Conference of the Absent

Lees meer over Conference of the Absent

More information on tickets, playdates the credits of the performance can be found here.

REPRESENTATIONS WANTED

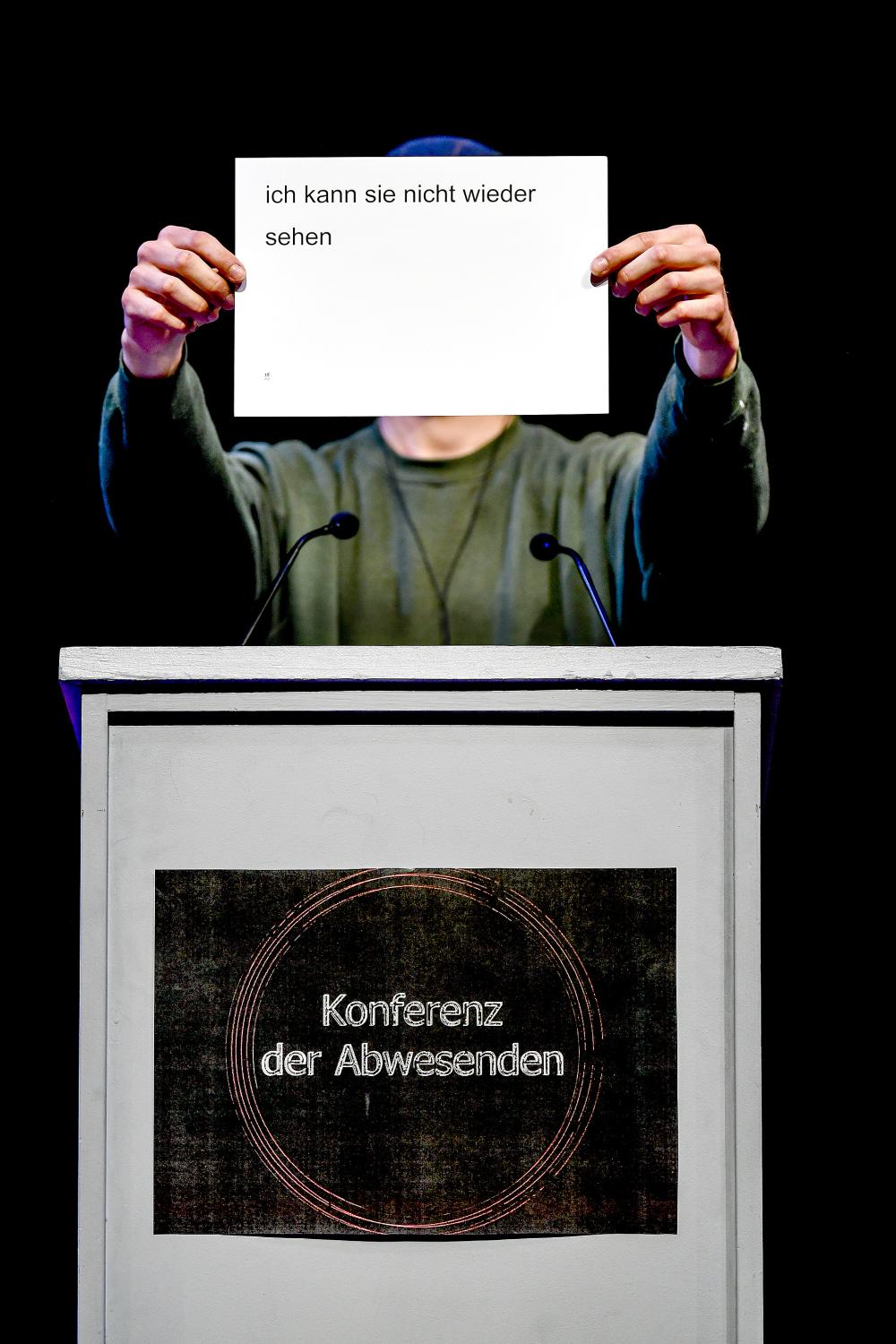

An internationally staffed conference which no one travels to, and which – please, not again – is not supposed to simply take place digitally. How should that work? Here is a proposal: The speakers simply hand over their presenta- tions to those who are there and who do not have to travel from afar: to citizens from the very city in which this conference of the absent takes place. Is there a more suitable space for such an experimental arrangement than the theater? The directing and writing team Rimini Protokoll, together with the audience, dare exactly this experiment.

Everything it needs: a kind of play manual, the prepared conference presen- tations and the technical support on site. And, of course, audience members. The advantage, by the way: This conference can be attended several times, is a bit different each time, is relatively environmentally friendly, and can take place in a wide variety of locations around the world – even at the same time. In this way, the diverse biographies, stories, thoughts and positions of those who themselves are not there and cannot be, find new bodies every evening. And at the same time absence itself is the theme: What are different forms of absence? Where and when are we absent? What does absence do to us? When is absence a curse and when perhaps a blessing? The experts at this conference have all had their own experiences.

With the beginning of the conference of the absent, a double game emerges that draws circles: Those present take on the role of those absent, and those absent thereby become present. This conference generates interference, as Werner Friedrichs observes in his contribution to this program booklet, it blurs boundaries between stories, identities and bodies and in doing so – this much seems certain – will repeatedly come up to their limits as well as its own. But after months of reduced presence of bodies worldwide and the total ab- sence of spectators from the theater, it also radically breaks through this sad state of affairs: it hands over the theater space – along with the stage – to its audience.

Unlike usual plays, no one determines the cast for this one. The question of who (re-)presents whom and what, remains not least a game of chance each time. Who will represent whom this evening, in this performance and in this place? The creation of contingent difference, the suddenly possible perceptibi- lity of differences and the abstraction of commonalities begins anew with each performance.

And even more happens: We look to the stage, to a person from our midst, to hear from them a story which is not theirs, but which they adopt playfully for just a moment. But how is our perception of what is being said influenced by the person who is speaking – their appearance, their voice, their perfor- mance? And how does our perception of a person change by what is being said? And what does representation itself, lending one‘s own voice and presence, that ‘letting–someone–else–speak–through–you’, actually do to the represen- tatives? – You will have to try it for yourself. Any volunteers?

REMOTE PRESENCE

On the absence or presence of the common by Werner Friedrichs

Dr. Werner Friedrichs is Academic Director at the Otto-Friedrich-University of Bamberg. He leads and accompanies (in cooperation with the Federal Agency for Civic Education i.a.) numerous projects at the intersection between aesthetic and civic education. The following text gives an insight into the results of a participatory observation of the rehearsal process for the conference of the absent.

From Con-ferring to Inter-fering

At conferences, points of view, opinions and thoughts are gathered. [Con-fer - con = together, shared]. Conferences are held to bring a common (as a concern, question or problem) to presence. However, they are thwarted by the logic of the re-presentation of the absent(ees). The experts‘ presentations are about insights they have acquired elsewhere: in the laboratory, in the space of logical laws or in the empirical field of investigation. Business representatives stand up for the interests of their industry, their companys or their contractual partners. Members of parliament and envoys represent the interests of voters, minorities or those affected. The contributions (the compiled) thereby oriented by an order of presentation:

I stand here for something else. I have gathered something for this. What is at stake in each case is not present, but in a different place: in the transcendent sphere of scientific truths, a production site outsourced to the point of invisi- bility, or an affected distant region. How could it be organized that the con- ference participants do not only show each other professional presentations, styled graphics and position papers? How could the absent contexts, working conditions or glocal entanglements be gathered in such a way that they become present at the site of the conference? How could what is represented be made present in such a way that the scattered diversities, places and needs inter- weave, interpenetrate and create a common thread? How can the con-ference become an inter-ference? In other words: Do experts really have to travel thousands of air miles to sit across from each other in conference centers, to point out connections in seminar rooms, to complain about watery coffee at high tables, or to affirm intentions in large circles? If a co-existential moment of different perspectives, needs and concerns is to be realized in a con-ference, don‘t the representatives, speakers, agents and even sometimes the witnesses get in the way? Step aside – we want to realize something shared here!

In the conference of the absent these questions are given space.

One Million stories of democratic existence. How to get together?

Thus, the conference of the absent touches the central, democratic problem: the problem of procuration, of representation. How can it be possible, in mass societies with scattered differences, oppositions, dependencies and needs, to envision and maintain the democratic cohesiveness of a social bond? How can the hybrid entanglements be made palpable in such a way that they enable and promote thinking and acting in solidarity? A question on whose answer depends nothing less than the planetary well-being of humanity. The mass extinction of species, the increasing social inequalities or the steadily rising numbers of refugees requires acting together in solidarity.

It is crucial for democracies to make the indeterminable many, the multitude, the co-existence „present-able“ (Lorey 2020) in conferring, in assembling. Because democracy is a „mode of living together“ (ibid., 14). The precise meaning of democracy – in its composition of demos and krátos – is the empowerment to do things together. „The ability to do things is not one that everyone makes use of to the same degree, but it refers to the many, diverse individuals who, in their social heterogeneity, shape common life together“ (ibid., 36). This understanding of democracy was already obscured in ancient polemics. The original claim to always envision the indeterminable many (make it present-able) and thus keep it alive as the driving force of action was perver- ted by the technique of representation: Now the many were to be represented in the unity of the whole. In this way, democracy was inscribed with a burden- some legacy that it has never been able to fulfill: to represent the many – the absent – in a unity. This distorted, imagined juxtaposition of the many and the one often leads to paradoxes and blockades. The hybrid multitude, howe- ver, eludes the distinction between unity and multiplicity. The many absences simply cannot be gathered in conferences, parliaments and consultations of representatives, experts and witnesses.

The incomprehensible horizon (the uncountable) of common action, the way of living together, only comes to light in entanglements, enmeshments and intersecting narratives. It becomes palpable only in the overlaps and inter- ferences of the narratives. The presence of particular persons does not help. Sometimes it even proves to be a hindrance. For the presence of the experts distracts from absent entanglements and stories. And they are exactly what it is about: those singular stories in which we have to involve ourselves, envision together. In this way, the idea of an „audience democracy“ (Manin 2007), in which the many spectators follow the one (representative) deliberation, recedes into the background. In the conference of the absent, the spectators embody the entanglements and narratives from the multitude, without the latter being absorbed by the presence of designated experts, representatives, or witnesses. Thus, in the conference of the absent, a present-able moment of multitude, of the uncountable, is made audible.

1) The term interference is used in physics to describe a superposition of waves. One of the best-known manifestations of interference patterns is provided by the double-slit experiment: waves strike permeable apertures, creating superpositions with changing amplitudes (see Barad 2015, i.a.). Just as the stories in the Conference of the Absent visualize new interactions with fluctuating intensities and entanglements in their embodiments by the speakers. The mass of individual destinies becomes common stories. They entangle us, connect us.

RE⎪PRESENCE

New presences in the European cultural scene.

A conversation with Joachim Bernauer (Director Goethe-Institut Rom/Country Director Italy), Francisco Frazão (Artistic Director Teatro do Bairro Alto Lisbon), Joachim Klement (Artistic Director Staatsschauspiel Dresden), Chloé Siganos (Director Performing Arts Centre Pompidou Paris) and Barbara Van Lindt (Artistic and Administrative Coordination Kaaitheater Brussels). Moderated by Imanuel Schipper and Lüder Wilcke.

What have cultural institutions learned from the pandemic, which new perspectives have emerged?

Chloé Siganos (CS) I think the relationship with artists is different now, it has become more democratic. We are more connected as people than before. It‘s nice to see that creativity and the way we think about distance is very diffe- rent now. We have learned to create with less mobility but with more dialogue.

Joachim Klement (JK) A good experience is that creativity cannot be stopped by a pandemic. In Dresden, we produced an entire festival as a hybrid format, and in the last few months I have seen many productions that were created in the course of the pandemic situation, that would not have existed in that way before.

What does this situation mean for cultural mobility?

Joachim Bernauer (JB) At the Goethe Institut, we have successfully ex- perimented with interactive formats. And we had more students than the year before. The digital allows us to reach people who we would otherwise not be able to reach geographically. We also talked more with our colleagues in Munich, Paris, or around the world. There is more exchange with artists and among cultural workers and less travel.

Barbara Van Lindt (BVL) It is the pandemic that determines our program. The cultural sector, and especially the arts sector, has gone through an identity crisis due to the pandemic: we are witnessing how a virus destroys all curatorial concepts and narratives. It is hard but also liberating. What is emerging instead is a different commitment to the local art scene. In addition, the cultural sector has had to subordinate itself to the government. They decide what you can and cannot do. We were obedient for more than a year. In the second lockdown the government offered no prospects. So we decided on our own to close until the end of March since we didn‘t want to stay in this dependency, but to create a period that would be a fertile ground for our team to reflect, experiment and work on topics.

Francisco Frazão (FF) I was thinking about this quote from jurassic park, that life always finds a way. I think art also always finds a way, theater finds a way, artists find a way. That‘s what we experienced last year. We had a curfew on the weekends until 1pm. So we did theater in the morning, and the audience came. If they only let us do theater at noon, then we do theater at noon. So there‘s this persistence to explore presence as something precious, not just digitally.

In the conference of the absent, there‘s a line at the end of the play where it turns into the Conference of the Present - in German that is just one letter difference. The person on stage begins to repre- sent a position without knowing who’s. So they say „I“ before kno- wing what this „I“ is.

JK This work poses a central question to the theater: who represents whom? For example, can an old white man from Dresden speak for a young woman from East Africa? This is one of the burning debates of our time.

BVL „Speaking on behalf of.“ I think that‘s where there is potentially moral friction: that there is perhaps as much of a gap between the person speaking on behalf of someone and what is being said.

FF The conference deals with this debate in a playful way, showing us that we can think both presences at the same time, have them in our minds: the original and its „translation“. This is a playful challenge for the audience, a non-dogmatic idea that will materialize on stage. In addition, some of the absent speakers are not absent by choice, but simply cannot be there because it is impossible for them. So it‘s not only a nice concept, but thematically it‘s also a real necessity.

JB We are now used to thinking digitally. But this is about physical repre- sentation. Right now we can watch hours of streamed theater – which is nice and interesting. But we‘re missing the physical approach. This is put on stage in the conference of the absent in a very radical way: The „real“ person portrayed is not there, instead there is a physical person on stage.

CS And it also holds another question: What is real? And what makes me believe it‘s real. Are these facts – or fakes?

BVL I think in a polarized world full of Fake News, etc., it‘s important to make the audience aware of these gaps.

JK This production does something else: getting people involved in a situati- on without knowing beforehand what will happen to them. And it seems that they trust the game and the theater. And that‘s something I find very positive. It’s not normal in daily life to trust the unknown.

The concept of conference of the absent is that the play travels, but if possible no one else travels, just the play: the idea and the tech- nical instructions. That brings us to the topic of sustainability. How much has your work already been influenced by this?

JB Rimini Protokoll asked: How can we tour without leaving such a large carbon footprint? This is just as true for the Goethe-Institut. During the pandemic we are discovering that we really feel good when we travel less. This idea of telepresence is more than just a playful concept. We will have a lot of fun with it on performance evenings, but to answer the question of how physical presence can be realized without a lot of travel, we would have to think much more creatively. That‘s why Rimini Protokoll and the Goethe-Institut will continue to work on this with other agents from theater and civil society, and will also hold an academy of the absent in four European cities.

JK Cultural institutions have a responsibility to make relevant themes of the future visible. We are therefore working on many topics related to sustainabi- lity. But not only on the stages – we also have to live what we talk about in our institutions. And you can see that for many people in the company it is a real need to be involved in this.

FF There are many ways to make sustainability a part of our daily lives. This production takes this issue very seriously. But we in Portugal are on the periphery of Europe, so we don‘t have the luxury of being able to be in five different countries within two hours on a train. Sustainability is in a way a luxury for some, and it is very dangerous to give up this exchange that travel provides. The danger is that we revert to a kind of digital Middle Ages, where we have digital exchanges but we don‘t leave our walled cities. The fact is that not traveling is not an option for all artists. Jérôme Bel or Rimini Protokoll might be able to present their work without traveling. Because they are known worldwide. But newcomers are not invited by anyone if their work has not been seen yet. Maybe we are in a transitional phase and in twenty years there will be much less travel. We still need to protect the cultural importance of actual travel - and thus co-presence.

BVL Yes, you are right. I think the mentioned artists can benefit from their decades of traveling the world. But Mexican theater-maker Lázaro Gabino Rodríguez points out that his livelihood depends on European festivals co-producing his work. So, to call now for a global travel ban is not that simple.

CS It‘s helpful and good to have a choice. It may take decades to make the connection between what we used to live and what we want to live in the future. We are children of Europe – it would be hard for me to say we will not travel anymore. Also, and especially for political reasons. Because Europe is increasingly confronted with extremism, protectionism and similar issues. Cultural institutions – and our generation – therefore also have an obligation to show young people how to deal with foreignness. We have a choice now. It‘s a political statement, I think.