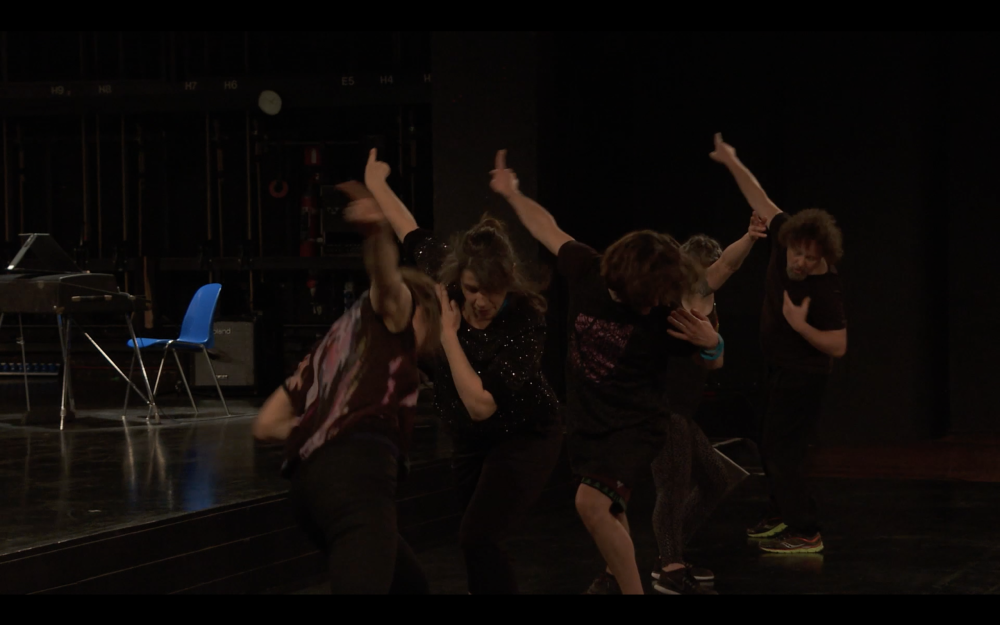

The other three dancers have a looser relation to their source material – the story of Io – which translates to a less gestural, more organic movement language consisting of textures and inflections rather than syntax. Nature, strongly present in Ovid’s text and a recurring motif in ECCE’s repertoire, makes up much of their inspiration, yet the mountains, brooks and trees that they express with their bodies are felt rather than seen. Traveling the space, it is as if they are mapping out a landscape, rich with possible narratives. One moment they float lightly across the stage, then suddenly they move with force and ardour, tossing their heads and hands to the sky as if in supplication. At times they seem almost like the chorus to Guilloteau and Croizé’s protagonists, annotating their movements by copying them – and then a sudden role reversal or scene change complicates such easy conclusions.

Equally dramatic is the penetrating sound score of Franco, Plouvier and Orazbayeva, that drives the movement in Retour Amont: le Rêve. Together with the rest of the team they selected compositions from the greats of contemporary classical music – Cage, Sciarrino, Ligeti, Nancarrow, Schoenberg – which are performed on two opposing grand pianos, a Fender Rhodes, and a violin. The musicians too stay in motion, traveling the scene between various stations. Guilloteau worked closely with them, tweaking movement, dramaturgy and light to achieve a delicate balance. Take for instance Guilloteau and Croizé’s playful duet, where they skip around each other like boisterous schoolchildren, accompanied by the acrobatic twists and turns of Nancarrow’s Study 6 for two pianos. And yet, the possibility of a harmonious picture is just as often disrupted. One such disruption is the repetition, seemingly at random, of a low droning sound throughout the piece. While grounding and tightening it, drawing us back to the present, this sound also adds to the dreamlike atmosphere of Retour Amont: le Rêve. Or rather, it reminds us how easily that dream can take a nightmarish turn.

Jean-Luc Plouvier not only plays, but also uses his voice, adding another layer to the choreography. He recites part of a lecture by the French philosopher Michel Foucault; Le corps utopique (3) (1966), which add richness and context as well as, perhaps most importantly, musicality. In this text, Foucault describes the body as a prison in which we are trapped, but also a portal through which we connect with the world. Plouvier’s rendition of the texts is really a re-enactment of Foucault’s lectures. As such his voice become another part of the piece’s musical score, an experience of texture and cadence. To drive this point home, the dancers dance and embody words from the text as it is spoken.

These migrations across the register of music, movement and space tie into a central theme of Retour Amont: le Rêve: that of wandering and crossing borders. As Io crossed the Bosporus, so this piece wanders the space of the theatre and transgresses the boundaries between audience and stage. Building on years of research, Etienne Guilloteau takes this exploration to a radical level in Retour Amont: le Rêve. On May 24th in the Kaaitheater all the seats were removed, so that the normally rigid divisions were not just blurred, but almost effaced, and the perspective was scattered across the space. Guilloteau describes metamorphosis as “a transformation so great that it transcends what you can expect from the original form.” In this case, the radical redistribution of space gives Retour Amont: le Rêve the allure of an epic, and opens it up into a dream that many can share: a return to old connections through new and untrodden paths.

1. The Metamorphoses, Ovid, book I, 568-587-Inachus Morns for Io

2. Lutteurs René Char, in the collection Le Nu perdu, ed. Gallimard 1971

3. Michel Foucault “Le corps utopique” a radio broadcast conference from 1966, Michel Foucault expose an ambivalence of the body with its relations with space. It is here and everywhere at the same time. He describes the body of the dancer as “…dilated along an entire space that is both exterior and interior to it.”