‘We share a physical sense of theatricality’

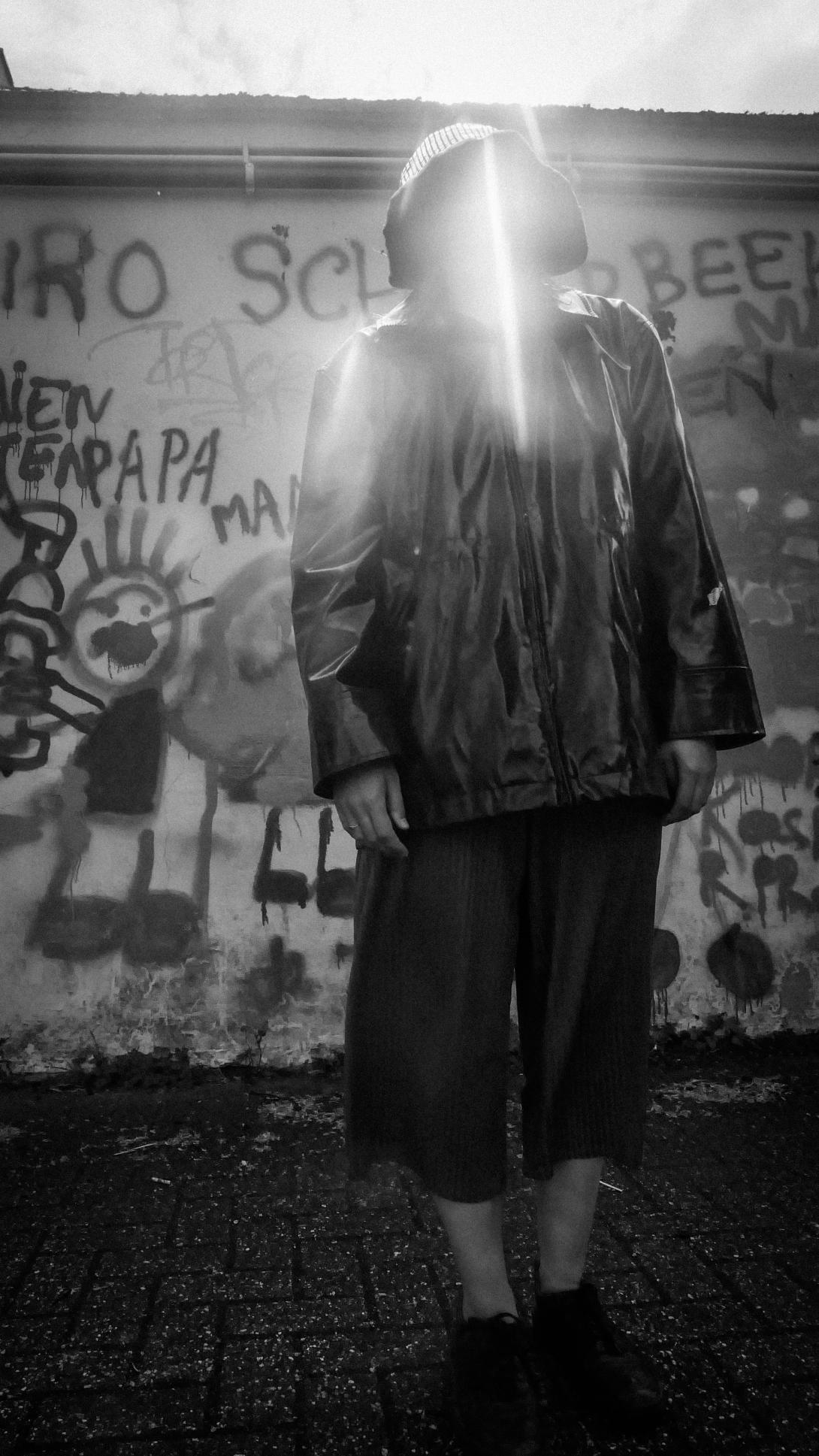

A conversation with Dareen Abbas & Rimah Jabr

Rimah Jabr currently lives in Toronto and works as a theatre maker. She is also in her first year as a PhD student in theatre and performance studies at York University. Dareen Abbas is currently a visual artist who lives and works in Brussels. Together they are creating Broken Shapes, which will première at the Kaaistudios in March.

Rimah Jabr started writing plays in a workshop in Palestine. The workshop led her to Belgium, where she studied theatre at RITCS. She currently lives in Toronto and works as a theatre maker. She is also in her first year as a PhD student in theatre and performance studies at York University.

Dareen Abbas graduated in printmaking before she finished her two-year Master’s at the Erg School of Graphic research. She is currently a visual artist who lives and works in Brussels. Together they are creating Broken Shapes, which will première at the Kaaistudios in March.

Where did you both meet? And how did you decide to work together?

RJ: When Dareen was looking for a place to stay in Belgium, a mutual friend put us in touch with each other. We became friends and started following each other’s work.

Three years ago, when I was already living in Toronto, I read about a residency programme at the Theatre Centre in Toronto. It was a two-year programme for artists, which would simply start from an idea. We decided to apply together.

DA: The idea from which we started was on the one hand very concrete, but we also wanted to see more generally what might happen if we worked together. We are interested in each other's work and we have good conversations about our artistic approaches. So why not try to put these things together and see what comes out of it?

I also noticed that we share a kind of physical sense of theatricality. I don’t make theatre myself, but I do have a strong experience of a kind of theatrical presence of matter in space. From this shared quality, we started to develop a character and a main focus on the spatial dimension.

You each have quite different practices: one works as a theatre maker, writing and directing, and the other combines different visual arts practices – video, sculpture, etc. Were you also curious to cross disciplines and switch roles? How do you work together in general?

RJ: The initial idea was to work with space and spatiality. This was then translated into a combination of Dareen’s world and the visuals and my texts.

DA: We are creating the piece together by showing each other what we are doing, but we stick to our own roles, though in a collaborative way. In the beginning, we really thought everything through together. Later, when the piece became more concrete, we separated the roles according to our backgrounds.

How did you both work together from a distance?

RJ: Due to the distance between us (Brussels & Toronto), we do most of the collaboration via Skype and on the phone. I think we would have made something else if we had been working together in the same room. On the other hand, this distance gave us the opportunity to put restraints on our active ability to make something, and that forced us to think the piece through conceptually. So in the end, it was not a bad thing, it just resulted in a specific way of working.

Broken Shapes tells the story of a young woman who discovers her father’s architectural drawings on the day of his funeral. Overcome with sadness, she slips into the imagined places that he created. How did you come up with this story?

RJ: I first developed monologues for a female character who was reflecting on her spatial cognition, because that was something I wanted to explore in the writing. But the character needed a framing device. I didn’t want her to be an architect because that didn’t make sense to me. We needed another line of approach for the architectural world. And then I came up with the idea of the deceased father who was an architect. The death of her father and the mourning period she goes through forms a context for her to discover architecture and explore space in relation to her mental state of grief.

What fascinates you so much about architecture and spatiality, Rimah? It comes back in Broken Shapes but also in you PhD research, so it seems to occupy an important place in your field of interest.

RJ: I can’t really point out what’s so fascinating about it. Perhaps it is because I have moved a lot in the past ten years. I moved from one place to another, from one geography to another. Besides that, I’m not only interested in physical space but also in mental space: how do you situate yourself in an environment? My interest in psychology made me want to explore how a space influences one’s psychology, the way one thinks, how one’s brain functions, etc. For example, I’m fascinated by the fact that when we walk, our experience of gravity changes completely in relation to when we sit or lie down. Or by the way in which our experience of the world changes while we grow up: as foetuses, we float in the womb of our mother, a warm, enclosed space filled with water. As babies, we get to know the world mainly lying down, slowly discovering how to sit up and see things differently. As kids, everything around us feels huge, until we are fully grown and things are more or less at our level. I’ve always been fascinated by these kinds of observations.

What place does architecture have in your practice, Dareen?

DA : My work dives into the inner self and the environment around it. I’m very interested in exploring relationships between sculpture and cinema – that makes architecture come into my work by default, but it is never the aim.

What I find most fascinating are the natural elements and matter – natural and industrial matter: how we relate to them, how we construct culture through them and how we reflect on them.

The father’s architectural designs are never realized and exude a utopian way of thinking. In the piece, there is an overall tension between being in a concrete, physical space and wanting to escape into another, more mental kind of space. What does the possibility of a mental space outside of reality mean to you both?

RJ: The designs by the architect are indeed not realized, they are not even realistic. They were a product of his obsessive desire for hiding and safety. Some of the inspiration for the design for me came from a Japanese architectural movement called Metabolism, an avant-garde movement formed in Japan in the beginning of the 1960s. They developed utopian concepts to answer architectural and urban challenges that post-war Japanese society faced at the time. One of their projects was a building in the ocean, free from any nationality.

Most of these architectural designs that I found were not realized, they only exist on paper. There is something very interesting about that because it is full of potential and not fixed in reality. For me, a mental space is a fluid space: something I wouldn't be able to grasp or identify.

DA: What is important to me when I create any work is to have a mental space to create a state of absorption. I need to be fully at one with what I am thinking and doing. That is perhaps what hiding could mean to me.

What would be your ideal architectural space to hide in?

DA: The ideal architectural space to hide in will exist only when science has developed the biological capability to change our skin’s material, texture or colour, depending on the circumstances.

RJ: For me this space will not be an actual building but a concept, and I am still searching for it.

A conversation with Dareen Abbas & Rimah Jabr, by Esther Severi & Eva Decaesstecker (Kaaitheater)