What if an avatar refuses the commands of the players?

A conversation with Thiago Antunes

A conversation with Thiago Antunes, by Eva Decaesstecker (Kaaitheater, February 2021)

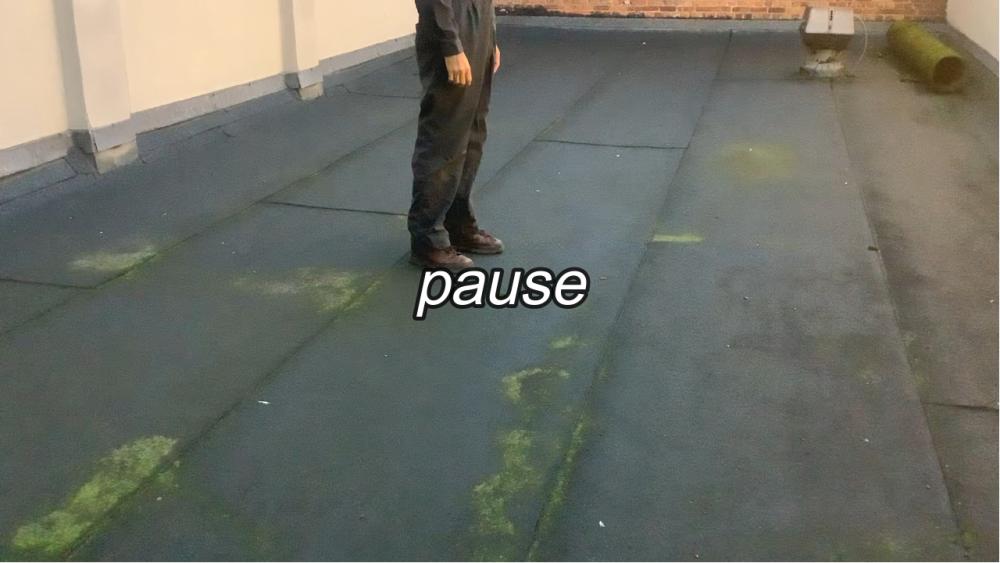

Thiago Antunes used his How to Live and Work Now-residency to develop an escape game, called Job. In this game, participants (who play the game via Zoom) have to guide an avatar out of the labyrinth of the theatre building. But the avatar, called Macmann, does not always feel like obeying orders…

A conversation on civic integration through work, the power of collaboration and on how having a multitude of jobs can become a performative act in itself.

During your residency at Kaaitheater, you have been creating a game, but this is not your first game. How did you start creating games as performing arts?

When I came from Brazil to Belgium, I had to deal with a lot of bureaucracy, as most migrants have to. I soon realised that I had to organise my life in a strategic way in order to get what I wanted. I wanted to move to the Netherlands, but I was not accepted. I’d have to go back to Brazil, learn Dutch there, pass the ‘inburgeringsexamens’, the civic integration exams, before setting foot in the Netherlands. But I stayed in Belgium and a few months later, I got admitted to the post-graduation in performance studies at a.pass.

I became fascinated about the ‘inburgeringexamens', and the notion of becoming a citizen by undergoing multiple choice exams. Therefore, I started creating works that would mimic and elaborate on these educational process of learning how to adapt to Europe. I discovered games were nice platforms for me to deal with my own bureaucratic issues in a more playful manner. Back then, I also learned about this genre of game called escape room, in which the players are locked in a room and have to find hints and solve puzzles in order to escape. As a migrant, I could totally relate to that situation of seeing reality as a puzzle to be solved within a certain amount of time. I found myself busy learning languages, obtaining documents, trying to make a living and also trying to find some sense of belonging. At one point, I got a job as a game master in an escape room, which helped me to understand how the escape games were made and how the sessions could be handled. I started to create a few games myself, inspired by the civic integration exams, which took place in fictional countries where the players have to learn languages, get a job, or get intimate with a stranger. Just as in the actual exams, where work is considered as a main part of the integration process, my games revolve a lot around work and work relationships.

The job aspect is indeed a recurrent topic in your work. The game you created at Kaaitheater is even called Job. Why is this so important to you?

My experiences working as a migrant were important to understand the Belgian and Dutch societies. Work reveals the cross-section between the private and the public spheres very well. It allows you to do certain things, to circulate in certain spaces, to use certain words and clothes. It is a performative action that transforms your own identity through the repetition of gestures. In Inburgering in W., the game I made for the ENTER festival, the players come across a performer who plays a native citizen speaking a fictional language. One of the main puzzles they have to solve is to convince him to give them a job. They need coins to pay for the exam at the end of the game, so it is not an option not to work. They end up cleaning up the rooms of the game and serving him food. That is also the only way for them to learn a little bit of the native language, only enough to pass the exams without fully understanding them.

It is not a conventional escape room: the players have to cheat in order to evolve in the game. For example, at some point they have to learn how to cover the security cameras in order to do things they are not allowed to. Thus, there are many levels of rules at play. Part of the game is to decipher what the actual rules are.

How did you come up with the idea to create a virtual avatar? Is it a result of the corona situation, not being able to bring people physically together? Or had you already thought about creating a digital game?

The idea of an online game came because of corona. I started having so many Zoom meetings, from work meetings to parties, and I realised that I was more than ever performing before the camera, becoming an avatar of myself, taking care of the scenography appearing behind me. I became curious about this ‘avatarisation’ of ourselves.

In the other games I created, I am not performing myself. I am present as the game master, watching through a camera and giving hints to the players. I am the audience of the audience. This time, it is the other way around: I am the avatar guided by the participants who can see me on Zoom. I obey their commands, or not.

What place does the work aspect gets in your new game Job? In contrast to your previous games, when playing this one, you do not feel like working.

Maybe the players do not want to work, but the avatar is working all the time. The relationship between avatar and players is similar to the one of an employer/employee. There is a constant exchange of power between these poles. Who is actually in command? I started from the questions: what is work? When am I working? What are the inner voices that push me to work? As an artist, we consistently feel the obligation to produce, to show improvements, to gain more visibility. As a non-established artist, I still struggle with survival. The Thiago who writes applications might sound like somebody who is constantly busy with his artistic practice, but I only dedicate myself to my artistic practice when I have time and money. I have started to see having an artistic practice as a privilege that many cannot afford.

Because it implies an ongoing-ness?

Most artists I know live in a state of precariousness. Job is an attempt to elaborate on the different roles I play in life, combining my experiences as a migrant worker and as an artist to see how the one mirrors the other.

In fact, my work experiences are my most performative practice: to change the cap and to pretend – I am a waiter, then a gardener, then a Deliveroo guy, then an artist in a residency, then I am a dancer, then I give massages, then I translate, then I write applications. I play with the invisibility that comes along with the position of a worker, and then reshape those experiences into something playful.

Job is a way for me to imagine what happens when I refuse to follow what is expected, as an artist and worker. It is an investigation into where my desire takes me when I stop listening to external demands.

Can we say art is the place where you can bring these different identities together?

I think so. Otherwise, I do not think I could handle it. Art is a way to elaborate on these experiences that are not always pleasant. I am working to feed my artistic practice, even when I am working to get money. It is a way to re-signify things.

Coming back to Job, is the character of the avatar based on a specific figure?

Yes, it is inspired on two characters from two different novels. Macmann is a character from the novel Malone Dies by Samuel Beckett. Every time Macmann works on something, it goes wrong. The harder he tries, the worse things become: for example, when he sweeps a place, it looks dirtier after he cleaned it. My idea was to create a bad avatar, an avatar that is not efficient even though he is trying his best. Many times, as a worker, I realised that the more engaged I was, the more clumsy I was too.

The other inspiration is Bartleby, the character from Herman Melvin’s Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street. He is a scrivener – he copies texts – who suddenly refuses to revise his work, saying “I would prefer not to”. At some point he starts refusing everything that is asked from him. Finally, he stays in the office and the company decides to move out because Bartleby is now living there, not doing anything, refusing every request. What if an avatar refuses the commands of the players?

What will you take with you from this residency? There is the game you made of course, but are there other things as well?

Totally. I applied for this residency with the idea to create a game on my own. I managed to create a routine of writing every day and making some puzzles. But the actual process started when I invited other people to come. First, Gaëtan Rusquet assisted as an external eye. Then Damien Petitot helped me technically with the videos and cameras. After two weeks of residency, I realised that I really should start with working with people. I can come up with a few things, but I need players to interact with me, to see if it works. So the next time I will definitely involve others from the start.

For a game like this, the technical part should be done first. I left it to the third week, but the whole dramaturgy changes depending on which cameras you use, which operating system etc.

Is this game only made for theatre buildings or do you have other places in mind as well?

I very much liked the atmosphere of work spaces, like storage and technical rooms – they also appear in my other games. Places that are not very clean, with machines you do not recognise, with stuff being stored without you really knowing why it is there. I also like technical work outfits. I wanted Macmann to really look like a worker in a more worker-like surrounding. I do not see myself doing this in an office or some fancy house.