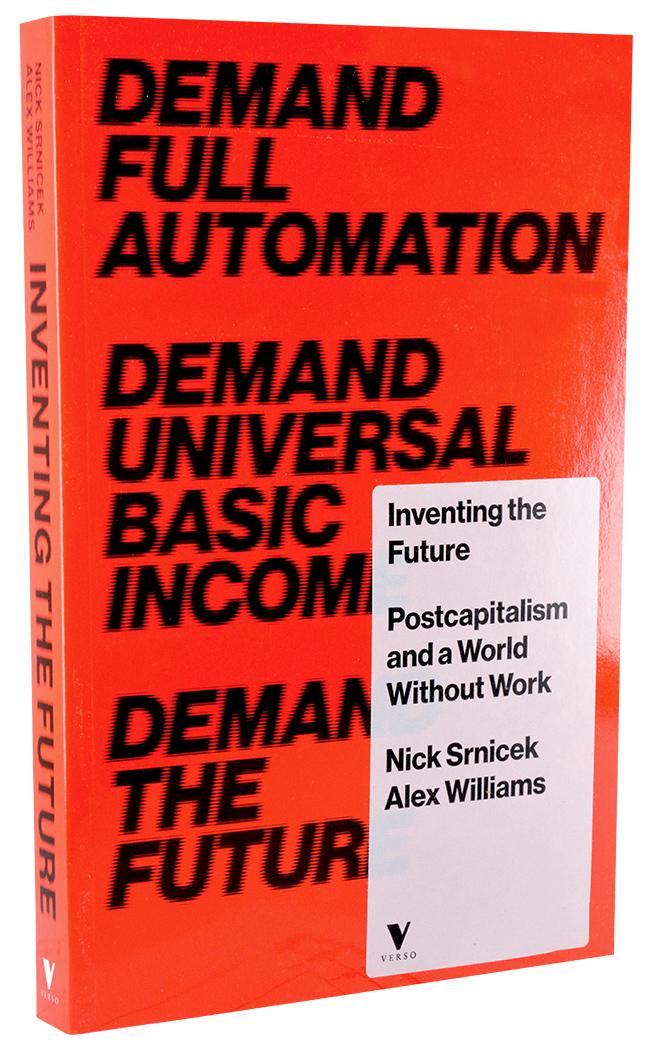

Inventing the Future. Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

Where did the future go? For much of the twentieth century, the future held sway over our dreams. On the horizons of the political left a vast assortment of emancipatory visions gathered, often springing from the conjunction of popular political power and the liberating potential of technology. From predictions of new worlds of leisure, to Soviet-era cosmic communism, to afro-futurist celebrations of the synthetic and diasporic nature of black culture, to post-gender dreams of radical feminism, the popular imagination of the left envisaged societies vastly superior to anything we dream of today.[i] Through popular political control of new technologies, we would collectively transform our world for the better.

Today, on one level, these dreams appear closer than ever. The technological infrastructure of the twenty-first century is producing the resources by which a very different political and economic system could be achieved. Machines are accomplishing tasks that were unimaginable a decade ago. The internet and social media are giving a voice to billions who previously went unheard, bringing global participative democracy closer than ever to existence. Open-source designs, copyleft creativity, and 3D printing all portend a world where the scarcity of many products might be overcome. New forms of computer simulation could rejuvenate economic planning and give us the ability to direct economies rationally in unprecedented ways. The newest wave of automation is creating the possibility for huge swathes of boring and demeaning work to be permanently eliminated. Clean energy technologies make possible virtually limitless and environmentally sustainable forms of power production. And new medical technologies not only enable a longer, healthier life, but also make possible new experiments with gender and sexual identity. Many of the classic demands of the left – for less work, for an end to scarcity, for economic democracy, for the production of socially useful goods, and for the liberation of humanity – are materially more achievable than at any other point in history.

Yet, for all the glossy sheen of our technological era, we remain bound by an old and obsolete set of social relations. We continue to work long hours, commuting further, to perform tasks that feel increasingly meaningless. Our jobs have become more insecure, our pay has stagnated, and our debt has become overwhelming. We struggle to make ends meet, to put food on the table, to pay the rent or mortgage, and as we shuffle from job to job, we reminisce about pensions, and struggle to find affordable childcare. Automation renders us unemployed and stagnant wages devastate the middle class, while corporate profits surge to new heights. The glimmers of a better future are trampled and forgotten under the pressures of an increasingly precarious and demanding world. And each day, we return to work as normal: exhausted, anxious, stressed and frustrated.

At a planetary level, things appear even more ominous. The breakdown of the global climate continues unabated, and the ongoing fallout from the economic crisis has led governments to embrace the paralysing death-spiral of austerity. Buffeted by imperceptible and abstract powers, we feel incapable of evading or controlling the tidal pulsions of economic, social and environmental forces. But how are we to change this? All around us, it seems that the political systems, movements and processes that dominated the last hundred years are no longer able to bring about genuinely transformative change. Instead, they have forced us onto an endless treadmill of misery. Electoral democracy lies in remarkable disrepair. Centre-left political parties have been hollowed out and sapped of any popular mandate. Their corpses stumble on as vehicles for careerist ambitions. Radical political movements bloom promisingly, but are quickly snuffed out by exhaustion and repression. Organised labour has seen its power systematically taken apart, leaving it sclerotic and incapable of anything more than feeble resistance. Yet, in the face of these calamities, today’s politics remains stubbornly beset by a lack of new ideas. Neoliberalism has held sway for decades, and social democracy exists largely as an object of nostalgia. As crises gather force and speed, politics withers and retreats. In this paralysis of the political imaginary, the future has been cancelled.[ii]

This book is about how we got here, and where we might go next. Using an idea we call ‘folk politics’, we offer a diagnosis of how and why we lost the capacity to build a better future. Under the sway of folk-political thinking, the most recent cycle of struggles – from anti-globalisation to anti-war to Occupy Wall Street – has involved the fetishisation of local spaces, immediate actions, transient gestures, and particularisms of all kinds. Rather than undertake the difficult labour of expanding and consolidating gains, this form of politics has focused on building bunkers to resist the encroachments of global neoliberalism. In so doing, it has become a politics of defence, incapable of articulating or building a new world. For any movement that struggles to escape neoliberalism and build something better, these folk-political approaches are insufficient. In their place, this book sets out an alternative politics – one that seeks to take back control over our future and to foster the ambition for a world more modern than capitalism will allow. The utopian potentials inherent in twenty-first century technology cannot remain bound to a parochial capitalist imagination; they must be liberated by an ambitious left alternative. Neoliberalism has failed, social democracy is impossible, and only an alternative vision can bring about universal prosperity and emancipation. Articulating and achieving this better world is the fundamental task of the left today.

– Nick Srnicek & Alex Williams

[i] John Maynard Keynes, ‘Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren’, in Essays in Persuasion (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1963); George Young, The Russian Cosmists: The Esoteric Futurism of Nikolai Fedorov and His Followers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); Mark Dery, ‘Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose’, in Mark Dery, ed., Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994); Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (New York: Morrow, 1970).

[ii] For exemplars of this stance, see Franco Berardi, After the Future (Edinburgh: AK, 2011); T. J. Clark, ‘For a Left with No Future’, New Left Review II/74 (March–April 2012); Fernando Coronil, ‘The Future in Question: History and Utopia in Latin America (1989–2010)’, in Craig Calhoun and Georgi Derluguian, eds, Business as Usual: The Roots of the Global Financial Meltdown (New York: New York University Press, 2011). Or, in the words of one popular recent essay: ‘The future has no future’.: The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009), p. 23.