IT IS STILL RAINING ON FRANCISCO CAMACHO

Dance critic Inês Nadais in conversation with Meg Stuart

Dance critic Inês Nadais spoke to Meg Stuart, before last year’s reprisal of BLESSED in Porto and Lisbon.

Source: Inês Nadais in Público, 16/06/2017

Translation: Helen Simpson

Ten years after the premiere of BLESSED – a solo created especially for the Portuguese dancer Francisco Camacho – Meg Stuart is bringing the show back to Porto and Lisbon. The piece has aged well, she says; the world not so much. When Meg Stuart first saw the rain fall on the pocket-sized model that scenographer Doris Dziersk showed her, which immediately became the most auspicious beginnings of a new piece, it did not carry the cataclysmic violence of the environmental apocalypse that it is now impossible to miss in BLESSED. But even that rain falling in droplets from a small sprinkler was enough to destroy an entire world in minutes, Doris assured her. Doris had the idea of working with cardboard and water after spending time in Latin America, with its eternally precarious, eternally temporary cities, which we all believe to be unreal until we actually go there.

Meg Stuart believed in her. At first, the apocalyptic devastation that Hurricane Katrina caused in New Orleans, where the American choreographer and dancer was born and raised, and which she thought should have been the most solid and indestructible city of call, had also seemed like a hallucination. It was 2006 (BLESSED had its debut in Ghent in March the following year) and it was impossible not to associate the proposed installation on the table in front of her with the shock of that disaster, seen in real life, during those unimaginable days in late August 2005.

‘At that time, I kept thinking about how absurd it was that all the assistance in the days after Katrina failed – the whole structure failed – and about the extreme experience of losing everything from one moment to the next. You have your wonderful world, or at least your world, and then suddenly that falls apart… How do you react? How do you live with that? How do you keep your faith? What do you believe in? I couldn’t get those questions out of my head,’ she tells Público from Berlin, days before bringing the solo performance back to Portugal.

But at the same time, she goes on, other things were coming into her head: ‘The favelas in Brazil; the homeless people on the streets in our cities; the disaster tourism that leads people to want to visit the most devastated places in Haiti; or… Most of all, I was intrigued by people’s resistance. I wanted to understand how we keep going in spite of everything; what it is that keeps us going.’

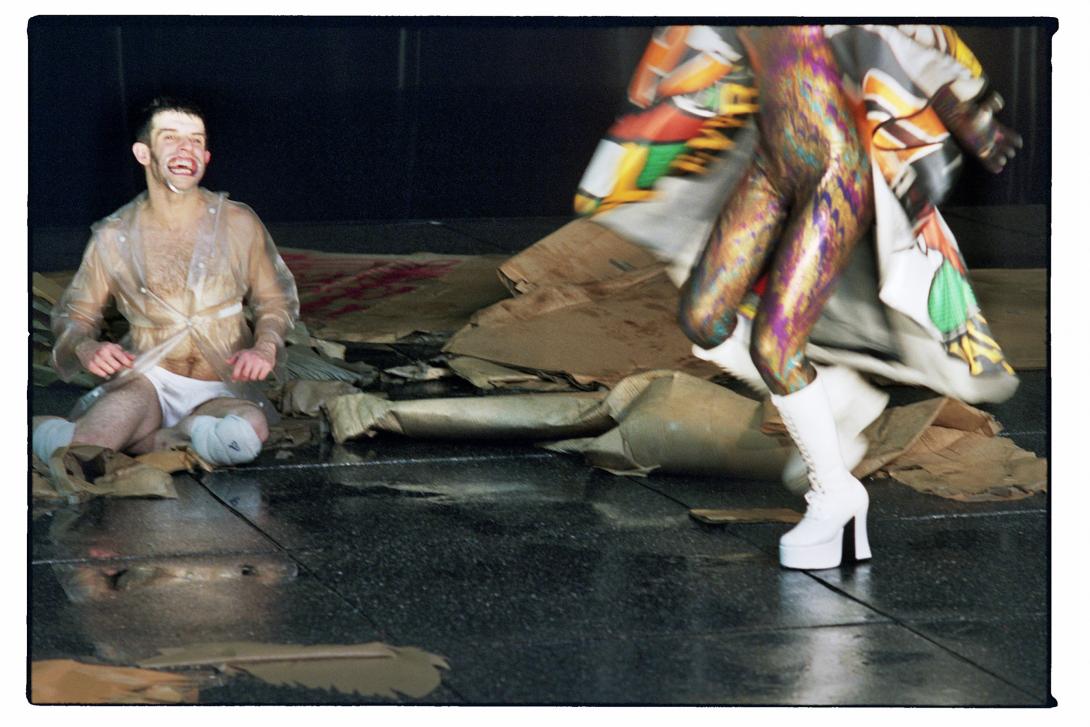

During those days, there was something else she couldn’t get out of her head: the body of Francisco Camacho – one of the most exceptional she had encountered in the late 80s, just before she became a choreographer. In fact, she has seen few like it to this day. She couldn’t imagine the rain, which she wanted to cascade down on stage, falling on anyone in the world as well as it would fall on him; there was no one capable of inhabiting, with such mystery and authenticity – holding on as though there were no tomorrow – the little cardboard paradise (a hut, a swan and a palm tree) that we see collapsing before our eyes like something out of a disaster movie, over the course of 70 minutes.

‘That was a long time ago… But I still remember being in New York in those early years, to dance and teach, and someone – I don’t know who – telling me that there was a very special, strong dancer that I had to meet. He did a few things with me in the studio and then, when I went to Leuven to do my first piece, Disfigure Study (1991), I wanted him to be one of the performers. The way he moved was exceptionally intelligent, very precise and very well crafted; he moved with incredible presence, and he still does,’ the choreographer tells Público. Since then, they have been in constant contact (Camacho was her assistant on UNTIL OUR HEARTS STOP, which premiered in 2015), but it wasn’t until 2006 that Meg Stuart fi nally got her hands on the perfect setting for a solo by Francisco Camacho. BLESSED was the piece that she created especially for him and it is, perhaps, even more enjoyable seeing him perform it now than it was ten years ago.

ENDURING

To recap: a man, a hut, a swan, a palm tree and the unrelenting rain that still falls on them ten years on. A hurricane named Katrina and a president called Donald Trump (who would have this to say on Twitter about the Paris Agreement: ‘Covfefe’). ‘The world is worse than ever; we are not doing well at all. In 2007, the phenomenon of global warming was still just beginning. Suddenly, it seems that everything has got alarmingly more precarious,’ says Meg Stuart. But she didn’t want to put the weight of that on BLESSED, which actually has a heartening and overtly religious title (if we see a god moving out there, it is not a hallucination). It seems to say: fear not, water is a saviour; it washes away the sins of the world.

Before salvation, however, an entire little universe will undergo harsh punishment: the hut, the swan, the palm tree and the only inhabitant of this lost paradise. ‘I wanted to see how Francisco would handle the heavy adversity of that rain over time. The piece was being written as we were looking at how he danced before and after the water, and how much time it would all last – his resistance, and the resistance of the materials,’ Meg Stuart tells us. Francisco Camacho’s body endured – we all endure. ‘As a performer, Francisco doesn’t allow much of himself to be seen. On stage, he has a very strong presence, but one that does not seem to be associated with an ego. That is why it is easy for us to project ourselves onto him but difficult to grasp him completely. He doesn’t throw his distinctiveness out to the public. Quite the opposite: he lets the public step into that world; into that fantasy.’

He was the ideal soloist for a choreographer with a preference for ‘multifocal’ group pieces in which a lot happens to a lot of people at the same time, or, indeed, for her own solo performances. ‘With Francisco you can work with small, subtle, precise movements; he essentially lets the movement move through him.’ None of that has been lost ten years on. ‘It’s all still there and it’s still just as strong… I think seeing him do this piece now that he is ten years older makes it more real and emotive; more poignant. For me, it’s lovely to watch a mature performer in action and witness a life experience play out on stage. Politically, I think it is important for dance not to be a place just for twenty-somethings. It is important for me to be able to continue dancing too.’

At the age of 52, something keeps her going.