Kaaitheater 1977 - 2017

a history

1977-1985 THE KAAITHEATER FESTIVALS AND VZW SCHAAMTE

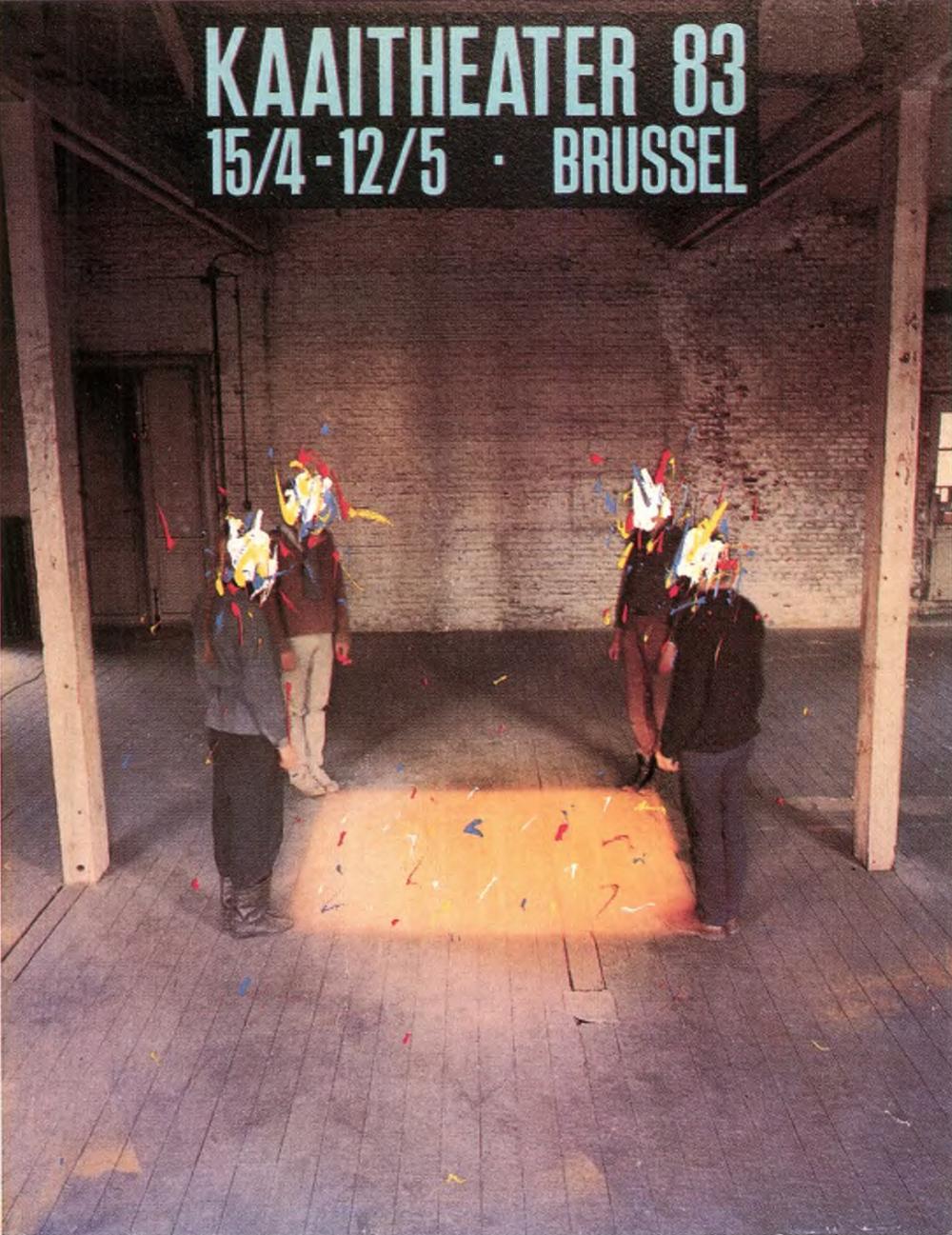

The history of the Kaaitheater began in 1977 with the organization of the first Kaaitheater Festival. Five festivals were organized between ’77 and ’85. The examples that Hugo De Greef, the programme director of that first festival had in mind were the festivals of Nancy, Avignon and Edinburgh, the Berliner Theatertreffen and the Holland Festival. The programme that he assembled was a necessary supplement of artistic contributions from Belgium. A temporary function was attributed to the festival: as long as people abroad do it better than here, or: ‘until here in this country an equally invigorating, progressive theatre movement reaches its stride’. The most powerful and most coherent edition, however, was doubtless that of 1983. ‘The prospect of a new theatre climate in Flanders’ that was held out in 1977, had indeed been realised with tremendous speed: Jan Decorte, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Jan Fabre, and Jan Lauwers easily took their place at this festival alongside Gerardjan Rijnders, Jürgen Gosch, The Wooster Group, Steve Paxton... The festivals had enormous impact. The feeling of being present at the birth of a new language, the feeling of witnessing a new élan, of being a part of it: this was what audiences thought.

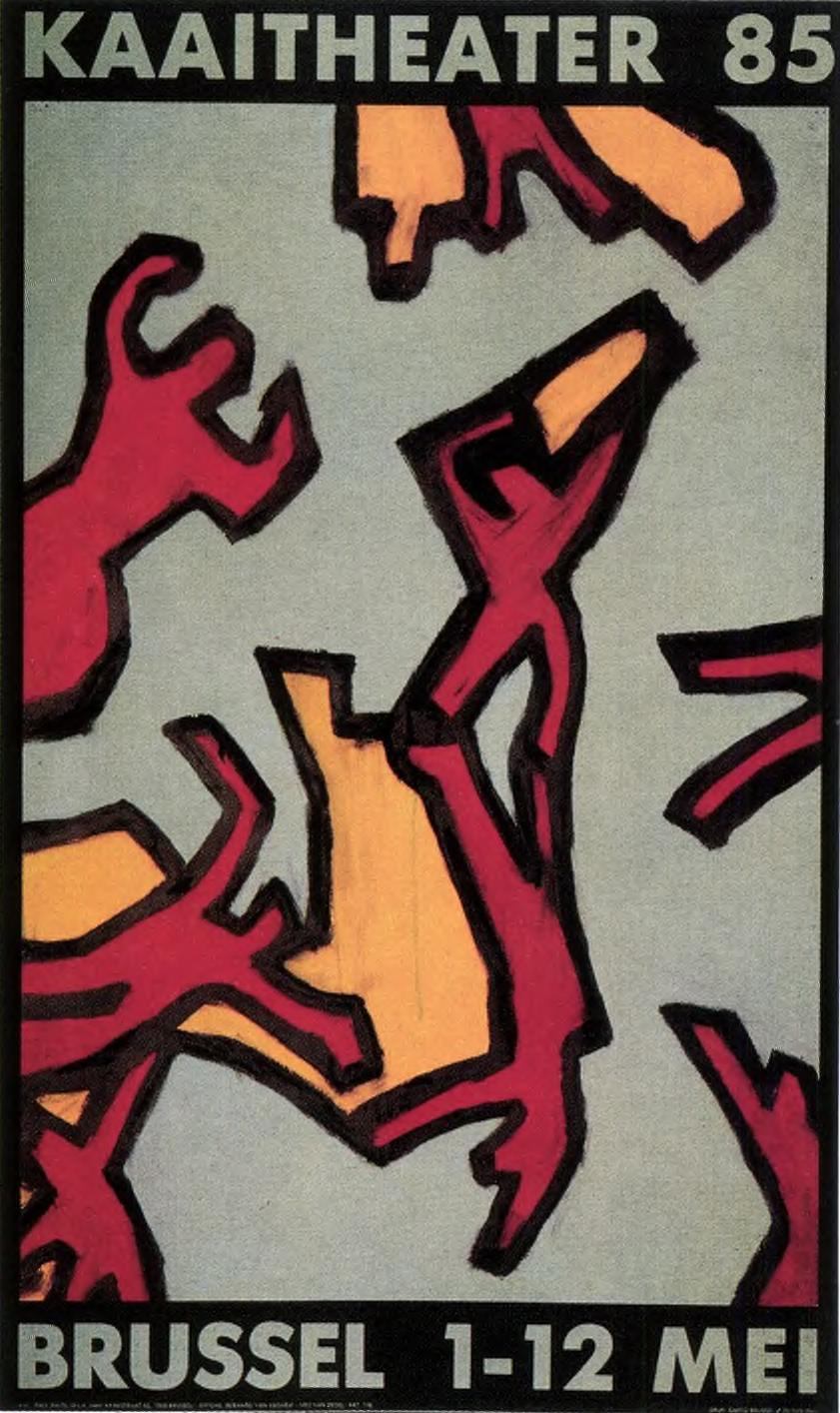

The conclusion drawn after the last festival in 1985 was that the Kaaitheater needed to suspend its festival formula in favour of regular yearlong operations and for produced work to increase in importance at the expense of the receptive. A number of these Flemish artists/groups had in the meantime already developed Schaamte within the artists' association, of which Hugo De Greef was also the impassioned organizer: they were the basis that could support the yearlong programme. The production activity that was limited in the festivals – for financial reasons – would receive primary emphasis in the annual programme. The logical consequence was that the Kaaitheater and Schaamte would merge. In 1983, the Kaaitheater acquired its own home for the first time. The old Etoile brewery and adjacent brewer’s house were first occupied (and currently house the Kaaistudios).

1987-1993 ARTISTS' CENTRE KAAITHEATER IN ITS NOMADIC PERIOD

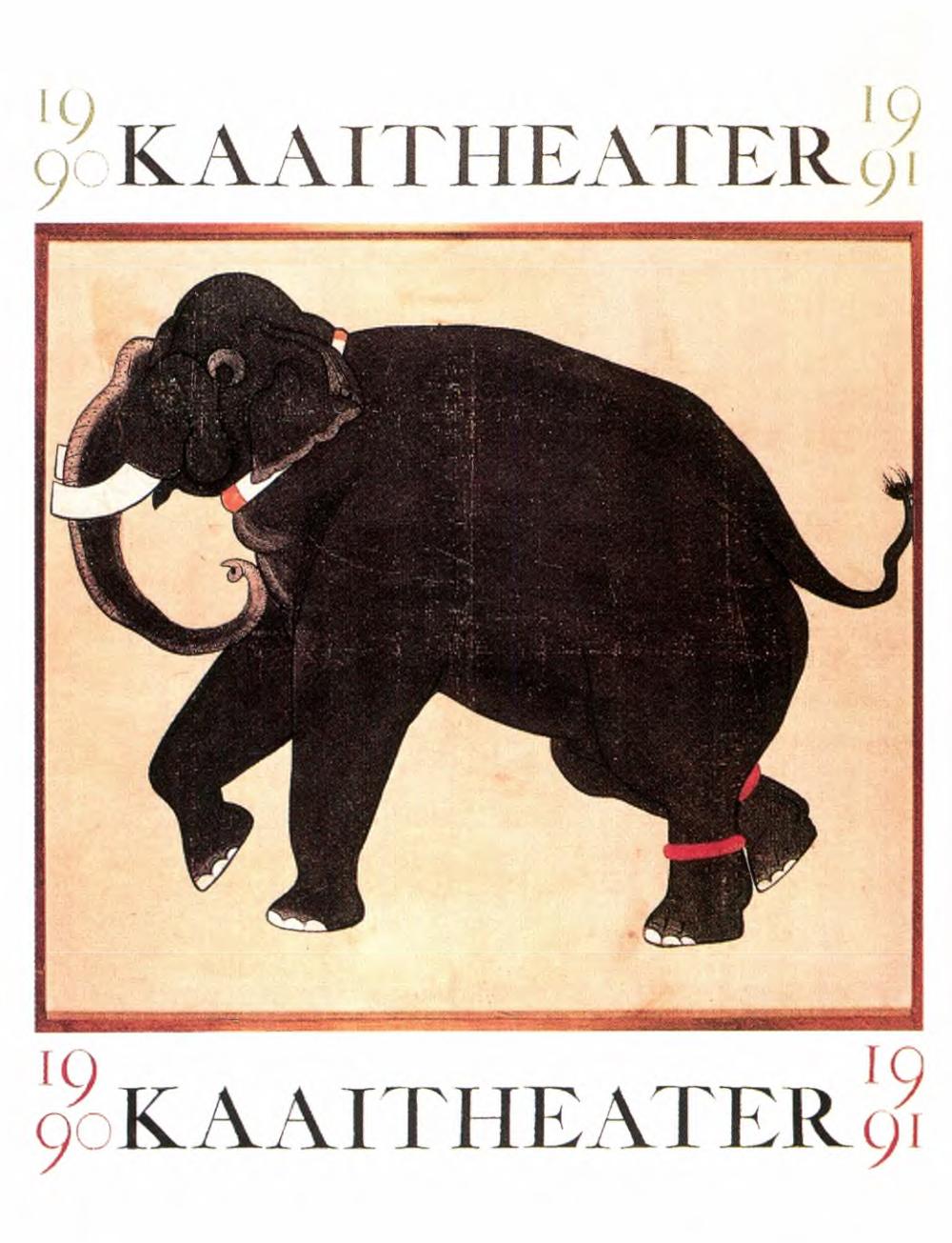

While the motives for it were transparent and organic, the transition from festival-based to seasonal operation and the fusion of Kaaitheater and Schaamte were not self-evident. The first season started on 1 October 1987. On 1 January of that year, the group Rosas became legally independent. The merger between Kaaitheater and Schaamte officially started on 1 January 1988. The objectives of the new non-profit organization with the name Kaaitheater were threefold: produce, present and distribute that which was produced. In its nomadic period, the Kaaitheater organized productions at La Monnaie, the Ancienne Belgique, the CBA (the present-day CVA in Anderlecht), the Halles at Schaerbeek, the Théâtre de Banlieu, the Théâtre National, the Théâtre 140, the KVS, the Palais des Beaux-Arts, the Beursschouwburg. In other words, a lot of money and energy always had to be invested just to show its own productions in Brussels. This yielded contacts and forms of collaboration with many colleagues in Brussels, in Dutch as well as French. But how can one expect to establish a permanent presence as a Brussels theatre without theatre infrastructure and without the power that is particular to a festival? Wandering from theatre to theatre made the Kaaitheater a travelling company in its own city. The search for our own theatre began.

The entire operation to turn the Kaaitheater festivals and Schaamte into a new Kaaitheater, the choice to follow artists and allow them to be followed by their audience was nevertheless unavoidably associated with a feeling of loyalty, a search for depth in relationships (with the artists, with an audience, with society). A feeling that was then already accompanied by the awareness that promoting the interests of continuity was not self-evident in the ‘consumer society’ that surrounded us. Thus it was a choice that entailed risks. An awareness that vulnerability, nuance, the search for depth and interiority were not values that were self-evident in the market.

1992-93 was the last season of the Kaaitheater's nomadic existence. In June of 1993, we moved with our offices to the Lunatheater, which we would share with the Ancienne Belgique for the following three seasons: the beginning of the sedentary life, of the certainty and the strength of our own theatre infrastructure with which a real relationship could be entered into with the City of Brussels and its theatre history.

1993-1998 COMING HOME?

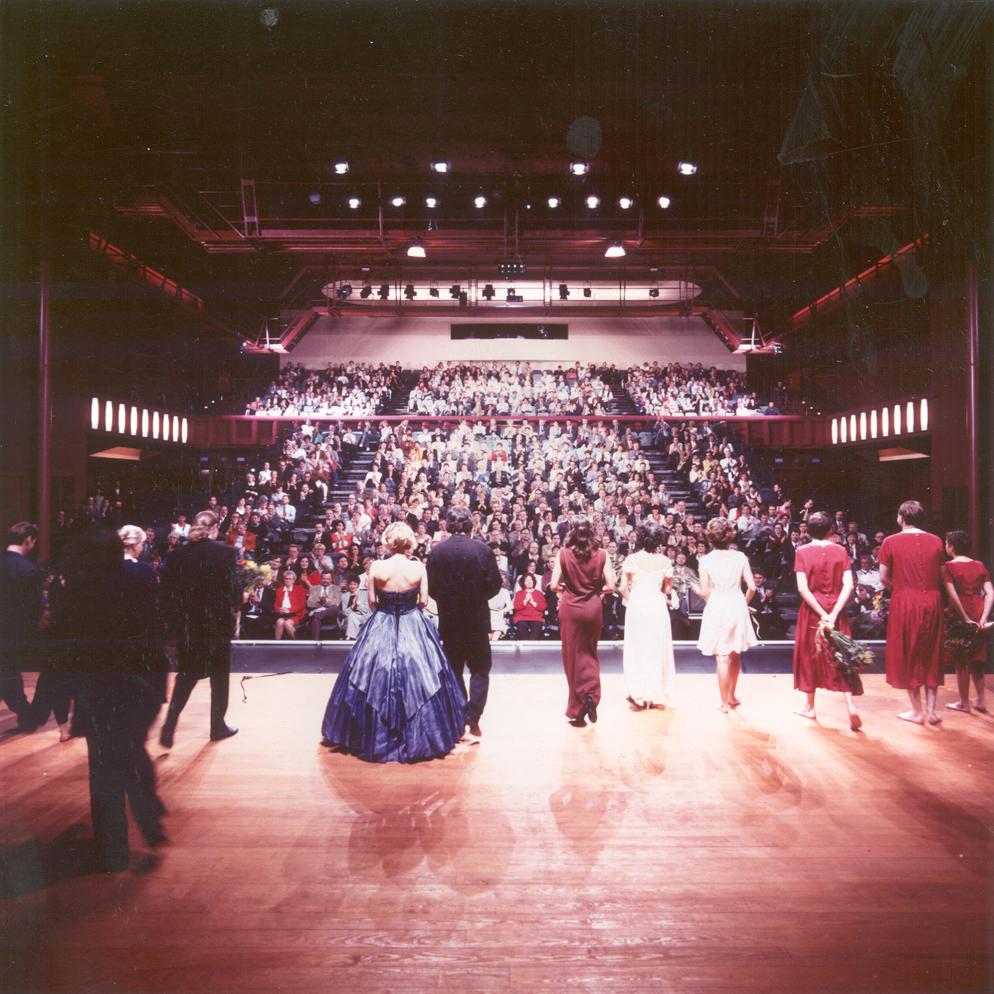

The move to the large Lunatheater raised many questions. What then does it mean to mature artistically? Is having a permanent place of residence indispensable? Does growing old in the world of art also de facto imply becoming larger? Is it possible for a newly created theatre language to gain acceptance with a wider audience? These and many other questions occupied us, captivated us in a certain sense, when in 1993 we moved to the Lunatheater and began to present productions there, commencing with the 1993-1994 season. Moving into that large house was one thing, but perhaps even more drastic was the fact that this coincided with the closure of the small house: the last production took place in the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Vaakstraat Studios in April 1993; then the doors closed for more than one year for renovation work. This double move turned us into displaced persons: nothing was what it used to be and nothing was what it could be. We were in no-man’s land, between the old that we wanted to consolidate and the new that was to come. There was fear getting caught up in the treadmill of institutionalization and bureaucratization, and we realized that we were no longer only occupied with serving artists but also with maintaining ourselves as art centre: ‘Initially intended as protection of what is dear to you, the house itself quickly becomes the most important thing to be protected.’

Beginning with the 1996-1997 season, a two-track programme was developed: Hugo De Greef selected the projects for the big stage, on which mainly the permanent Kaaitheater artists found their place, and assistant dramatist Agna Smisdom realized a ‘different coloured’ programme of mainly young artists in the Kaaitheaterstudio’s. This decision shows that the Kaaitheater, albeit with much hesitation, began its transformation from artists' centre to arts centre. The acquisition of the twofold infrastructure of the Lunatheater and the Kaaitheaterstudios de facto meant increased pressure to have ‘these houses perform’ and therefore to give priority to the receptive over the producing work. This emerged from a changed responsibility with respect to the audience and the government, and also presupposed a totally different way of dealing with the artists than that which we previously employed. And that was probably the biggest revolution in our work. Indeed, it presupposed ‘being unfaithful’ to people, ideas, and methods that for years had belonged to the essence of the work.

In this problematic context, the decision of the government to allocate only 45 of the requested 66 million Belgian Franks subsidy for the four-year period 1997-2001 came as a shock: Hugo De Greef considered this decision to be a rejection of his work and it became the immediate occasion for his departure. In the new financial situation, producing performances in-house, in the way we previously had, was basically impossible. It felt as if the Kaaitheater was being required to personally amputate its own ‘heart’.

1998-2020 CONTINUITY AND INNOVATION

After the departure of Hugo De Greef, there were three available options concerning the future: 1) find a new director for the entire operation, 2) work out separate solutions for the Lunatheater and the Kaaitheater Studios 3) close the entire operation. The Kaaitheater board of directors was unambiguously in favour of the first option. In 1998, Johan Reyniers became artistic director and Hugo Vanden Driessche became general manager.

Johan Reyniers opted on the one hand to ensure the continuity of the Kaaitheater project and on the other hand, to implement the changes needed for running an art centre with two infrastructures in this ‘new era’. The most important change in this area was without a doubt the enlargement of the artistic possibilities available with which to work. With his arrival, the old Kaaitheater generation also assumed major roles (including financially) within the programme. In addition to continuity, more space for innovation had to be created. Johan Reyniers was aware that the Kaaitheater – with its two infrastructures – needed many artists belonging to different generations for productions intended for large as well as small audiences, using resources that could be a part of diverse disciplines. It was a difficult balancing act between the 80s generation, that of the 90s and later that of 2000. At the moment of his arrival at the Kaaitheater, the artistic centre of the theatre was occupied with the phenomenon of the ‘collectives’ that had developed from or within the tradition of Maatschappij Discordia (and then especially Tg STAN). Thus for him it was only logical to bring in the grandchildren of Maatschappij Discordia such as Dood Paard and ’t Barre Land. Perhaps most associating himself in that period with the work of ‘the nineties’, by artists and groups such as Meg Stuart and tg STAN, he presented the work of artists whose ‘starting point’ had been the Kaaitheater – such as Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Josse De Pauw, Jan Lauwers, Jan Ritsema – and introduced new names to the programme such as Jérôme Bel and Raimund Hoghe. In the first decade of the 21st century, a new élan could be felt in the ‘discipline’ of performance, which alongside theatre, dance, musical theatre and music, became a permanent feature of the programme: this younger generation of performance artists, which include people like Kate McIntosh and Kris Verdonck, were given their place in the Kaaitheater programme. The ten years of Kaaitheater under the artistic direction of Johan Reyniers, the period 1998-2007, are discussed in detail in the text by Pieter T’Jonck. Johan Reyniers and Agna Smisdom were responsible for the programming in the 1998-1999, 1999-2000 and 2000-2001 seasons; after the departure of Agna, Johan alone would handle the programming for three seasons. Since the 2004-2005 season, Johan makes the selections along with Petra Roggel, but he retains the final responsibility with respect to artistic matters. The arrival of Petra Roggel can be associated with the renascence of performance as genre: an area – together with that of ‘new dance’ – that Petra knows very well.

2008 – THE PRESENT: OPENNESS, SOCIAL CONTEXTUALIZATION AND COLLABORATION

In 2006, Johan Reyniers announced his departure. He would organize his tenth season, but stop afterwards. In May 2007, Guy Gypens and Katleen Van Langendonck were appointed the new artistic directors. 2008-2009 was their first season.

The Kaaitheater had always considered the artist to be ‘a researcher of the world’, an important social inquirer. That world had only been getting wider after 1989, and the questions that had to be asked were increasingly complex. In this respect, 2007 was not a reassuring year. The credit crisis struck and painfully demonstrated the powerlessness of politics within the global economic system. The IPCC published its fourth report on climate change and for the first time, it stopped hiding behind scientific neutrality. The situation was very serious. It gradually became clear that the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall would not be a tremendous celebration. Philosopher Peter Sloterdijk wrote about twenty years of irresponsible frivolity. The call for the re-politicization of society became louder and louder.

The new artistic directors of the Kaaitheater wondered whether the role of the artist and art institution in this re-politicization didn’t urgently need to be rekindled. Could artists and art institutions remain in the margins any longer, asking socially relevant questions from a distance? This perspective of the new artistic directors did not mean that the autonomous position of the artist would be challenged or that there would be a radical break with the Kaaitheater’s artistic past. No, Gypens and Van Langendonck remained faithful to the great artistic principles and the majority of the Kaaitheater’s resident artists, but also felt a pressing need to open the place up even more in order to intensify its direct relationship with the outside world and to engage in closer collaborations with partners in the city. The position of service that the Kaaitheater had traditionally taken towards the artists and their autonomous work was to a large extent maintained, but it was supplemented with the autonomous position of the arts centre itself. The impression had been created that the Kaaitheater had spent the previous years concealed behind its artists and that the vehemence of the raging crises required the institution to position itself more directly. This ‘opening up’ was manifested along three main lines: in terms of content through the introduction of a thematic contextualization, spatially by literally working elsewhere (on location and in public spaces), and with respect to visitors by searching for new audiences through initiatives like Festival Kanal, Matinee Kadee and We have a dream. Intensive collaborations were established on these axes with partners in the city.

Gypens and Van Langendonck created a number of new ‘formats’ that each focused on a thematic perspective within a central core programme that clearly exemplified the artistic soul of the Kaaitheater. The Spoken World Festival was based on the theme of global interdependence, Burning Ice focused on the socio-ecological crisis and WoWmen was centred around gender issues. These formats did not aim to convey an unequivocal message, but were rather interested in the combination of artistically challenging work and incisive social debate. Each of these formats also involved collaborations with non-artistic partners in different social sectors.

Performatik was an exception to this thematic rule. The festival was a further development of what Reyniers and Roggel had tentatively started in 2006. It did not take long for Katleen Van Langendonck to turn Performatik into an important biennial for performance and live art. The relationship between performing arts and visual arts, between black box and white cube was central. It became a fully-fledged urban festival with partners such as Wiels, Argos, Bozar, De Centrale, Museumcultuur Strombeek Gent, QO2 and the Beursschouwburg. The method of collaboration was based on consultation between the various curators, both with respect to content and planning.

The renewed focus on international positioning and collaboration was also striking. In the early eighties, the Kaaitheater had been pioneering in this respect, but this role had faded after about the mid-nineties. Starting in 2008, the centre again became active in a number of important European networks such as Imagine 2020, House on Fire and – more recently - The Humane Body.

Marianne Van Kerkhoven died during the night between 3 and 4 September 2013. She personified the artistic history of the Kaaitheater like no other person. As a dramatist, she spent the last 35 years in the eye of our storm. The last thing she said to us was: “But the show will go on!”.

Epilogue on dramaturgy

"I remember. Je me souviens. In the end, however, the narration of history remains the construction of a story, a story that here, with respect to myself, comprises most of my professional life.

‘If we except those miraculous and isolated moments fate can bestow on a man, loving your work (unfortunately, the privilege of a few) represents the best, most concrete approximation of happiness on earth.’ (Primo Levi)

I think that I, in the Kaaitheater, due to this very context, have been able to learn to understand what dramaturgy is and how important it is, not only in art but also in life. I do not think there was any other place where this might have been possible. I am still unable to articulate what dramaturgy is. I am only able to intuitively ‘feel it’. I can immerse myself in it and know that ‘it is good’. It has to do with finding that point at which artistic freedom and freedom of thinking coincide. It has to do with finding that point at which the world and art, the theatre and society, coincide, where great and small dramaturgy can encounter each other.

With respect to small dramaturgy, today we do not need to be too worried. New artistic paths are continuing to emerge: the current élan of ‘performance’, the continuous developments in dance, multimedia theatre etc.

Large dramaturgy, however, gives cause for disquiet and anxiety: what path will this world follow and what place will art find in it? Is there still a place for the arts?

In my mind, artists are not heroes or geniuses. They are workers: they filter and clarify time. They translate and metamorphose time. They plough it and make it manageable. We need them. What they do is incredibly worthwhile. Because they – when things go well – are unbiasedly located in their experience, without alienation, without calculation. The conversation they have with the world must be able to seep through to the audience, who in turn will translate, metamorphose these words, sounds, movements again for themselves…

To take care of = to care for. Or vice versa.

Never knowing, continually seeking."

Marianne Van Kerkhoven